Archive for the ‘welfare’ Category

Conservative framing of welfare

Jan 22, 2015 – With each example seen in the media (and not just in the rightwing tabloids) it’s tempting to see conservative framing of welfare as simply crass, vicious and stupid. But that doesn’t help us understand why demonisation of benefits recipients seems popular with large sections of the public (witness the popularity of the Benefits Street style TV shows and the rise of UKIP, etc). A cognitive frames approach helps us to get a better insight into the phenomenon…

Jan 22, 2015 – With each example seen in the media (and not just in the rightwing tabloids) it’s tempting to see conservative framing of welfare as simply crass, vicious and stupid. But that doesn’t help us understand why demonisation of benefits recipients seems popular with large sections of the public (witness the popularity of the Benefits Street style TV shows and the rise of UKIP, etc). A cognitive frames approach helps us to get a better insight into the phenomenon…

The differences between “conservative” and “progressive” (or “liberal”) views on welfare have little to with fact and logic. It’s more about opposing metaphorical framing on morality. This framing underlies much of the “social” policy of the right.

1. Conservative view of social welfare:

Welfare seen as essentially “immoral” because:

- It’s viewed as encouraging “dependence” on the government, and so is against the morality of self-reliance & self-discipline.

- It’s not given to everyone, so it introduces competitive unfairness, an interference with the “free market”, and hence with the “fair” pursuit of self-interest (part of the morality of reward and punishment).

- Since it’s paid for by tax, it “takes” money from someone who has earned it, and gives it to someone who hasn’t (against the morality of rewarding self-reliant, self-disciplined people).

Note the particular moral emphasis here: self-reliance, self-discipline, reward and punishment. George Lakoff has documented at length how these values are central to conservative framing (eg in his books, Whose Freedom? and Moral Politics). Moral differences don’t just concern different ideas about “good” vs “bad” – they’re about conflicting hierarchies of values. Liberal/progressive views hold “empathy”, “care”, etc, as primary in moral terms, with self-discipline and self-reliance secondary in moral importance. The inverse is true for conservative (or what Lakoff calls “strict father”) morality.

This doesn’t imply crude either/or reductionism or simplistic stereotyping of people. Different value-hierarchies may apply for a given individual depending on the domain she/he is conceptualisng. For example, some people describe themselves as socially liberal but economically conservative.

Rightwing strategy (via think-tanks & conservative media) has been to repeatedly use the metaphorical language of “strictness” on domains which may have been traditionally framed more in terms of looking after others – ie caring. The economic value-hierarchies of the businessperson thus gradually replace a moral scheme in which notions such as “social security” and “safety net” represented primary values. This entails a moral shift, a change in what’s regarded as normal, acceptable “common sense” (and also, according to some cognitive scientists, an accompanying physical change in our brains).

To quote Lakoff’s Moral Politics:

The basis of the classification of successful businessmen as model citizens is very deep, as we have seen. It is the principle of the Morality of Reward and Punishment, which is at the heart of Strict Father morality. To place restrictions on that principle is to strike at the heart of conservative ethics and the conservative way of life. Placing restrictions on moral people who are engaged in moral activities is immoral. (Chapter 12)

Welfare, government regulation, etc, are thus seen as immoral interferences in a moral system of rewarding “success” in a competitive world. This framing encompasses, in obvious ways, the system of “free market” capitalism. For example, in the latter, the successful pursuit of self-interest in a competitive world is seen as a moral good since it benefits all via the “invisible hand” of the market. In both cases do-gooders are viewed as interfering with what is right – their “helpfulness” is seen as something which makes people dependent rather than self-disciplined. It’s also seen as an interference in the market optimisation of the benefits of self-interest.

Under this moral frame, cuts in welfare (etc) are not just seen as a temporary measure of “austerity” (eg until the economy recovers) – they’re seen as a moral imperative for all time, since the alternative is viewed as fundamentally immoral.

2. Conservative view of corporate welfare:

But what about corporate welfare? Given the above reasoning, shouldn’t conservatives view that, also, as immoral according to this framing?

Corporate welfare not (immediately) seen as immoral because:

- Those receiving it are pre-conceptualised as self-reliant and self-disciplined in the entrenched iconography of the heroic, hard-working, successful “wealth creator”. Under the conservative moral accounting metaphor, they are seen as deserving.

- The comparison between corporate welfare and social welfare thus doesn’t work on most conservatives (at least not without years of reframing), because the heroes and demons in the conservative worldview are based on “deep” cultural metaphors reflecting the primary morality of self-discipline and self-reliance. This takes the form of: “Why shouldn’t the best people be rewarded – their success demonstrates their self-discipline”, etc.

For a more in-depth look at moral-political framing systems, please see our Essentials of Framing.

Antiwork – a modest proposal

Oct 15, 2014 – Antiwork is a new project I’m working on. The aim is to radically reframe “work” and “leisure” – to provide a moral alternative to the obsession with toil.

Oct 15, 2014 – Antiwork is a new project I’m working on. The aim is to radically reframe “work” and “leisure” – to provide a moral alternative to the obsession with toil.

Currently, the rightwing message-machine is winning the battle on work. We’re all supposed to work harder, longer, further into old age, for smaller reward – and be grateful. Some of us are even supposed to work without any pay (workfare), because it’s supposedly good for our “character” and “helps” us to “integrate”. And, of course, we’re to feel deeply ashamed if we’re not working.

The parts of the political left that don’t simply echo this conservative line (Labour Party leaders seem to be the worst offenders) counter with facts and figures. For example, the fact that most people living in poverty already have jobs. And although revealing the facts is necessary, it’s not sufficient. That’s the lesson we learn from framing: frames generally trump facts, especially when they’re deeply entrenched after decades of repetition.

Contributoria

To gauge wider interest in a project like Antiwork, I’ve set out a proposal on Contributoria. The idea is that people back ideas they like with blocks of points (which you get a load of, free, when you join – or at least I did; I think the idea is to eventually make it partly, and optionally, paid-subscription based. The backed ideas get modesty paid).

So, please have a look at my Antiwork proposal, and if you like it, please back it. If there’s enough interest, I’ll not only write the proposed Contributoria article, I’ll also start “work” on the antiwork.org website I’ve created. – Many thanks. [Update – it’s now been backed, and will apear in the December 2014 issue of Contibutoria].

Tabloid stereotypes – typifying classes by worst-cases

Sept 19, 2014 –Today’s Daily Express headline is a particularly nasty example of an irresponsible tabloid practice. Most people would probably (and rightly) think of it as demonisation of a class of people – by constant publication of nightmare cases whose attributes are in no way typical of the class (“migrants”, “benefit claimants”, etc) assigned by the newspaper.

Sept 19, 2014 –Today’s Daily Express headline is a particularly nasty example of an irresponsible tabloid practice. Most people would probably (and rightly) think of it as demonisation of a class of people – by constant publication of nightmare cases whose attributes are in no way typical of the class (“migrants”, “benefit claimants”, etc) assigned by the newspaper.

Apologists for the Express might argue that the headline is factually correct (assuming the details have been reported correctly). But the point is how “facts” and “news” about sensational single cases can be framed in a way that distorts probability judgments, warps logic and incites hatred/fear regarding the class of people referred to.

Prototype Theory: distorting our judgments

Prototype Theory, in cognitive science, looks at the internal structure of categories/classes, and how single class members can stand for the class itself. It offers a useful explanation of what’s going on here (ie how the Express is fucking with our heads, precisely).

Our minds create various kinds of prototype for a given category/class. For example, a typical case, an ideal case and a nightmare case. We tend to use the “typical case” prototype in our inferences about what we consider “normal” (eg statistically, probabilistically) for a category, or class, of people.

Problems arise with something called a “salient exemplar” (a well-known case that stands out for us, for various reasons – including sensationalist media coverage. The tabloids are full of them). The salient exemplar tends to distort our probability judgments about a given class of people if it’s conflated with, or affects our perceptions of, the “typical case”. This can happen quickly, and without much conscious awareness – eg as a result of the repeated media coverage (of the salient exemplar), we have “reflex” associations and responses to the “migrant” frame.

The Express (and it’s not just the Express) knows it would get into trouble with a “KILLER BLACK”, “KILLER GAY” or “KILLER JEW” headline. But it knows it can get away with “KILLER MIGRANT”, just as it knows that it can get away with portraying the class of “welfare recipients” in terms of the “vile” “cheat” salient exemplar. The examples are endless – see my Curious repeating headlines in the Daily Express for a selection).

It isn’t new, of course. Lakoff (in The Political Mind) discusses the uproar that started in 1976, when Ronald Reagan referred to a “Welfare Queen” who had supposedly received $150,000 in government handouts and was driving a “Welfare Cadillac”. As it turned out, nobody could find this person – it appeared to be a made-up stereotype. As Lakoff puts it, “Reagan made the invented Welfare Queen into a salient exemplar, and used the example in discourse as if it were the typical case.” (The Political Mind, p160)

Misleading Vividness fallacy

I mentioned, above, how sensationalist tabloid framing warps logic regarding classes of people. There’s a fallacy in logic known as “Misleading Vividness“, eg the belief that the occurrence of a particularly vivid event (eg a terrorist bombing) makes such events more likely, despite statistical evidence indicating otherwise. Misleading Vividness has strong psychological effects because of a cognitive heuristic called the availability heuristic. There’s a lot of material already available on cognitive heuristics (as a result of the popularity of the work of Daniel Kahneman and others). I think it would be a fruitful area of research to combine this field with that studied by Lakoff et al, particularly with emphasis on media coverage and its effects. In the words of Nassim Taleb (quoted by New Scientist some time ago), media coverage is “destroying our probabilistic mapping of the world”.

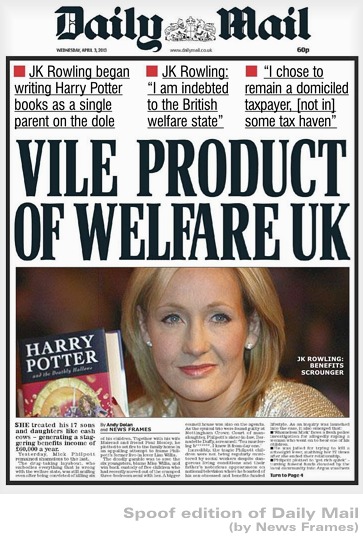

A Daily Mail front page you won’t see…

April 8, 2013 – JK Rowling should perhaps be given a Nobel Prize for getting a generation of kids to read books. As if that wasn’t enough, she’s generated endless amounts of tax revenue. How was this phenomenon nurtured? By a little time and space on the dole.

April 8, 2013 – JK Rowling should perhaps be given a Nobel Prize for getting a generation of kids to read books. As if that wasn’t enough, she’s generated endless amounts of tax revenue. How was this phenomenon nurtured? By a little time and space on the dole.

You’d be surprised how many successful people developed their craft on the dole. In a way, most successful corporations also require a long period on the dole. Do you think Boeing and Microsoft would have achieved commercial success without decades of state-funded research and development in aerospace and computing?

Any true wealth-generating activity requires periods of “social nurturing” which aren’t profitable. They’re not self-funding in the short term; they are dependent. (We realise this for children – we call it “education”. The money spent on it is regarded as social investment).

“Investment” (in human beings) was also one of the ideas – along with “safety net” – behind “social security”. The welfare state was created in the forties, in a post-war economy which was nowhere near as wealthy as now (imagine: computer technology didn’t exist).

But, for decades, the rightwing press, “free market” think-tanks, politicians and pundits (not just of the right) have wanted you to think differently about social security. They want you to think of “welfare” as an unnecessary nuisance which costs more than everything else combined.

To that end, a simple set of claims, accompanied by a certain type of framing, is relentlessly pushed into our brains by newspaper front pages and TV and internet screens. It has two main components:

- Vastly exaggerate the real cost of “welfare” and falsely portray it as “spiralling out of control” (how this is done is explained here and here). Misleadingly include things like pensions in the total cost when you’re talking about unemployment. (This partly explains why people believe unemployment accounts for 41% of the “welfare” bill, when it accounts for only 3% of the total).

- Appeal to the worst aspects of social psychology by repeatedly associating a stereotype (the “benefits scrounger/cheat”) with the concept of “welfare”. One doesn’t have to be a prison psychologist to understand how anger and frustration are channeled towards those perceived as lower in the pecking order: “the scum”. (According to a recent poll, people believe the welfare fraud rate is 27%, whereas the government estimates it as 0.7%).

It’s a potently malign cocktail. When imbibed repeatedly, there’s little defense against its effects. Even those who depend on benefits come to view benefits recipients in a harshly negative light (see Fern Brady’s article for examples). Those politicians who aren’t naturally aligned with rightwing ideology go on the defensive – they talk about “being tough” and “full employment“. It just reinforces the anti-welfare framing.

The strangely puritanical – and deeply irrational – obsession with “jobs”, “hard-working families”, etc, at a time in history when greater leisure for all is more than a utopian promise (due to the maturation of labour-saving technology, etc) seems an integral part of the conservative framing – which is perhaps why many on the “left” find it difficult to provide counter-narratives.

But that would require another article. For now I’ll leave you with a short video explaining Basic Income – a fast-spreading idea which is highly relevant to the above. (Guardian columnist George Monbiot recently championed Basic Income as a “big idea” to unite the left).

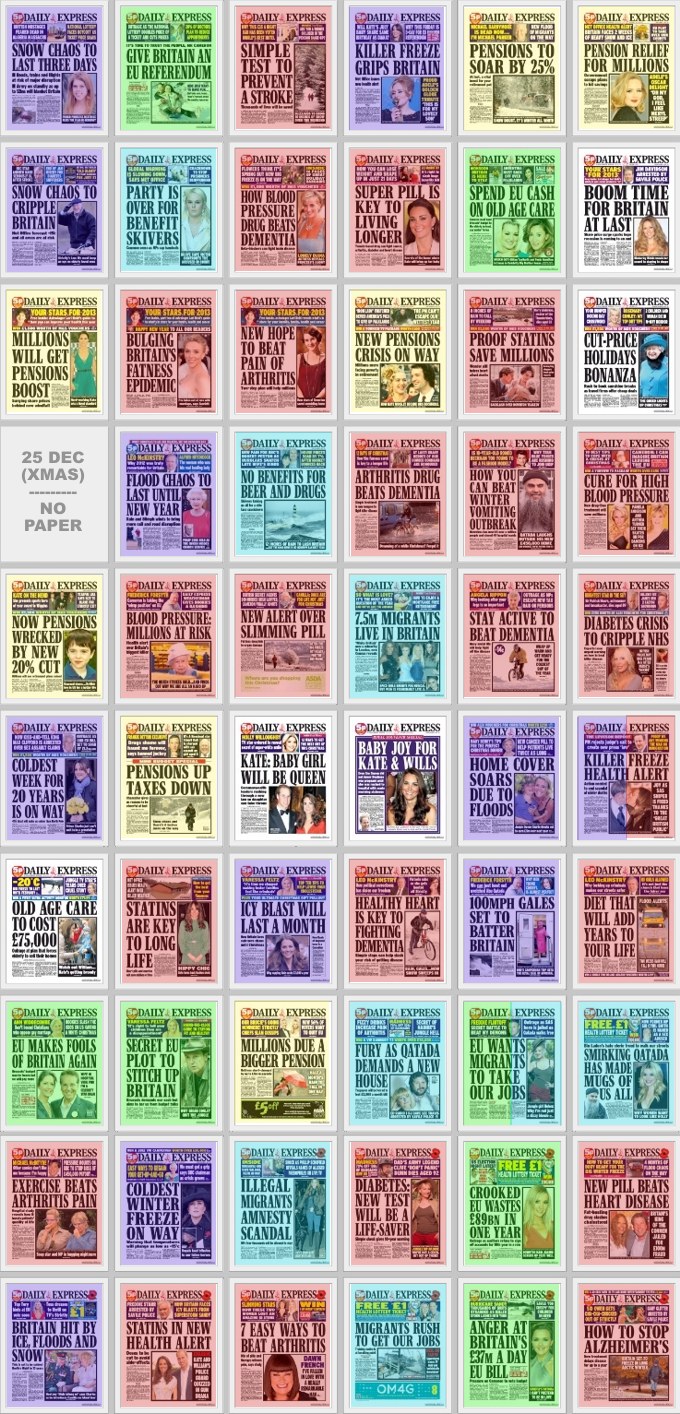

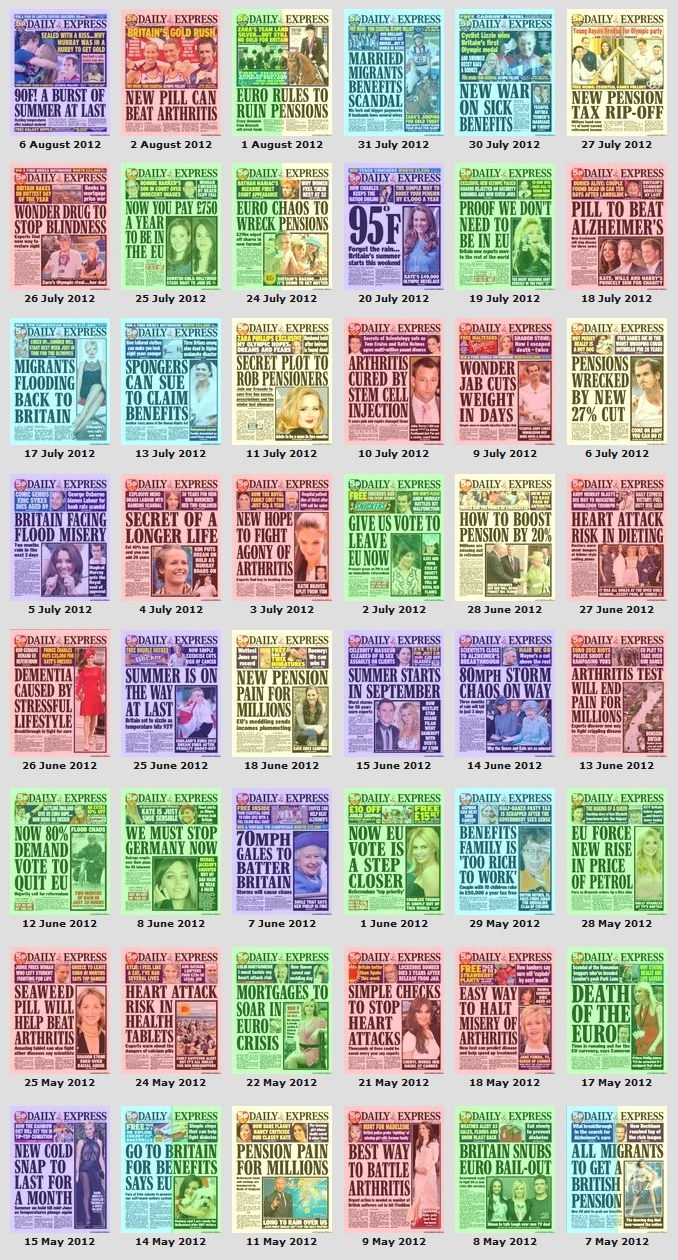

Curious repeating headlines in the Daily Express

Jan 24, 2013 – You’ve probably noticed the Daily Express headlines which feature the weather or some health-related story. It seems that most Express headlines fall into one of these categories:

Jan 24, 2013 – You’ve probably noticed the Daily Express headlines which feature the weather or some health-related story. It seems that most Express headlines fall into one of these categories:

1. Weather/floods

2. Health/illness

3. The EU/Euro

4. Pensions

5. “Migrants”, benefits, “skivers”

Exceptions seem uncommon. Okay, you get the occasional “royals” story, and there was a time when house-price rises/falls could have been added to the list. See for yourself, using the compilations of front pages, below (which I’ve colour-coded to match the above categories).

Occasionally, two of the topics are combined in one headline (see example, above left – “ALL MIGRANTS TO GET A BRITISH PENSION”).

The first collection of front pages shows every Daily Express from 18 January 2013 (top left) back to 29 October 2012 (bottom right), with all exceptions shown (uncoloured):

The latest circulation figures show the Express selling many more copies than the Times, Guardian and Independent (roughly the same number as the Telegraph, and fewer than the Sun and Daily Mail).

The next compilation of Express front pages covers the period from early August 2012 (top left) back to May 2012 (bottom right) – it’s not a complete list, and excludes some exceptions as well as other examples which conform to the above topics:

UPDATE:

Several months after I posted the above article, Press Gazette ran a similar piece titled: ‘Groundhog day: Why Daily Express front pages may leave readers with a sense of deja vu’ (August 7, 2013). It has a different selection of examples of Daily Express front pages than mine (more on the health and weather themes, and some from the period when house prices was a constant headline subject). Here’s the link to it.

Poverty framing – discussion with JRF’s Chris Goulden

Dec 6, 2012 – Every news story requires a frame, and stories about poverty tend to reflect the politicians’ hackneyed narrative about “getting people back to work” – even though in-work poverty is rising, and even though “joblessness” seems low on the list of factors contributing to the big financial meltdown.

Dec 6, 2012 – Every news story requires a frame, and stories about poverty tend to reflect the politicians’ hackneyed narrative about “getting people back to work” – even though in-work poverty is rising, and even though “joblessness” seems low on the list of factors contributing to the big financial meltdown.

Over the years, I’ve found research from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) useful in countering dubious claims (eg from press/pundits) about UK poverty.

How does a group such as JRF address issues which are as much about moral framing as they’re about statistics? Chris Goulden (head of JRF’s poverty team) kindly agreed to discuss poverty framing with me by email…

………………………………….

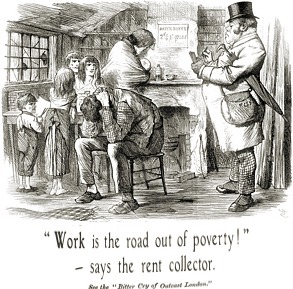

•News Frames: You tweeted that “Work IS the best route out of poverty – half the time”, with a link to a JRF piece of the same title. I replied: “More precisely, ‘having an adequate income’ is the best route out of poverty”.

My intention was to contrast two different poverty “frames” – one focusing on the individual’s “responsibility” (direct causation); the other on social distribution of income (systemic causation). These tend to correlate, respectively, with conservative and progressive moral frames (according to George Lakoff et al).

You mention that it’s a cliché to say “work is the best route out of poverty”. I regard it also as a strong expression of the ‘conservative’ frame which has dominated thinking about work/poverty for decades (this frame/worldview is evangelised by the “self-made man”, industrialist Mr Bounderby, in Dickens’s novel Hard Times, for example).

You mention that it’s a cliché to say “work is the best route out of poverty”. I regard it also as a strong expression of the ‘conservative’ frame which has dominated thinking about work/poverty for decades (this frame/worldview is evangelised by the “self-made man”, industrialist Mr Bounderby, in Dickens’s novel Hard Times, for example).

The figures reported by your JRF piece are very interesting, and I thought they could have been framed in a very different way. Do you (and your JRF colleagues) normally consider framing, or do you regard your material as neutral presentations of findings, etc?

……………………………………….

•Chris Goulden: Negative attitudes among the public, in politics and in the media towards people experiencing poverty is a key barrier. I agree that a different way of framing poverty is needed if there is to be more support for initiatives to reduce it.

•Chris Goulden: Negative attitudes among the public, in politics and in the media towards people experiencing poverty is a key barrier. I agree that a different way of framing poverty is needed if there is to be more support for initiatives to reduce it.

But I don’t think what you call the progressive, distributive, systemic etc. frame necessarily helps. Or at least, simply presenting poverty as an issue beyond the control of individuals experiencing it is not persuasive. I believe there is, and needs to be, a third way (sorry) / synthesis between structural and individualised causes of poverty that is neither solely blaming the individual nor structurally-deterministic. Ruth Lister sets this out well in her book, Poverty (2004).

The role of science, research and evidence is interesting in this context yet also challenging. We and the researchers we work with are not often as explicit as we should be our underlying values and assumptions. This applies as much in natural as in social science. A common and more effective / “truthful” frame for the production of evidence and the discussion of its implications for poverty would be extremely useful.

I’m not sure what precedents there are for reframing issues in this way that could be drawn on however?

……………………………………

•News Frames: I think the ‘Frame Semantics’ literature does have much to contribute, but first I’d better clarify my terms to avoid misunderstandings.

•News Frames: I think the ‘Frame Semantics’ literature does have much to contribute, but first I’d better clarify my terms to avoid misunderstandings.

By “progressive”/”systemic” I don’t mean “beyond the control of individuals”. To me, it seems undeniable that poverty in modern society is a matter of systemic causation. At its simplest: the individual controls some factors but not others (availability of income, costs of housing, etc). So, it seems clear that we should use frames of “systemic causation”. Yet the newspaper headlines have, for decades, presented an extreme form of “direct causation” (eg that the “workshy” are to blame).

I think it’s precisely this latter frame which leads to the “negative attitudes” that you mention. And it’s not just the tabloid newspapers which feed into this. For example, “work is the route out of poverty” is an expression of the same metaphorical frame as blaming the “workshy”.

Lakoff et al have shown how, across many complex issues (from climate to war to welfare), conservative moral frames tend to use the “direct causation” metaphors (eg “Bush toppled Saddam and freed the Iraqis”). So much political debate appears to have followed this kind of direct-cause metaphorical mode, and for so long, that we usually don’t even notice it operating. (I think this is particularly the case with the issue of work/income/poverty).

But the “progressive”/”systemic” alternative isn’t at the other end of a linear scale from the “conservative”/”direct-causation”. They are just two very different modes of thought which we all have “instantiated in the neural system of our brains”. In fact, the notion of a linear political scale (eg left-right) with extremes at the ends, and “moderates” in the middle, is itself a misleading metaphor, according to the cognitive scientists. Or as Lakoff says, there aren’t really any moderates. That’s another debate, of course, but it possibly has a bearing on your point about a “third way”?

•Chris Goulden: Ok, I think we basically agree then. But by framing it as ‘systemic’ or ‘progressive’ (and I’m not sure those two are synonymous), you are implying it is beyond the control of individuals, in the same way that ‘individualised’, ‘regressive’ or ‘conservative’ imply it is only the individual actor who counts. If all parties could agree it was both structure and agency, then we could focus debate on where the balance lies and implications for policy and practice. At present, there is just division and a debate about what’s different not the commonalities of view.

•Chris Goulden: Ok, I think we basically agree then. But by framing it as ‘systemic’ or ‘progressive’ (and I’m not sure those two are synonymous), you are implying it is beyond the control of individuals, in the same way that ‘individualised’, ‘regressive’ or ‘conservative’ imply it is only the individual actor who counts. If all parties could agree it was both structure and agency, then we could focus debate on where the balance lies and implications for policy and practice. At present, there is just division and a debate about what’s different not the commonalities of view.

And then there is the issue of the causative route – you say “the frame leads to the negative attitudes” but, in part at least, the negative attitudes lead to the frame. Which came first?

Regarding the issue of the use of cause as a metaphor, I agree that’s a general problem. The way we all talk is based on thousands of underlying assumptions and theories about the world that are more or less plausible or supported by scientific method or layers of personal experience. I don’t see how this is just a conservative moral frame. What’s the alternative? Socialist chaos theory? 🙂

However, the biggest issue remains – leaving aside what would be a better frame for poverty in this country for a moment – how do frames change and how do people who want to instigate those changes best go about it? That’s what I am really struggling with. Simply saying, as we often do in JRF reports, that there are bigger forces at play – the nature of jobs available, the cost of housing – doesn’t make people believe it and change their opinions.

•News Frames: If you think “systemic” framing implies a denial of individual “control” or “agency” (as factors), then I can see you’d have problems using it on poverty. I just hope you don’t have a “society made me do it” caricature in mind. (By the way, I don’t think “progressive” is synonymous with “systemic” – but the frames tend to correlate).

•News Frames: If you think “systemic” framing implies a denial of individual “control” or “agency” (as factors), then I can see you’d have problems using it on poverty. I just hope you don’t have a “society made me do it” caricature in mind. (By the way, I don’t think “progressive” is synonymous with “systemic” – but the frames tend to correlate).

I’m talking about multiple, complex causation misleadingly reduced, via metaphor, to single, direct causation (eg “hard work leads to prosperity”) – whereas you’re talking in terms of “where the balance lies” between “structure and agency”. Your idea of “balance” appears to make sense (sort of) when you put it in those terms. But if the reality is systemic causation (as it evidently seems to be with UK poverty), then where is the “balance” between appropriate systemic framing and misleading direct-cause framing?

For example, how close are the following statements to your balance point?:

1) “Work IS the best route out of poverty – half the time”. (Title of your recent JRF piece)

2) “We believe that work should be the surest way out of poverty”. (Living Wage Foundation)

You ask why I lay the blame on conservative moral framing in particular. This comes mainly from my reading of Lakoff’s cognitive-linguistic analysis. Here’s a quote from a Lakoff article (2009) which puts this into accessible language:

“Conservatives tend to think in terms of direct causation. The overwhelming moral value of individual, not social, responsibility requires that causation be local and direct. For each individual to be entirely responsible for the consequences of his or her actions, those actions must be the direct causes of those consequences. If systemic causation is real, then the most fundamental of conservative moral—and economic—values is fallacious.

“Global ecology and global economics are prime examples of systemic causation. Global warming is fundamentally a system phenomenon. That is why the very idea threatens conservative thinking. And the global economic collapse is also systemic in nature. That is at the heart of the death of the conservative principle of the laissez-faire free market, where individual short-term self-interest was supposed to be natural, moral, and the best for everybody. The reality of systemic causation has left conservatism without any real ideas to address global warming and the global economic crisis.”

I also think Lakoff answers (much better than I could) your question on how to instigate changes in framing. He’s written books specifically on this subject. ‘Don’t think of an Elephant‘ is a good starting point, if you haven’t already read it.

Incidentally, I assume that your chicken-and-egg question (“Which came first?” – the negative attitudes or the frame?) wasn’t serious, as the context was decades of headlines blaming the “workshy”, etc. But if you are serious, I’ll return to it.

•Chris Goulden: So, maybe my joke about socialist chaos theory was actually closer to the truth than I thought? I think it’s an important point to unpick about whether “systemic” is correlated with progressive or not. I don’t see why they should be. “Systemic” is an objective description of how we think reality works. “Progressive” is a value system.

•Chris Goulden: So, maybe my joke about socialist chaos theory was actually closer to the truth than I thought? I think it’s an important point to unpick about whether “systemic” is correlated with progressive or not. I don’t see why they should be. “Systemic” is an objective description of how we think reality works. “Progressive” is a value system.

But this does go to the heart of the methods of social science, and indeed of natural science. I’ve no doubt that reality is systemic and that simple direct causes are uncommon if not non-existent in terms of explaining human behaviour. We, I hope, are taking a systemic approach in our new programme that is aiming to develop an anti-poverty strategy for the UK. It aims to show what it would be like to live in, and what it would take to reach, a UK without high levels of poverty.

I think the statement ‘work is the route out of poverty’ by itself doesn’t imply structural or individual causes. Or even non-systemic ones. We always argue that it’s not just the fault of individuals and that all our opportunities are restricted by structural circumstances. If you tried to maintain a systemic approach to all discussions about policy and practice then I fear you wouldn’t ever be able to say anything. We need heuristics not exact models of reality.

What might a systemic description of poverty and its solutions look like to you and would this frame by itself help to reduce negative attitudes? I think negative public attitudes have complex causes and are not just the direct result of decades of headlines (and there is a strong current going in the other direction). Aren’t you reverting to a ‘morally conservative/direct causation’ frame there?

•News Frames: On your last point: I think you’ve misread – or misunderstood – my remarks about “negative attitudes” (towards the poor). I wrote: “it’s not just the tabloid newspapers which feed into this”. I referred to a culturally dominant frame (on work/poverty) which has complex historic causes – eg: I mentioned Dickens’s Hard Times, which contains a virtual taxonomy of this metaphorical framing.

•News Frames: On your last point: I think you’ve misread – or misunderstood – my remarks about “negative attitudes” (towards the poor). I wrote: “it’s not just the tabloid newspapers which feed into this”. I referred to a culturally dominant frame (on work/poverty) which has complex historic causes – eg: I mentioned Dickens’s Hard Times, which contains a virtual taxonomy of this metaphorical framing.

The frame manifests as negative attitudes to the poor (among other things) – the frame being the cognitive underpinning of the attitude. Negative attitudes towards the poor are generally inseparable from the frame of poverty as moral failure of the individual. Decades of newspaper headlines (among other things) reinforce this moral framing. I see no single, direct cause here.

I’ve already provided pointers to Professor Lakoff’s work. I think it would yield diminishing returns to revisit (again) the point about “progressive”/”systemic” correlations – at least while you’re unfamiliar with the body of research I’m referencing. However, I’ll briefly address your question on “systemic” approaches to poverty.

One obvious example is the frame of poverty as social harm. Responsible society has a moral obligation to protect people from harm. We already have the metaphor of a “safety net” – as well as numerous examples, from other domains, of public funding of public safety. Note how this contrasts with the (‘conservative’) frame of poverty as moral failure of the individual. In extreme cases of the latter, the individual’s poverty isn’t  regarded as harm, but as tough medicine, or as an incentive for market discipline, etc – and the notion of a safety net (such as welfare) is regarded as immoral, since it makes people “weak and dependent” (in this moral scheme – for more details, see my ‘Essentials of framing’).

regarded as harm, but as tough medicine, or as an incentive for market discipline, etc – and the notion of a safety net (such as welfare) is regarded as immoral, since it makes people “weak and dependent” (in this moral scheme – for more details, see my ‘Essentials of framing’).

Given that you’re looking for “a different way of framing poverty” – and given that JRF seems to take a broadly “progressive” stance – I’d have thought Lakoff’s work would be of enormous practical benefit to you. If there’s a more substantial body of work on social-political framing out there, I haven’t seen it – and I’ve certainly looked.

But I’ll leave it at that, as overselling these things can be a kiss of death.

•Chris Goulden: I think it might be helpful to try to sum up where we agree and where we disagree (or are yet to agree)?

Here’s what I think anyway – let me know if you agree with what I think we agree on 🙂

- Systemic understanding and causes are better depictions of reality than direct causes

- The dominant frame around poverty in the UK is negative and a barrier to progress on effective action to reduce poverty

- A more positive framing would be helpful but it is very difficult to change this but we should try; and we should watch out for repeating negative framing in JRF’s treatment of poverty and related issues

- I need to read some Lakoff

Here’s where I don’t think we agree

- Systemic understanding naturally goes together with a ‘progressive’ approach (I don’t see how that is logically possible)

- A ‘agency within structure’ framing could be more helpful than a systemic one (although I still don’t quite get that – see point 4 above)

- Individual actions, behaviours and attitudes still matter – obviously that doesn’t just apply to people experiencing poverty, also employers, politicians, research funders etc. By trying to remove victim blaming, you risk denying agency, free choice etc.

- Within a systemic frame, direct causes still have a place (otherwise we wouldn’t be able to understand anything (“it’s all too systemic”))

•News Frames: Only one point stands out, to me, as a real disagreement. This is where you write: “By trying to remove victim blaming, you risk denying agency, free choice etc” (point 3). I certainly disagree with this. I don’t think it follows at all – and the absurd implication is that since we shouldn’t deny poverty victims free choice, we must therefore blame them for their poverty.

•News Frames: Only one point stands out, to me, as a real disagreement. This is where you write: “By trying to remove victim blaming, you risk denying agency, free choice etc” (point 3). I certainly disagree with this. I don’t think it follows at all – and the absurd implication is that since we shouldn’t deny poverty victims free choice, we must therefore blame them for their poverty.

Here’s an alternative (“systemic-causation”) frame: Poverty as a result of multiple, complex causes, which may include the actions of the individual experiencing poverty (among other interrelated factors). Simple enough. It avoids “victim blaming” (single, direct cause); it avoids presenting work as “the route” out of poverty (single, direct cause) – but it doesn’t deny individual agency/free-choice.

Note: I offered to give Chris the final word, but he said he was happy to leave that last reply of mine as the final thing. Many thanks to him for taking the time to discuss this issue. I recommend both his regular JRF blog and his Twitter account (a good source of links to poverty studies and news articles, etc). – BD

The ever-popular “war on workshy” frame

Oct 8, 2012 – Today’s Express headline concerns the “WAR ON WORKSHY”. I first became aware of this “war” back in 1998, when the following headlines screamed at me (on March 27th, 1998):

Oct 8, 2012 – Today’s Express headline concerns the “WAR ON WORKSHY”. I first became aware of this “war” back in 1998, when the following headlines screamed at me (on March 27th, 1998):

“WELFARE WAR ON WORKSHY” (Daily Mail)

“BLAIR IN WELFARE WAR ON THE IDLE” (Daily Telegraph)

“SHAKE-UP IN WELFARE HITS THE WORKSHY” (The Times)

“THOU SHALT NOT SHIRK” (The Express)

I was unemployed at the time, and I took it personally – it seemed like a war on me. It also struck me as being political and journalistic bovine excreta. The same media had just reported the lowest official unemployed count for 18 years (given as 1,383,800 in The Daily Telegraph, 19/3/98). Government figures showed that only 5% of welfare expenditure went on the unemployed, including benefit fraud. (The percentage is pretty much the same today – see my earlier post).

As Larry Elliott (Guardian’s economics editor) put it at the time:

“..ministers should stop conniving in the fallacy that the welfare state is in a terminal crisis when it palpably is not…What is not legitimate is to pretend that welfare is a luxury Britain cannot afford”.

(Larry Elliott, The Guardian, 19/1/98)

It’s all déjà vu for me. We were in a “terrible crisis” then, and we’re in a “terrible crisis” now. And we’re encouraged to think about this crisis – repeatedly – in terms of a war between “hard-working families” and “workshy scroungers”. Or, as today’s Express puts it:

Senior Tories believe the move will be popular with millions of hard-working families who are fed up with workshy scroungers ripping off the benefits system. (Express, October 8, 2012)

This frame tends to exclude the thoughts: 1) that large numbers of “hard-working families” are themselves dependent on various benefits (since the market often doesn’t pay a survival/living wage), and 2) that many of those “hard-working families” will eventually find themselves unemployed (at which point they land in the “workshy scrounger” category – until they can find another job).

After decades of relentless tabloid attacks on the unemployed, the cited Tories are probably right – in a sense – about the “popularity” of the proposed welfare cuts. Because the “real” war is in the framing, and the Framing Wars are currently being won by the rightwing press (which, as noted recently by George Monbiot, gets much of its editorial content direct from neoliberal thinktanks). We see an indication of the success of this framing (in shaping people’s thinking) from the 2012 British Social Attitudes survey, which reports that:

62% agree that unemployment benefits are too high and discourage work, more than double the proportion who thought this in 1991 (27%)

So, don’t think about the trillion pounds spent bailing out the banks, or the $21 trillion stashed in tax havens by the tax-avoiding super-rich, etc – those are separate, different news compartments. Focus your anger on the unemployed people. The frames in your head tell you they deserve it.

Alternative headlines:

• ‘WAR ON YOUNG & OLD & VULNERABLE’

• ‘WAR IS PEACE, WORK IS MANDATORY’

• ‘BANKS BAILED OUT BY SLAVE LABOUR’

• ‘ANOTHER SUCCESSFUL ANGER-REDIRECT HEADLINE’

◊ Read more about the metaphorical framing of welfare here and here,

– and more about the framing of work here & here.

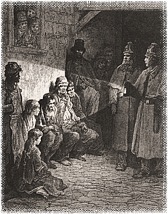

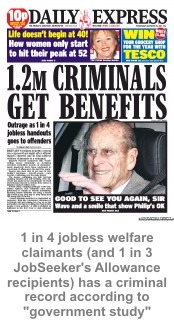

Welfare “criminals”

Dec 28, 2011 – Today’s Express front page reports that 33% of JobSeeker’s Allowance recipients have “records of offending” in the last five years. The Sun and Telegraph also covered this story under the blunt headings: “One in three on dole is a criminal”; “Third of unemployed are convicted criminals”.

Dec 28, 2011 – Today’s Express front page reports that 33% of JobSeeker’s Allowance recipients have “records of offending” in the last five years. The Sun and Telegraph also covered this story under the blunt headings: “One in three on dole is a criminal”; “Third of unemployed are convicted criminals”.

The figures reportedly come from a “data sharing agreement between the Department for Work and Pensions and the Ministry of Justice”, but at the time of writing, neither DWP nor MoJ appear to have this finding on their websites. [See update, below*]

Predictably, the rightwing TaxPayers’ Alliance (so-called) is quoted by the Express. Robert Oxley (TPA campaign manager) says: “The minority who split their days between claiming benefits and getting rich from the proceeds of crime are giving those who fall on hard times a bad name”. Of course, there’s no indication that the crimes involved made anyone “rich” – after all, we’re not talking about Goldman Sachs here.

(For example, poor people receive criminal records for watching TV without a licence. I don’t see anyone getting rich from that “crime”.)

Not that the details matter to the hard-right ideologues at the Express, Telegraph, Sun and TaxPayers’ Alliance. What matters for them is that welfare is framed as “criminal” and immoral. What matters to them is that public anger is directed away from the wealthy beneficiaries of public misery, and towards “criminals” and people receiving benefits. And if the distinction between “criminals” and people receiving benefits is blurred, that’s viewed as a bonus.

* Update – This story has also been covered by the Daily Mail, Mirror, Star, Metro and Times, but the “government study” on which it’s based remains unavailable – which means it’s difficult to check the figures, and to put them into context. One aspect of context is statistical comparison – for example, 1 in 4 US adults has a criminal record (according to Yahoo! News), the same ratio that the Express cites for all out-of-work UK benefits recipients. It would be interesting to see what proportion of Express journalists has a criminal record.

Alternative headlines:

• ‘BENEFITS RECIPIENTS ROUTINELY CRIMINALISED’

• ‘WAR IS PEACE, WORK IS MANDATORY’

• ‘JOBLESS PUNISHED BY SHAME & EARLY DEATH’

This “orthodox” economics reflects Victorian (or earlier) frames and metaphors (eg see economist Paul Ormerod’s work in this regard*). And, going back to Charles Dickens, you can see the whole worldview described (and seemingly subtlely satirised) in his novel

This “orthodox” economics reflects Victorian (or earlier) frames and metaphors (eg see economist Paul Ormerod’s work in this regard*). And, going back to Charles Dickens, you can see the whole worldview described (and seemingly subtlely satirised) in his novel