Archive for the ‘Moral politics’ Category

The strange case of Glenn Greenwald – part 1

This article is also available at medium.com

Guccifer 2.0 – arbiter of “public good”

26 Feb 2020 – In October 2016, Glenn Greenwald had a conversation with Naomi Klein, in which Klein tried to pose a few criticisms of the ways Greenwald and Julian Assange covered the hacked Clinton/Podesta/DNC emails.

Unfortunately, the two media stars address only one of Klein’s criticisms – about privacy protections when hacked material is released without being “curated”. On the other criticism, which Klein frames carefully – possibly to avoid offending Glenn (they seem good friends) – Greenwald doesn’t take the bait, so nothing of much substance is tackled.

Naomi Klein puts her unaddressed criticism in the following terms: the hacked emails were published in ways to “maximize damage” (to the Clinton campaign); we’re not learning a “huge amount” from them – they’re just used to “reinforce” what we already knew about the venal side of campaigning; The hack isn’t non-partisan or ‘information wants to be free’ – it’s a “political weapon”.

Judging from the transcript date, Naomi’s criticisms came days after an article co-written by Greenwald that published hacked Clinton documents received from Guccifer 2.0. Titled “EXCLUSIVE: New Email Leak Reveals Clinton Campaign’s Cozy Press Relationship”, the material here seems relatively weak (the article concedes that “to curry favor with journalists” is “certainly not unique to the Clinton campaign”), but given Greenwald’s standing, the piece served to reinforce the relentlessly negative focus on Clinton during a crucial period in the election run-up.

Guccifer 2.0 was operated by Russian military intelligence according to the 2018 Mueller indictments, although some evidence for this Russian attribution was publicly established months prior to Greenwald’s October 2016 article. After his article, Glenn continued to claim there was “no evidence” of Russian state involvement (although he later reportedly accepted the Mueller indictments as genuine evidence of Russian hacking).

(Tweets from before and after Greenwald’s Guccifer 2.0 sourced piece)

Greenwald also wrote (a few days after his Guccifer 2.0 piece) that “the motive of a source is utterly irrelevant in the decision-making process about whether to publish”. The only relevant question, Glenn asserts, “is whether the public good from publishing outweighs any harm”.

That seems a nice soundbite, but the “public good” of a story’s publication is often precisely the thing that’s contested in regard to the source’s motive – especially with political stories in the run-up to an election! To ignore the motives behind the creation and timing of political stories is, perhaps, to risk turning journalism into a plaything of the powerful. (If I thought Greenwald understood this, I’d conclude he was disingenuous to suggest that Guccifer 2.0’s motives were “irrelevant” to the decision on whether to publish).

Unrelated, but sort of ‘illustrative’ here, I stumbled on a New York Times story (from 2015) about Bernie Sanders’ alleged cozy relations with wealthy donors. Although not entirely comparable to Greenwald’s story about Hillary’s “cozy press relationship”, it seems on a par in some respects. Both stories attack a political candidate, both rely on an anonymous source with dubious motives, and neither story seems particularly important in its own right. Does Glenn comment on the NYT piece? Yes, he does – on the source’s “cowardly” motives. He also retweets a comment about the NYT “abusing” anonymity to “dump” on Sanders:

(Web archive link to Glenn’s tweet and retweet – both dated 12 July 2015.

(Web archive link to Glenn’s tweet and retweet – both dated 12 July 2015.

Greenwald deleted tens of thousands of his pre-2016 tweets, en masse).

After Wikileaks published material from the DNC hack linked to Guccifer 2.0, Julian Assange unequivocally denied that the source was Russian-state associated (on some occasions he merely said there was “no proof” of this, or gave credence instead to the Seth Rich conspiracy hoax). Like Greenwald, Assange played down the relevance of the source, reportedly telling news media that: “it’s what’s in the emails that’s important, not who hacked them”.

The journalistic equivalent of naïve realism is that there exists such a thing as raw, unmediated “news” – as if publishing is a window (whether clear or distorting) onto this objectively pre-existing “news”. This view certainly makes sources’ motives seem less relevant. But news is created and framed by the act of telling (ie publishing) – that’s what distinguishes it from non-news. Wikileaks asked Guccifer 2.0 for hacked material to create a story apparently timed to “engineer discord between the supporters of Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton during the 2016 Democratic National Convention”:-

“if you have anything hillary related we want it in the next tweo [sic] days prefable [sic] because the DNC [Democratic National Convention] is approaching and she will solidify bernie supporters behind her after […] we think trump has only a 25% chance of winning against hillary … so conflict between bernie and hillary is interesting.” (Wikileaks to Guccifer 2.0 – from Mueller indictment)

When Greenwald (with the help of Guccifer 2.0’s hack) co-created the news story about the Clinton campaign’s “cozy press relationship”, his framing was of nefarious political influence on reporting. Central to the story was the source of this influence – namely, Hillary’s PR operation, with its obvious political motives in feeding stories to favoured journalists. Greenwald and his co-author try to make this sound suitably nefarious and newsworthy by using terms such as “plotted”, “manipulating”, “plant”, “induce”, but the hacked documents don’t live up to this framing – to me, they read just like boring, standard bureaucratic campaign documents (see for yourself).

So, Greenwald gives us a story about a source of stories (Hillary’s campaign) and its tactics to “shape coverage to their liking”. But it’s “utterly irrelevant” to the publication of Glenn’s story that his own source (Guccifer 2.0, Russian military intelligence by all accounts/evidence) had a motive to shape news coverage? As people say on social media: rriiiiiiiiiiiiight.

Tweet within tweet within tweet…

Trump-frame reinforcers

A while back, it became clear that my occasional criticism of Greenwald’s output was alienating some of my readers. I hope this post helps to explain why I’m critical of Greenwald, and why I regard his influence on the ‘left’ as a sort of lottery win for projects funded by people on the ‘right’ with an interest in framing debate among burgeoning ‘anti-establishment’ audiences. I’m interested in the analysis of framing, not in speculative conspiracy theories.

The first thing I noticed when I began paying attention to Greenwald’s prolific tweeting was that it seemed to constantly reinforce Trump’s talking points (usually by attacking the same politicians, media and commentators that Trump was attacking, on the same issues, and with more or less the same timing). This was in the run-up to the 2016 presidential election, but it continued after Trump was elected.

Perhaps most obviously, Glenn promoted the notion that Trump was less likely (than Clinton) to start wars. This idea had been encouraged by Trump himself, as part of his anti-Hillary platform. Greenwald wrote that Trump had a “non-interventionist mindset”, and encouraged the generalisation of Democrats as being the greater hawks. His colleague at The Intercept, Jeremy Scahill, took a similar line, saying that Trump represents “the best hope we’ve had since 9/11 to actually end some of these forever wars”.

Relevant links: Scahill quote, Guardian piece

Greenwald and Scahill weren’t the only ones who swallowed the ‘war-averse’ version of Trump. It’s notable, and curious, that those who so closely monitored (and fearlessly reported) Obama’s drone-strike militarism seemed to stop paying so much attention when Trump was the one killing thousands. After Trump took office, there was an increase of US troops deployed abroad. Trump escalated every conflict he’s presided over, ramping up bombing in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Somalia and Yemen, increasing civilian deaths (in some cases to record-high levels) while removing civilian protections and reducing accountability. In the year after Trump became president he oversaw more than 10,000 US-led coalition airstrikes in Syria and Iraq, with a 215% rise in civilian deaths. Trump’s drone strikes far exceed Obama’s. US weapon sales to foreign countries have increased under Trump.

None of this should come as a surprise if you paid attention to Trump’s strongman campaign rhetoric on the use of America’s colossal military force (“I would bomb the hell out of them”, “I would bomb the s— out of them. I would just bomb those suckers”,“take out their families”), outside of his rants against the foreign policy of Obama and the liberal interventionism of Hillary Clinton. But if you were focused on the latter – the anti-Democrat diatribes – perhaps you came away with a different story.

When those who viewed Trump as relatively ‘war-averse’ started citing Trump’s firing of John Bolton as support of their view, I felt we’d entered some really weird zone of cognitive dissonance. After all, Trump appointed Bolton in the first place. We’re supposed to think he fired him as a sort of principled stand, after suddenly realising Bolton wasn’t so averse to war after all?

Links: Greenwald tweet via @charliearchy tweet

Less obviously than with the “non-interventionist Trump” view, Glenn sometimes puts forward the notion of Trump as blunt, honest, straight-talking guy (which is something Trump and his people have pushed, no doubt to counter the widespread impression of Trump as habitual liar). Here’s an example: On 17 November 2018, the media reported that Trump was briefed on a CIA report about the killing of journalist Jamal Khashoggi. Greenwald had already commented on this assassination (on a Fox News show), reinforcing typical Fox News messaging about Obama and Washington media elites: “the reason people in Washington suddenly decided that they’re angry about Saudi Arabia is because this time their victim is somebody they ran into in Washington restaurants”.

Trump’s record is worse than Obama’s – as measured by Greenwald’s apparent criteria – when it comes to defending the Saudi regime’s barbarism (Trump also rejected measures intended to prohibit arms sales to the Saudis, and he rejected a bipartisan resolution to end US military involvement in Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen). In fact, Trump’s record on human rights seems shockingly bad across the board – the product of the same shameless, brutal indifference and malice towards “the inferior other” (inhabitants of “shithole countries”, etc) that informs Trump’s whole worldview. So, out of all possible takes on this, what framing does Glenn go with? Well, Trump’s just being more “honest” and “blunt” – we’re seeing his admirable traits:

Link to tweet: just more honest & blunt

It’s not that the Democrats are undeserving of criticism on these issues – it’s that Trump is currently in power, and wielding that power in increasingly brazen authoritarian actions. Greenwald nearly always seems to reframe stories which are rightly Trump-damning as, instead, being about the failing and hypocrisy of “establishment liberals” and “scummy” Washington media. (It reminds me of Frank Luntz’s advice to Republicans to “always blame Washington” – to frame every bad thing as ultimately being the fault of the liberal establishment; to relentlessly repeat that it’s all about elitist D.C. complacency – that was the advice of Luntz, a rightwing spin guru). With occasional exceptions, Glenn’s reframing of controversies in Trump’s relative favour has seemed systematic for around four years.

The tendency hasn’t gone unnoticed by the Trumps:

(Incidentally, the comment from Adam Schiff that Greenwald links to above was from 29 March 2015 [full transcript here], just a few days after the first Yemeni casualties – the full extent of Saudi brutality unfolded over the following years. Cf: the evolution of Glenn’s opinion on hostilities against Iraq – see below)

Of course, the counter-examples shouldn’t be ignored, and this piece by Greenwald stands out as a direct attack on Trump’s escalation of hostilities. It was written after Glenn had been widely ridiculed for his depiction of Trump as “non-interventionist”, and it begins by replaying the shocking catalogue of increased killing under Trump’s presidency. But then it turns into a strange polemic which frames this barbarism in terms of “the clarity of Trump’s intentions regarding the war on terror”. Glenn writes that Trump’s escalation of bloodshed is “exactly what those who described his foreign policy as non-interventionist predicted he would do”.

For months, in 2016, Greenwald had a pinned tweet asking, ‘Is it really necessary to spend next 6 months pointing out that “criticism of Clinton” ≠ “support for Trump”?’ – no doubt to save him the bother of responding to all those who noticed that he seemed overwhelmingly focused on Hillary Clinton and the “lib”/”dem” establishment, while leaving Trump relatively unscathed. (Incidentally, I never noticed anyone arguing that Clinton was undeserving of criticism, or that criticism of her in itself implied support for Trump).

In August 2016, The Intercept’s Robert Mackey noticed a similar thing with Wikileaks: “In recent months, the WikiLeaks Twitter feed has started to look more like the stream of an opposition research firm working mainly to undermine Hillary Clinton than the updates of a non-partisan platform for whistleblowers.”

Both Greenwald and Assange rationalised their constant, relentlessly hostile focus on Clinton’s Democrats (in the 2016 election run-up) by claiming that Trump was already “prevented” from becoming US president. Assange said “Trump would not be permitted to win”. Greenwald said the US media was “preventing him from being elected president”. (After Trump won, Greenwald said the media “played an important role, as well, in ensuring that he could win”).

Greenwald’s style of political framing, with hyperbolic and sweeping denunciations of “liberals”, “Democrats”, “Washington”, NBC and MSNBC (and “liberal media” in general) – and with Hillary Clinton, Obama and the “liberal establishment” typically presented as the greater evils (relative to supposed outsiders such as Trump) – reminds me of so-called ‘alt-right’ framing – the kind of anti-liberal fuck-you message engineered by Steve Bannon and Breitbart (and seen also on 4chan, InfoWars, etc) to appeal to a younger “anti-establishment” audience. (See Joshua Green’s book, Devil’s Bargain, on Bannon’s project to capture this audience. Incidentally, Greenwald praised Breitbart for its “editorial independence”, of all things).

“Democrats are full of hatred and always need to have a heretic to demonize.

They have no ideology, so that’s their fuel.” (Glenn Greenwald, 23 November 2019)

‘Repulsive progressive hypocrisy’ (Title of February 2012 Greenwald article)

“NBC News and MSNBC have essentially merged with the CIA

and intelligence community and thus, use their tactics…

This is who they are. It’s also what the Democratic Party is”

(Glenn Greenwald, 8 July 2018)

“What are Greenwald’s politics, exactly?”

Back in January 2014, The New Republic published an article by historian Sean Wilentz which documented various views espoused by Greenwald, Edward Snowden and Julian Assange that seemed at odds with public portrayals of these men as broadly left/progressive dissidents.

For example, it cited a December 2005 blog post in which Greenwald writes the following:

“Current illegal immigration – whereby unmanageably endless hordes of people pour over the border in numbers far too large to assimilate, and who consequently have no need, motivation or ability to assimilate – renders impossible the preservation of any national identity.” (Glenn Greenwald, 3 December 2005)

“Hordes” of immigrants threatening “national identity”? Not a very progressive outlook – although many of Greenwald’s fans questioned the relevance of these political beliefs to the more recent NSA whistleblower stuff. So what if Greenwald and Snowden once had some rightwing views and hated socialism? Wasn’t this just another attempt to smear them?

Professor Wilentz’s article perhaps makes more sense in hindsight, following Trump’s ascendance to power. Wikileaks, for example, secretly offered to help Trump’s campaign, privately favoured the Republican Party over Clinton’s Democrats, and openly boasted of how influential it had been (via Facebook metrics) on the US election. Greenwald, with over a million followers on Twitter, and regular appearances on Fox News (on which he responds to the anti-liberal emphasis and framing of Tucker Carlson, usually with reinforcement rather than challenge), seems just as influential.

According to Wilentz, Greenwald envisaged uniting rightwing “paleoconservatives and free-market libertarians” with leftwing “anti-imperialists and civil-liberties activists” in a sort of popular revolt against an establishment composed of “mainstream center-left liberals and neoconservatives”.

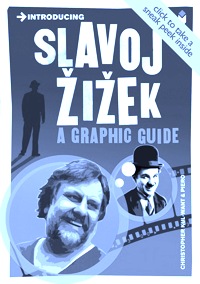

This uniting of heterodox left and right against an odious liberal establishment, in order to shake up the status quo, seems a common enough trope. To the extent that it reframes libs/dems/”centrists” as the greater evil, it reinforces a political worldview of the right. Contrast a view expressed by Noam Chomsky in an interview following the 2016 election. Chomsky had been saying that Trump posed an existential threat, and that the main thing was to stop him. When asked if Slavoj Žižek had a point (that Trump would shake-up the system and be a positive force in undermining the status quo), Chomsky replied:

“Terrible point. It was the same point that people like him said about Hitler in the early thirties. He’ll shake up the system in bad ways… If Clinton had won, she had some progressive programmes. The left could have been organised to keeping her feet to the fire and pushing them through. What it’ll be doing now is trying to protect rights that have been, gains that have been achieved, from being destroyed. That’s completely regressive.” (Chomsky in interview with Mehdi Hasan, November 2016)

Although he often quotes the MIT professor approvingly, Glenn’s output regarding Trump-vs-Democrats seems to consistently push in the opposite direction to Chomsky’s advice. As I’ve noted previously, Glenn tends to frame the MAGA, Brexit, “yellow vests” movements, etc, as popular revolts against the elite establishment status quo, rather than as regressive projects that cynically exploit social discontent.

By the way, nothing controversial is implied here by drawing attention to differences/similarities

in the primary framing and emphasis of influential people with similar/different political personas.

Greenwald’s anti-left views?

In contrast to Greenwald’s recent positive framing of the “yellow vests” protests, etc, here’s his reaction to anti-Bush demonstrations (Latin America, 2005), which he says were “depraved” – he describes the protesters as “truly odious”:-

As is true in U.S., the Latin American socialist agitators who have captured the attention and affection of the American media are as substance-less as they are inconsequential. They are lovers of Fidel Castro. The[y] insist that the source of their severe economic woes is not their collectivist policies or national character, of course, but the evil economic policies of the U.S. (Glenn Greenwald, ‘Unclaimed Territory’ blog, 4th November 2005)

Their “national character” is partly to blame for their economic woes? I won’t speculate on what Greenwald meant by this, but it doesn’t sound good. Meanwhile, Glenn denounces the US media in sweeping fashion (“As usual, the truth is vastly different than what the U.S. media is reporting”) – but it’s a denunciation of the type one usually hears in rightwing circles:

Unsurprisingly, the attention-craving [Hugo] Chavez’s principal ally in these escapades seems to be the American reporters and correspondents reporting on Bush’s trip. They instinctively regurgitate stories of supposedly widespread anti-Bush sentiment based upon nothing but a handful of socialist stragglers defacing public property with anti-war cliches and jobless Latin American hippies gathering for some music, celebrity-gazing and chants. (Glenn Greenwald, ‘Unclaimed Territory’ blog, 4th November 2005)

Greenwald hammers the US media for exaggerating the scale of anti-Bush protests, and for suggesting that the “[Bush] Administration’s policies are flawed because people in other countries dislike Bush”. He writes that the US media are doing this because large-scale anti-Bush rallies are “consistent with their ideology”.

In the same post, Glenn argues that because the September 11th attacks didn’t occur in Latin America, “Latin Americans do not perceive the need to change the Middle East as being as critical and urgent as Americans perceive that need to be.”

Although Greenwald had become critical of Bush by this point, the ‘conservative’ framing/tone remains (on the topic of US national security). The whole post reads to me as if Glenn is implicitly defending Bush’s policy in Iraq against the protests of these “socialist stragglers” (and their friends, the US media), who don’t understand the threat posed by Al Qaeda because they haven’t experienced it for themselves, unlike the good American citizens who support Bush because they understand the dangerous reality he’s fighting. As Greenwald puts it: “It should be axiomatic that the risks posed to American national security will best be understood and appreciated by Americans, not by those in other countries.”

In another blog post, Greenwald writes that the protestors are “hard-core Communists” (his italic emphasis). That’s right: commies!:

“These demonstrators hate the United States because they are genuinely opposed to economic freedom and individual liberty, and they seek to impose the collectivist authoritarianism of Fidel Castro onto the entire Latin American continent. It really is that simple.” (Glenn Greenwald, ‘Unclaimed Territory’ blog, 5th November 2005)

Incidentally, Glenn was nearly forty when he held these views.

Greenwald’s deep moral-political worldview?

As the cognitive linguist, George Lakoff, demonstrated at length in his book, Moral Politics, our political opinions are rooted in complex moral worldviews which we form over the course of our lives, starting in childhood. We each have what he calls a “strict” moral outlook in some areas, and a “nurturant” outlook in others, leading to “conservative”, “rightwing” political opinions in the former and “progressive”, “leftwing” opinions in the latter. (See my extended summary of the Moral Politics thesis).

Lakoff uses the term “biconceptual” to refer to this dual outlook in an individual. When semantic framing of a ‘rightwing’ outlook is constantly repeated, it reinforces that outlook in our biconceptual minds, while neurally inhibiting the progressive outlooks (and vice versa). Our self-identity in any area is often most clearly expressed by what we fight against – someone with a well-established “conservative” moral outlook may be disgusted by, and fight against, liberals and lefties, and vice versa. And contrary to flattering opinions we have about ourselves, we tend not to change our established moral-political outlooks based on our changing evaluations of facts alone.

Having said that, people can radically change – it’s possible that a middle-aged adult with an established ‘conservative’ outlook in important (but not all) areas, and exhibiting a deep dislike of dissident lefties and socialist views, could invert this worldview, together with their own self-identity, in a few years. Maybe. Perhaps in Greenwald’s case you don’t need to make that argument if there is, in fact, no deep reversal of worldview, just a shift in hostile rhetorical targeting away from lefties/socialists, to focus more on establishment/liberals.

Glenn’s explanations of some of his earlier ‘conservative’-sounding views make interesting reading. Here’s how he accounted for his views on illegal immigration (he’d complained in his political blog that “nothing is done” about the “parade of evils” caused by such immigration):

“I had zero readers … there were many uninformed things I believed back then, before I focused on politics full-time – due to uncritically ingesting conventional wisdom, propaganda, etc. … nobody was reading my blog; it was anything but thoughtful, contemplative, and informed, and – like so many things I thought were true then – has nothing to do with what I believe now.” (Glenn Greenwald, 24 April 2011)

I find this unconvincing. By his own account, Glenn wound down his litigation practice in 2005 in order to pursue other things, “including political writing”. He was no “uninformed” youth when he started writing a political blog – he was (to quote Wilentz) “a seasoned 38-year-old New York lawyer”, who had, among other things, represented a white supremacist neo-Nazi leader (a remarkable story). Greenwald’s writings on immigration weren’t just isolated “uncritically ingested” factoids – they expressed an established, conservatively-framed worldview on that particular issue. His opinions and framing on other issues in his blog at this time – eg the anti-socialist views discussed above – consistently express this worldview (although it’s important to note that he had liberal views on other issues – what you might call a “partial progressive” in Lakoff’s terminology).

It also seems irrelevant to his political outlook that “nobody” was reading his blog at the time (this seems a strange point for him to emphasize – and one that’s echoed in his argument that his private support of the Iraq war didn’t really count as support because he had no platform as a writer at the time – see below).

Support of the Iraq War – and later denial

Glenn has often attacked ‘libs’ and ‘dems’ for any support they expressed for George W. Bush’s policy of invading Iraq in 2003. This is also attenuated in posts in which he mocks “Resistance” figures for referring to the Bushes in positive terms generally. In one recent example he sarcastically mocks Nancy Pelosi for making a casually friendly remark about the Bush family (somewhat off-target given that Pelosi was a vocal opponent of the Iraq war and a critic of Bush’s policies).

Greenwald also writes scathingly of the “rehabilitation” by Democrats and media of Bush-era hawks, claiming there is “little to no daylight between leading Democratic Party foreign policy gurus and the Bush-era neocons who had wallowed in disgrace following the debacle of Iraq”.

I can understand this – I’m of a similar age to Glenn, and I remember writing, in January and February 2003, to my UK Member of Parliament, Christine Russell (a loyal Blairite), pointing out that invading Iraq would result in humanitarian catastrophe and would increase rather than deter international terrorism threats. I still have the replies from Russell, and I still find it difficult to think of Blair or Jack Straw without a residue of anger.

So, it came as a big surprise when I read claims that Glenn Greenwald had actually supported the Iraq war. I checked this claim, of course. One of the first things I found was a somewhat defensive and repetitive denial from Glenn, who says the people making these claims are “fabricating” by making a “distortion” of the preface to his 2006 book, How Would a Patriot Act?. So, what’s the truth here?

In the preface to that book, Greenwald describes his reactions following the September 11, 2001 attacks in Manhattan:

“I was ready to stand behind President Bush and I wanted him to exact vengeance on the perpetrators and find ways to decrease the likelihood of future attacks. […] And I was fully supportive of both the president’s ultimatum to the Taliban and the subsequent invasion of Afghanistan when our demands were not met.” (Glenn Greenwald, ‘How Would a Patriot Act?‘)

During the later lead-up to the invasion of Iraq, Glenn was concerned that policy was being driven by “agendas and strategic objectives that had nothing to do with terrorism or the 9/11 attacks” and that “[t]he overt rationale for the invasion was exceedingly weak”. But, he goes on to write:

“Despite these doubts, concerns, and grounds for ambivalence, I had not abandoned my trust in the Bush administration. Between the president’s performance in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, the swift removal of the Taliban in Afghanistan, and the fact that I wanted the president to succeed, because my loyalty is to my country and he was the leader of my country, I still gave the administration the benefit of the doubt. I believed then that the president was entitled to have his national security judgment deferred to, and to the extent that I was able to develop a definitive view, I accepted his judgment that American security really would be enhanced by the invasion of this sovereign country.” (Glenn Greenwald, ‘How Would a Patriot Act?’)

The bottom line, then, is that even though Greenwald had concerns over Bush’s invasion policy, he accepted it anyway. He evidently also supported Bush’s “American security” rationale for this act of aggression, despite apparently being aware of its weakness.

Given his own words quoted back to him, how then does Greenwald deny that he supported the invasion of Iraq? Well, his argument is that since he didn’t actively promote, or publicly argue for, the policy of war (as he was neither a writer nor activist at the time) it follows that he didn’t support it. Those who claim he did are, he says, “fabricators” who make a “complete distortion” of the preface he wrote to his book (by accurately quoting it?).

Links for above: Greenwald tweet, Daily Kos piece

I don’t often use the term “horseshit”, but that’s what this sounds like to me. Greenwald denies supporting the war essentially by redefining “support” to mean something else. Public “support” is quite an important idea in democracies – we register our “support” for policies at elections and referendums; our “support” is measured by opinion polls or inferred in other ways. You don’t have to be a writer, activist or politician to support (or oppose) a war policy. Millions of US citizens misguidedly supported the invasion of Iraq by accepting Bush’s “national security” rationale and by giving his administration the “benefit of the doubt” – and that’s precisely what Greenwald did.

Most of those who point out that Glenn supported the war (Glenn says they’re liars) aren’t claiming he publicly promoted war. They’re quoting his 2006 book to show he supported the war in exactly the same way that countless other Americans supported the war – by not being neutral or opposing it; by accepting the case for it, on balance, and trusting those who waged it.

Greenwald repeatedly protests that, before 2004, he was “politically apathetic and indifferent”, “not politically engaged or active”, “was basically apolitical and passive”, “had no platform or role in politics”, “wasn’t a journalist or government official”, etc. You get the picture. But in all these respects he was like the vast majority who supported the war.

It’s obviously possible to be relatively “apolitical”, “passive”, etc, and still support a war. That’s how most people with pro-war views do support any given war policy – since most people aren’t hugely active politically as writers, campaigners, etc. Most, like Glenn, were engaged in other activities, such as full-time jobs, but were still able to form an opinion in support of the war – as Glenn did.

Incidentally, it’s not really true that a passive, acquiescing support of war is “apolitical”. On the contrary, any such acceptance of war requires underlying political beliefs, including what Lakoff calls the ‘Fairy Tale of the Just War’, built on ‘conservative’ framing of ‘self-defence’ or ‘rescue’ scenarios – see my Iraq War Framing for Dummies. The views that Greenwald describes himself as having on Iraq and Afghanistan, following 9/11, use the framing of a typically conservative political worldview: “American security really would be enhanced by the invasion”, “my trust in the Bush administration”, “my loyalty is to my country and he was the leader of my country”, “I wanted him to exact vengeance on the perpetrators”, etc.

The pre-2004 attributes that, according to Glenn, disqualified him from “supporting” the Iraq war (political apathy, no public platform, etc) oddly didn’t disqualify him from supporting the US invasion of Afghanistan. Perhaps the last word on this is a nice quote from Glenn, in which he admits supporting the war in Afghanistan, and then compares himself to Martin Luther King over his stance on Iraq:

“It is true that, like 90% of Americans, I did support the war in Afghanistan and, living in New York, believed the rhetoric about the threat of Islamic extremism: those were obvious mistakes. It’s also true that one can legitimately criticize me for not having actively opposed the Iraq War at a time when many people were doing so. Martin Luther King, in his 1967 speech explaining why his activism against the Vietnam War was indispensable to his civil rights work, acknowledged that he had been too slow to pay attention to or oppose the war and that he thus felt obligated to work with particular vigor against it once he realized the need…” (Glenn Greenwald, 26 January 2013)

Update – 19 Oct 2020: I notice this post is currently getting a lot of hits, seemingly related to social media activity arising from a piece by the independent researcher/journalist Marcy Wheeler (@emptywheel), which is also critical of Greenwald, and which has some interesting updates on Greenwald’s publication of Guccifer 2.0 material, as discussed above. Marcy Wheeler’s piece is available here.

Populist right – the mass appeal of “strict father” framing

George Lakoff’s book, Moral Politics, popularised the idea that ‘rightwing’ politics stem from a particular moral worldview, which Lakoff called “strict father framing”. Lakoff’s work unearthed, as it were, the cognitive root of prototypical “conservative” beliefs on a wide range of issues (from gun control to economics, from sex and abortion to war and the death penalty).

George Lakoff’s book, Moral Politics, popularised the idea that ‘rightwing’ politics stem from a particular moral worldview, which Lakoff called “strict father framing”. Lakoff’s work unearthed, as it were, the cognitive root of prototypical “conservative” beliefs on a wide range of issues (from gun control to economics, from sex and abortion to war and the death penalty).

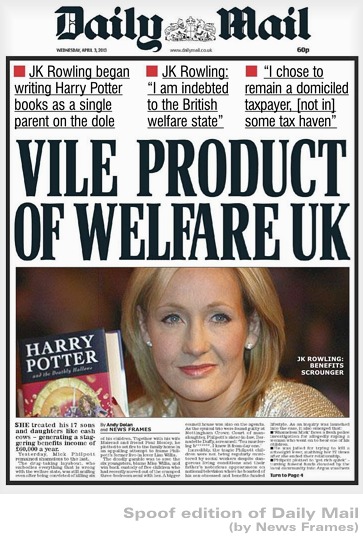

When I first read Moral Politics, it felt like a series of lightbulbs switching on inside my head. This was partly because I’d spent a lot of time modestly satirising ‘rightwing’ media views (eg for my Anxiety Culture zine), and I’d been particularly interested in tabloid newspaper obsessions with “spiralling crime”, “scroungers” and “red tape” obstructions to free-market “competitiveness” and “efficiency”. I didn’t know what united these particular ‘rightwing’ obsessions, but there seemed to be a common mindset behind them. Simply labelling them ‘rightwing’ or ‘conservative’ didn’t tell you what these views had as a common thread.

Lakoff’s cognitive theory seemed incredibly good at explaining and predicting the ways in which these views form – and how they all fit together – on all kinds of unrelated issues. The other side of the theory (nurturant framing), meanwhile, provided insights into my own ‘progressive’ views.

Why the rise of the populist right?

I’ve explained in a previous piece why I tend not to buy the “standard” explanations for the victories of Trump and Brexit. It’s not that mass hardship, inequality and animosity towards “establishment elites” (etc) aren’t factors. It’s just that they don’t account for the mass appeal specifically of populist right (including hard-right) views. Over 60 million Americans voted for a billionaire who has expressed beliefs ranging from the ominously authoritarian to the violently fascist. This didn’t happen by default.

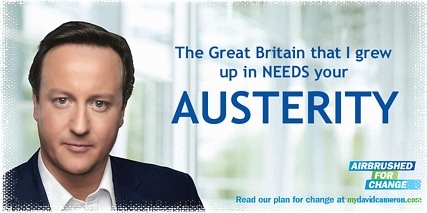

Before Brexit, in 2015, the Conservatives were voted back into UK government after years of painful economic austerity instituted by… the Conservatives. At the time, the Guardian’s Roy Greenslade documented how the rightwing press had “played a significant role in the Tory victory”. Although never expressed in the following terms, the role they played was to put a nationalist variant of “strict father” framing all over their front pages, regularly, on issues such as immigration, “stolen” jobs/benefits and interfering foreigners (eg EU bureaucrats). Meanwhile, Barack Obama said part of Trump’s success was down to “Fox News in every bar and restaurant in big chunks of the country”.

But beyond documenting mass discontent with the status quo and stating that the ‘rightwing’ media played a role, what else…?

No ‘leftwing’ model to explain ‘rightwing’ mass appeal?

For obvious reasons, most ‘left’/’liberal’ commentators don’t want to talk in terms of the “ignorance” or “stupidity” of the masses. They also don’t want to portray the majority as bigots (or “deplorables”), or patronisingly assert that the gullible public has been “brainwashed”. So what does that leave?

Most of the explanations I’ve read have simply concentrated on blaming “the liberal media”, the greed and aloofness of establishment elites, the failures of the Democratic campaign, the “liberal media”, the unpopularity of Hillary Clinton and the “liberal” media.

Did I mention “the liberal media”? I’m not even sure what that term commonly refers to anymore. Obviously something homogeneous and bad. Trump supporters, the ‘alt-right’, Corbynistas and the ‘radical’ left all seem to agree on the fungible awfulness of “the liberal media”.

But none of this explains the mass appeal of a specifically hard-right alternative (the 60+ million who voted for an Infowars-style bigot presumably counts as “mass appeal”). For that we need something else. Lakoff’s Moral Politics offers the best model that I’ve seen, to date, for understanding this phenomenon – and it has the advantage of being rooted in cognitive science. Even better, it gives us precise keys to understanding political language as well as worldviews. And it doesn’t require any postulating of mass stupidity, immorality or inherent bigotry in order to account for the mass appeal of hardline rightwing views of the type that Trump and his circle espouse.

I think the “strict father” frame thesis provides important clues to what is happening right now – crucial for the ‘progressive’ ‘left’ to understand. If you don’t have time to read Lakoff’s Moral Politics (or his shorter Don’t Think of an Elephant!), here’s my summary of how the “strict father” frame fits together. I’ve kept it non-technical and left out the jargony cognitive linguistics – it just gives an outline, a flavour of the frame itself…

The “strict father” frame

“Fear triggers the strict father model; it tends to make the model active in one’s brain.”

– George Lakoff, ‘Don’t think of an elephant’, p42

Lakoff makes the case that conservative moral values are based on a “strict father” upbringing model, and liberal (or ‘progressive’) values on a “nurturant parent” model. We all seem to have both models in our brains – even the most “liberal” person can understand a John Wayne film (Lakoff uses Arnold Schwarzenegger movies as examples of the ‘strictness’ moral system).

In the ‘strict father’ moral frame, the world is regarded as fundamentally dangerous and competitive. Good and bad are seen as absolutes, but children aren’t born good – they have to be made good through upbringing. This requires that they are obedient to a moral authority. Obedience is taught through punishment, which, according to this belief-system, helps children develop the self-discipline necessary to avoid doing wrong. Self-discipline is also needed for prosperity in a dangerous, competitive world. It follows, in this worldview, that people who prosper financially are self-disciplined and therefore morally good.

This framing complements, in obvious ways, the ideology of “free market” capitalism. For example, in the latter, the successful pursuit of self-interest in a competitive world is seen as a moral good since it benefits all via the “invisible hand” of the market. In both cases do-gooders are viewed as interfering with what is right – their “helpfulness” is seen as something which makes people dependent rather than self-disciplined. It’s also seen as an interference in the market optimisation of the benefits of self-interest.

Strictness Morality & competition

A ‘reward & punishment’ type morality follows from strictness framing. Punishment of disobedience is seen as a moral good – how else will people develop the self-discipline necessary to prosper in a dangerous, competitive environment? Becoming an adult, in this belief-system’s logic, means achieving sufficient self-discipline to free oneself from “dependence” on others (no easy task in a “tough world”). Success is seen as a just reward for the obedience which leads ultimately to self-discipline. Remaining “dependent” is seen as failure.

Competition is an important premise of Strictness Morality. By competing in a tough world, people demonstrate a self-discipline deserving of reward, ie success. Conversely, it’s seen as immoral to reward those who haven’t earned it through competition. By this logic, competition is seen as morally necessary: without it there’s no motivation to become the right kind of person – ie self-disciplined and obedient to authority. Constraints on competition (eg social “hand-outs”) are therefore seen as immoral.

‘Nurturant’ framing doesn’t give competition the same moral priority. ‘Progressive’ morality tends to view economic competition as creating more losers than winners, with the resulting inequality correlating with social ills such as crime, deprivation and all the things you hope won’t happen to you. The nurturant ideal of abundance for all (eg achieved through technological advance) works against the primacy of competition. Economic competition still has an important place, but as a limited (and fallible) means to achieving abundance, rather than as a moral imperative.

While nurturant morality is troubled by the fear of “not enough to go around for all”, strictness morality is haunted by the fear of personal failure, individual weakness. Even the “successful” seem haunted by this fear.

‘Moral strength’

Central to Strictness Morality is the metaphor of moral strength. “Evil” is framed as a force which must be fought. Weakness implies evil in this worldview, since weakness is unable to resist the force of evil.

People are not born strong, the logic goes; strength is built through learning self-discipline and self-denial – these are primary values in the strictness system, so any sign of weakness is a source of anxiety, and fear itself is perceived as a further weakness (one to be denied at all costs). Note that these views are all metaphorically conceived – instead of a force, evil could (outside the strictness frame) be viewed as an effect, eg of ignorance or greed – in which case strength wouldn’t make quite as much sense as a primary moral value.

It’s usually taken for granted that strength is “good” in concrete, physical ways, but we’re talking about metaphor here. Or, rather, we’re thinking metaphorically (mostly without being aware of the fact) – in a way which affects our hierarchy of values. With “strictness” framing, we’ll give higher priority to strength (discipline, control) than to tolerance (fairness, compassion, etc). This may influence everything from our relationships to our politics and how we evaluate our own mental-emotional states.

‘Authoritarian’ moral framing

We’re constrained by ‘social attitudes’ which put moral values in a different order than our own. Moral conflicts aren’t just about “good” vs “bad” – they’re about conflicting hierarchies of values.

For example, you mightn’t regard hard work or self-discipline as the main indicators of a person’s worth – but someone with economic power over you (eg your employer) might. To give an example of how different moral hierarchies lead to conflicting political views, consider welfare. From the ‘progressive’ viewpoint, welfare is generally regarded as morally good – the notion of a social ‘safety net’ appeals to a moral hierarchy in which caring and compassion are primary values. Strict conservatism, on the other hand, tends to view welfare not just as an economic drain, but as immoral. You get a sense of this when it’s framed as “rewarding people for sitting around doing nothing”. Here are the steps in ‘strict’ moral logic which lead to the view that welfare is immoral:

1. “Laziness is bad”. Under ‘strictness’ morality, self-indulgence (eg idleness) is seen as moral weakness, ie emergent evil. It represents a failure to develop the ‘moral strengths’ of self-control and self-discipline (which are primary values in this worldview).

2. “Time-wasting is very bad”. Laziness also implies wasted time according to this viewpoint. So it’s ‘bad’ in the further sense that “time is money”. Inactivity and idleness are seen as inherently costly, a financial loss. People tend to forget that this is metaphorical – there is no literal “loss” – and the frame excludes notions of benefits (or “gains”) resulting from inaction/indolence.

3. “Welfare is very, very bad”. Regarded (by some) as removing the “incentive” to work, welfare is thus seen as promoting moral weakness (ie laziness, time-wasting, “dependency”, etc). That’s bad enough in itself (from the perspective of Strictness Morality) – but, in addition, welfare is usually funded by taxing those who work. In other words, the “moral strength” of holding a job isn’t being rewarded in full – it’s being taxed to reward the “undeserving weak”.

3. “Welfare is very, very bad”. Regarded (by some) as removing the “incentive” to work, welfare is thus seen as promoting moral weakness (ie laziness, time-wasting, “dependency”, etc). That’s bad enough in itself (from the perspective of Strictness Morality) – but, in addition, welfare is usually funded by taxing those who work. In other words, the “moral strength” of holding a job isn’t being rewarded in full – it’s being taxed to reward the “undeserving weak”.

Thus welfare is seen as doubly immoral in this system of moral metaphors. (Donald Trump uses typical ‘strict father’ framing on the issue of welfare. He believes that benefits discourage people from working: “People don’t have an incentive,” he said to Sean Hannity during his campaign. “They make more money by sitting there doing nothing than they make if they have a job.”).

“Might is right”

In ‘strict father’ morality, one must fight evil (and never “understand” or tolerate it). This requires strength and toughness and, perhaps, extreme measures. Merciless enforcement of might is often regarded as ‘morally justified’ in this system. Moral “relativism” is viewed as immoral, since it “appeases” the forces of evil by affording them their own “truth”.

“We don’t negotiate with terrorists… I think you have to destroy them. It’s the only way to deal with them.” (Dick Cheney, former US Vice President)

There’s another sense in which “might” (or power) is seen as not only justified (eg in fighting evil) but also as implicitly good: Strictness Morality regards a “natural” hierarchy of power as moral, and in this conservative moral system, the following hierarchy is (according to Lakoff’s research) regarded as truly “natural”: “God above humans”; “humans above animals”; “men above women”; “adults above children”, etc.

So, the notion of ‘Moral Authority’ arises from a power hierarchy which is believed to be “natural” (as in: “the natural order of things”). Lakoff comments:

“The consequences of the metaphor of Moral Order are enormous, even outside religion. It legitimates a certain class of existing power relations as being natural and therefore moral, and thus makes social movements like feminism appear unnatural and therefore counter to the moral order.” (George Lakoff, Moral Politics, p82)

In this metaphorical reality-tunnel, the rich have “moral authority” over the poor. The reasoning is as follows: Success in a competitive world comes from the “moral strengths” of self-discipline and self-reliance – in working hard at developing your abilities, etc. Lack of success, in this worldview, implies not enough self-discipline, ie moral weakness. Thus, the “successful” (ie the rich) are seen as higher in the moral order – as disciplined and hard-working enough to “succeed”.

‘Erosion of values’ & ‘moral purity’

Media hysteria sometimes calms down a little. But it only takes one horrible crime or indication of ‘Un-American’ behaviour (etc) to set it off again. Then we have: “erosion of values”, “tears in the moral fabric”, a “chipping away” at moral “foundations”, “moral decay”, etc. It shouldn’t be surprising that these metaphors for change-as-destruction tend to accompany ‘conservative’ moral viewpoints rather than ‘progressive’ ones.

Associated with moral ‘decay’ is the metaphor of impurity, ie rot, corruption or filth. This extends further, to the metaphor of morality as health. Thus, immoral ideas are described as “sick“, immoral people are seen to have “diseased minds”, etc. These metaphorical frames have the following consequences in terms of how we think:

1. Even minor immorality is seen as a major threat (since introduction of just a tiny amount of “corrupt” substance can taint the whole supply – think of water reservoir or blood supply. This is applied to the abstract moral realm via conceptual metaphor.)

2. Immorality is regarded as “contagious”. Thus, immoral ideas must be avoided or censored, and immoral people must be isolated or removed, forcibly if necessary. Otherwise they’ll “infect” the morally healthy/strong. Does this way of thinking sound familiar? (This framing has taken scaremongering forms in the Brexit and Trump campaigns).

In Philosophy in the Flesh, Johnson & Lakoff point out that with “health” as metaphor for moral well-being, immorality is framed as sickness and disease, with important consequences for public debate:

“One crucial consequence of this metaphor is that immorality, as moral disease, is a plague that, if left unchecked, can spread throughout society, infecting everyone. This requires strong measures of moral hygiene, such as quarantine and strict observance of measures to ensure moral purity. Since diseases can spread through contact, it follows that immoral people must be kept away from moral people, lest they become immoral, too. This logic often underlies guilt-by-association arguments, and it often plays a role in the logic behind urban flight, segregated neighborhoods, and strong sentencing guidelines even for nonviolent offenders.”

Enemies everywhere, everything a threat

There’s a lot to fear from the perspective of ‘strictness morality’: the world’s a dangerous place, there’s immorality and “evil” lurking everywhere – an ever-present threat from the “foreign” and “alien”. And any weakness that you manifest will be punished. Even the good, decent people are competing ruthlessly with you, judging you for any failure.

In a way, this moral framing logically requires that the world is seen as essentially dangerous. Remove this premise and strictness morality ‘collapses’, since the precedence given (in this scheme) to moral strength, self-discipline and authority (over compassion, fairness, happiness, etc) would no longer make sense.

Rightwing media (tabloid newspapers, Fox News, etc) appear to have the function of reinforcing the fearful premise with daily scaremongering – presumably because it’s more profitable than less dramatic “news”. But this repeated stimulation of our fears affects us at a synaptic level. The fear/alarm framing receives continual reinforcement, triggering the ‘strict father’ worldview, making the model more active, more dominant in our brains.

Update (23/1/2017) – see George Lakoff’s comments on Trump’s inaugural speech. Lakoff says “Trump is a textbook example of Strict Father Morality”, but he also gives some clues on Trump’s weaknesses and how to defeat him (for example, Trump is already a “betrayer of trust” – seen as a big sin in strict father morality).

Conservative framing of welfare

Jan 22, 2015 – With each example seen in the media (and not just in the rightwing tabloids) it’s tempting to see conservative framing of welfare as simply crass, vicious and stupid. But that doesn’t help us understand why demonisation of benefits recipients seems popular with large sections of the public (witness the popularity of the Benefits Street style TV shows and the rise of UKIP, etc). A cognitive frames approach helps us to get a better insight into the phenomenon…

Jan 22, 2015 – With each example seen in the media (and not just in the rightwing tabloids) it’s tempting to see conservative framing of welfare as simply crass, vicious and stupid. But that doesn’t help us understand why demonisation of benefits recipients seems popular with large sections of the public (witness the popularity of the Benefits Street style TV shows and the rise of UKIP, etc). A cognitive frames approach helps us to get a better insight into the phenomenon…

The differences between “conservative” and “progressive” (or “liberal”) views on welfare have little to with fact and logic. It’s more about opposing metaphorical framing on morality. This framing underlies much of the “social” policy of the right.

1. Conservative view of social welfare:

Welfare seen as essentially “immoral” because:

- It’s viewed as encouraging “dependence” on the government, and so is against the morality of self-reliance & self-discipline.

- It’s not given to everyone, so it introduces competitive unfairness, an interference with the “free market”, and hence with the “fair” pursuit of self-interest (part of the morality of reward and punishment).

- Since it’s paid for by tax, it “takes” money from someone who has earned it, and gives it to someone who hasn’t (against the morality of rewarding self-reliant, self-disciplined people).

Note the particular moral emphasis here: self-reliance, self-discipline, reward and punishment. George Lakoff has documented at length how these values are central to conservative framing (eg in his books, Whose Freedom? and Moral Politics). Moral differences don’t just concern different ideas about “good” vs “bad” – they’re about conflicting hierarchies of values. Liberal/progressive views hold “empathy”, “care”, etc, as primary in moral terms, with self-discipline and self-reliance secondary in moral importance. The inverse is true for conservative (or what Lakoff calls “strict father”) morality.

This doesn’t imply crude either/or reductionism or simplistic stereotyping of people. Different value-hierarchies may apply for a given individual depending on the domain she/he is conceptualisng. For example, some people describe themselves as socially liberal but economically conservative.

Rightwing strategy (via think-tanks & conservative media) has been to repeatedly use the metaphorical language of “strictness” on domains which may have been traditionally framed more in terms of looking after others – ie caring. The economic value-hierarchies of the businessperson thus gradually replace a moral scheme in which notions such as “social security” and “safety net” represented primary values. This entails a moral shift, a change in what’s regarded as normal, acceptable “common sense” (and also, according to some cognitive scientists, an accompanying physical change in our brains).

To quote Lakoff’s Moral Politics:

The basis of the classification of successful businessmen as model citizens is very deep, as we have seen. It is the principle of the Morality of Reward and Punishment, which is at the heart of Strict Father morality. To place restrictions on that principle is to strike at the heart of conservative ethics and the conservative way of life. Placing restrictions on moral people who are engaged in moral activities is immoral. (Chapter 12)

Welfare, government regulation, etc, are thus seen as immoral interferences in a moral system of rewarding “success” in a competitive world. This framing encompasses, in obvious ways, the system of “free market” capitalism. For example, in the latter, the successful pursuit of self-interest in a competitive world is seen as a moral good since it benefits all via the “invisible hand” of the market. In both cases do-gooders are viewed as interfering with what is right – their “helpfulness” is seen as something which makes people dependent rather than self-disciplined. It’s also seen as an interference in the market optimisation of the benefits of self-interest.

Under this moral frame, cuts in welfare (etc) are not just seen as a temporary measure of “austerity” (eg until the economy recovers) – they’re seen as a moral imperative for all time, since the alternative is viewed as fundamentally immoral.

2. Conservative view of corporate welfare:

But what about corporate welfare? Given the above reasoning, shouldn’t conservatives view that, also, as immoral according to this framing?

Corporate welfare not (immediately) seen as immoral because:

- Those receiving it are pre-conceptualised as self-reliant and self-disciplined in the entrenched iconography of the heroic, hard-working, successful “wealth creator”. Under the conservative moral accounting metaphor, they are seen as deserving.

- The comparison between corporate welfare and social welfare thus doesn’t work on most conservatives (at least not without years of reframing), because the heroes and demons in the conservative worldview are based on “deep” cultural metaphors reflecting the primary morality of self-discipline and self-reliance. This takes the form of: “Why shouldn’t the best people be rewarded – their success demonstrates their self-discipline”, etc.

For a more in-depth look at moral-political framing systems, please see our Essentials of Framing.

Moral outrage on tap

W A R N I N G :

W A R N I N G :

Repeated dosage of Moral Outrage

may turn you conservative.

July 31, 2014 – Individuals have been doing “sickening”, “disgusting” things since… well, at least since the beginning of recorded history. And if we accept that it’s important to ruminate on the terrible acts of strangers, then there’s an endless supply to choose from. We can be 24-Hour Outraged People. It’s our moral obligation.

You may laugh at that reductio, but have you looked at “quality” newspaper comment pages or popular web forums recently? Moral outrage has become such a ready, familiar mode of cognition – and expression – that it functions like a sort of currency, particularly in online social “transactions”.

Unfortunately, moral outrage – like fear – tends to activate authoritarian conceptual frames while it inhibits empathy. Empathy precludes the perception of a human being as a “monster”, “animal”, “sub-human scum”, etc. That much seems obvious. But perhaps it’s less obvious that headlines which repeatedly refer to human beings only by the crimes of which they’re convicted (or merely accused) – eg “The Predator”, “The Welfare Cheat”, “The Racist” – will tend to inhibit, in a broader way, the experience of “empathy” on which progressive morality (and, generally, “liberal” politics) is based. Empathy is towards other people (including, but not limited to, victims). Moral outrage is exclusively concentrated on what seems “lower” than human.

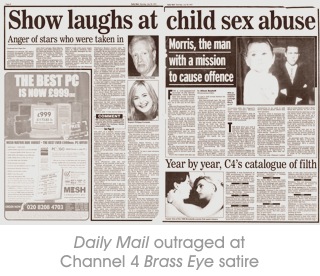

There was a time – not long ago – when newspapers such as the News of the World got a lot of mileage from “paedo” hysteria. Chris Morris’s Channel 4 comedy, Brass Eye (full video here), satirised this “coverage” hilariously, capturing all its absurdity and hypocrisy. And then, of course, the Daily Mail (and others – including government ministers) turned their outrage on Morris and Channel 4. How dare they joke about such a serious subject?

There was a time – not long ago – when newspapers such as the News of the World got a lot of mileage from “paedo” hysteria. Chris Morris’s Channel 4 comedy, Brass Eye (full video here), satirised this “coverage” hilariously, capturing all its absurdity and hypocrisy. And then, of course, the Daily Mail (and others – including government ministers) turned their outrage on Morris and Channel 4. How dare they joke about such a serious subject?

Channel 4, and other commentators in the more “liberal” areas of the press, rightly shrugged, sighed, and effectively said: “You idiots, can’t you see that it’s satire, and that it’s satirising media coverage, and in particular the type of reaction we’re getting from you right now”.

July 19, 2001

Chris Morris, the satirist who tricked politicians into railing against a fake drug “cake”, has caused controversy again by duping celebrities into endorsing two fabricated anti-paedophilia campaigns for his latest TV series.

A furious Phil Collins last night said he was taking legal advice after having been filmed with a T-shirt bearing the words “Nonce Sense” while giving “advice” to children. […]

The programme, clearly designed to satirise the hysteria surrounding the issue last year, was due to be shown earlier in the month.

I wonder if the Guardian and Channel 4 would take the same progressive view towards such satire in today’s climate (post- Jimmy Savile type scandals, etc). Given some of the Guardian’s recent attacks on the satiric humour of The Onion, the creator of Family Guy, Reginald D. Hunter’s ironic use of the “N” word, etc, I’m not too confident they would.

Certain types of moral outrage – like fearmongering – should probably be viewed as a media virus, or a special type of contrived “news” frame. Repeated often, and widely (a bit of moral outrage with breakfast every morning), they strengthen the neural connections on which this mode of cognition are based. Of course, in the “liberal” press it’s (mostly) directed at different things than in the rightwing tabloids. But the logic of the currently fashionable “zero tolerance” type framing applies to both, together with a tendency to demonise individuals (as opposed to simply condemning the crime/”crime”).

Why do these tendencies reinforce conservative moral systems? Because they’re based on conservative (authoritarian, so-called “strict father”) premises such as tolerance-as-weakness, character weakness as direct cause of immorality, etc. These moral premises may be unspoken (and unconscious), but they directly oppose the progressive morality of tolerance-as-virtue, compassion/empathy as ‘integral’ with systemic causation, etc.

I’ve previously written about the Luis Suarez saga(s), and how media outrage appeared (to put it mildly) disproportionate to the actions of one individual. The Guardian was probably the worst in terms of sheer volume of moral outrage (exceeding the tabloids in this regard). The emotion released apparently so warped the perceptions of some journalists, that they routinely got the facts wrong (one senior sports reporter for The Independent admitted to me, by email, that he had indeed made some erroneous, and fairly serious, accusations – these were never corrected in the newspaper).

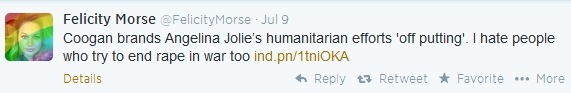

Another recent (slightly less emotive) case concerned a magazine “report” that Steve Coogan had been dismissively critical of Angelina Jolie’s humanitarian campaigning. This “story” was soon republished by others (eg The Independent) and, by the churnalism process, became this claim: “STEVE Coogan claims Angelina Jolie’s efforts to help refugees and rid wars of rape is ‘off-putting’.” An army of tweeters then expressed their moral outrage at Coogan. Felicity Morse, the Independent’s social media editor (whose tweets I mostly enjoy), tweeted the following to her 15,000 followers:

The implication was that Coogan “hates” those who “try to end rape in war”. A serious, reputation-damaging suggestion. As it turned out, the report was completely wrong – Coogan’s remarks weren’t directed at Jolie at all. To me, the problem was not so much that the report was later confirmed to be wrong, but that you could see beforehand that the claims didn’t logically follow from the quotes attributed to Coogan. (I had gently warned Felicity about this immediately after her tweet – to no avail. Moral outrage has its own logic, its own course to run).

The Independent later amended its article, but only enough to save face. The headline (which now reads: Steve Coogan appears to brand Angelina Jolie’s humanitarian efforts ‘off-putting’…) is still misleading, since the whole premise on which the story was based has evaporated.

There are many more cases. In fact, they now seem a daily occurrence. What used to be a regular staple of the worse tabloid rags now appears to be a large part of what fills space in supposedly progressive newspapers such as the Guardian and Independent (particularly on their websites, where space is unlimited). In the latter cases, the issues referenced (eg anti-racism, anti-sexism) may be progressive, unlike in the tabloids. But the underlying moral framing of outrage looks the same – the Trojan horse of ‘zero tolerance’ and the conservative logic of essences and moral ‘character’.

Note: I hope I don’t alienate any of my readers with the above. I often feel morally outraged at events, both distant and close to me – it’s not something I demean. My purpose has been to focus on one particular ‘framing’ aspect of moral outrage – something that, to my knowledge, nobody else has focused on.

Lazy Person’s Guide to Framing

I’m pleased to say that a book, Lazy Person’s Guide to Framing, which I’ve been working on for a while, is now available in Kindle edition. You can get it from Amazon UK or Amazon US. Read the 5-star reviews at Amazon UK.

I’m pleased to say that a book, Lazy Person’s Guide to Framing, which I’ve been working on for a while, is now available in Kindle edition. You can get it from Amazon UK or Amazon US. Read the 5-star reviews at Amazon UK.

It hovered at around #4 Amazon bestseller rating in Amazon’s ‘Propaganda & Spin’ category for the first few weeks after release (reaching #2 at one point).

This is from the book’s blurb:

Lazy Person’s Guide to Framing:

Decoding the news media

Futura Press (30 Jun 2014)

ISBN: 978-0-9562179-2-9

From Futura Pocketbooks, a “Lazy Person’s Guide” to media framing, which explains how headlines and news stories can be decoded using the latest know-how from the cognitive sciences. Find out how media narratives and political spin are unravelled and deciphered by “frame semantics” – an essential part of what has been labelled, “The Cognitive Revolution”. This is a fun and highly readable guide, written especially for the layperson, which, in the tradition of George Lakoff (author of Don’t Think of an Elephant), popularises the new linguistic field in a way that makes it accessible and deeply relevant for anyone concerned by the power wielded by those who “frame the message” in media and politics.

As the book shows, framing is far more than just a respectable form of spin or wordplay. Frames are mental structures which shape our worldviews. They structure the way we reason, and define what we take to be “common sense” – yet our use of frames is largely unconscious and reflexive. This has a huge bearing on politics and media. The book investigates many examples of political and news frames, from so-called “benefit tourists” and “flatlined economy”, to the moral framing of war, crime and “responsibility”, etc.

Lakoff in Guardian

Feb 5, 2014 – Just a brief post to: a) point to a smart Guardian piece on George Lakoff’s ideas, and b) express my frustration (ranty prose ahead) at the level of ignorance/idiocy on the topic of framing that I see in feedback on newspaper comments sections, Twitter etc.

Feb 5, 2014 – Just a brief post to: a) point to a smart Guardian piece on George Lakoff’s ideas, and b) express my frustration (ranty prose ahead) at the level of ignorance/idiocy on the topic of framing that I see in feedback on newspaper comments sections, Twitter etc.

I’ve found Twitter useful for searches. For example, a search on “lakoff” brought up tweets linking to Zoe Williams’s new Guardian article (well worth taking the time to read). Unfortunately, the same search brings up an assortment of not-so-knowledgeable reactions to the article, and to Lakoff’s ideas in general.

It’s the same with the “post a response” sections underneath online newspaper articles. Tom Hodgkinson (editor of The Idler) recently put it this way:

“At the foot of the article sat a collection of ‘comments’ by the usual collection of morons. Anyone who believes in the democratization of journalism should check out the dimwits who gather ‘below the line’. The Telegraph ones seemed even more big-headed and stupid than the Guardian ones, if that’s possible.” *

Zoe Williams’s article states that Lakoff prescribes “the abandonment of argument by evidence in favour of argument by moral cause”, which is understandable within the context of Lakoff’s cognitive-linguistics work on how we think (eg in political frames). But to someone who isn’t familiar with Lakoff’s academic books, and the emphasis he places on empirical research, the notion of abandoning “argument by evidence” (and the notion that “facts” “weaken” political beliefs) probably confirms their ignorance-derived suspicions that framing subverts “reason” in a bad way. Indeed, the first response to Williams’s article was this:

Interestingly, the Guardian article attracted less than 50 comments – low compared to the number Zoe William’s articles usually get. That’s probably because it was hidden away in the ‘Philosophy’ section of the Guardian site, rather than in the more-publicised ‘Comment is Free’ area – a strange decision by whoever was responsible (it’s happened before with Lakoff-themed pieces) given that the article seems more topical and comment-worthy than much of the frivolous space-filler published in CiF. Williams’s article was also posted (pirated? stolen?) at the “independent” media sites, AlterNet and The Raw Story, where, in both cases, it attracted several hundred comments (many of them as stupid and/or ignorant as the ones you get at online corporate media). I hope those sites pay Zoe something for her work, or at least asked her permission to publish.

Moving back to Twitter. One of my “lakoff” searches brought up the following:

It turns out that both of these Tweeters write for the Guardian and New Left Project (and one of them follows me on Twitter). So I can’t quickly dismiss such remarks as ignorant Twitterish. But I find it a tad frustrating: you don’t have to read the complete Lakoff oeuvre to see that he doesn’t “ignore” those things mentioned in the tweet. Probably just one of his books is sufficient to show that. To dig deeper, there’s a rich treatment of the “libertarian-authoritarian axis” in his work on moral politics. The academic work on conceptual metaphor, prototype and narrative will likely give you more new insights into the “difference between sales pitch and product” than you’ll find in 99.9% of political commentary (including the “radical left” variety).

As for “ignoring” “big money”, the irony is that Lakoff’s political books (Whose Freedom, Don’t Think of an Elephant, etc) seem motivated by his concern precisely at the way “big money” – via the giant, massively-funded rightwing messaging machine, acting through the mass media – has managed to shape our thinking for decades, at the level of what we think of as “common sense”. This is a constantly recurring theme in Lakoff’s books, together with his treatment of “free market” ideology and what he calls the ‘Economic Liberty Myth’.

Note: If you were perplexed by the notion of making evidence and facts less prominent in political argument, I’d recommend the following passages from Lakoff’s Thinking Points, to give a flavour of what he is saying:

We think and reason using frames and metaphors. The consequence is that arguing simply in terms of facts—how many people have no health insurance, how many degrees Earth has warmed in the last decade, how long it’s been since the last raise in the minimum wage—will likely fall on deaf ears. That’s not to say the facts aren’t important. They are extremely important. But they make sense only given a context. […]

We were not brought up to think in terms of frames and metaphors and moral worldviews. We were brought up to believe that there is only one common sense and that it is the same for everyone. Not true. Our common sense is determined by the frames we unconsciously acquire […] The discovery of frames requires a reevaluation of rationalism, a 350-year-old theory of mind that arose during the Enlightenment. We say this with great admiration for the rationalist tradition. It is rationalism, after all, that provided the foundation for our democratic system. […] But rationalism also comes with several false theories of mind.

We know that we think using mechanisms like frames and metaphors. Yet rationalism claims that all thought is literal, that it can directly fit the world; this rules out any effects of framing, metaphors, and worldviews. We know that people with different worldviews think differently and may reach completely different conclusions given the same facts. But rationalism claims that we all have the same universal reason. Some aspects of reason are universal, but many others are not—they differ from person to person based on their worldview and deep frames.

We know that people reason using the logic of frames and metaphors, which falls outside of classical logic. But rationalism assumes that thought is logical and fits classical logic.

If you believed in rationalism, you would believe that the facts will set you free, that you just need to give people hard information, independent of any framing, and they will reason their way to the right conclusion. We know this is false, that if the facts don’t fit the frames people have, they will keep the frames (which are, after all, physically in their brains) and ignore, forget, or explain away the facts.

If you were a rationalist policy maker, you would believe that frames, metaphors, and moral worldviews played no role in characterizing problems or solutions to problems. You would believe that all problems and solutions were objective and in no way worldview dependent. You would believe that solutions were rational, and that the tools to be used in arriving at them included classical logic, probability theory, game theory, cost-benefit analysis, and other aspects of the theory of rational action.

Rationalism pervades the progressive world. It is one of the reasons progressives have lately been losing to conservatives. Rationalist-based political campaigns miss the symbolic, metaphorical, moral, emotional, and frame-based aspects of political campaigns.

* From Hodgkinson’s Register, mailed on 29/10/13.

Hating the “right” group

Group generalisations can lead to horrors – even when motivated by benign causes

[Updated 27/5/14] – Following the 20th Century nightmares of concentration camps, mass slaughter of certain groups, etc, I think it was widely understood – for a while at least – that Nazi ideology was abominable not because it directed hatred towards the wrong groups, but because hating any group seems nonsensical and eventually leads to violence. When people are perceived as mere units of group identity, dehumanising horrors can result – as history has repeatedly shown.

This insight seems lost – to the extent that it now seems fashionable, or “radical”, to hate groups that are believed, from a position of moral rectitude, to be deserving of hatred. For example, it even seems a badge of honour in some “radical left” circles to uncompromisingly despise the group classed as “corporate journalists” – since, by definition, it’s a subset of the larger “corporate” class, which is to be righteously reviled because of the mass suffering and destruction to the planet caused by corporations and the corporate system.

(There’s a “radical right” version of this in which the group known as the “liberal elite media” is hated as being a subset of the larger elite “liberal” class. There are also gender-based versions which follow a similar logic).

So, fungible group hatred has become respectable – as long as it’s the right group. And the “debate” between Left and Right now consists largely of: “Which are the correct groups to vilify?”

Despising ideas, beliefs, policies, actions, etc, attributed to a group, isn’t the problem. Rather, the problem seems to appear when unacknowledged mental processes result in false inferences about individual people, based on classing them as units of a group-abstraction.

Try describing the “reality” of any individual human being in terms of what defines any given group (social, political, religious, ethnic, racial, gender, whatever), and you will likely invoke the – usually unconscious – logic of “essences” (which Aristotle originally spelt out, but which has always been pervasive in folklore). It’s also the logic of medieval demonology, and, to quote Lakoff, “the logic of essences is all over conservative thought” (The Political Mind, p79).

Absolute categorisation of individuals based on this Aristotelian (or folk) logic of “indwelling (group) essences” shouldn’t be confused with the scientific approach of calculating statistical probabilities about nominal members of a group based on empirical data. But it would take more than a brief blog post to do justice to this whole area.

(For background, you could do worse than watching The Crucible – starring Winona Ryder & Daniel Day-Lewis. Or read: The Semantics of “Good” & “Evil” for more on Aristotelian logic & demonology).

Žižek on Lakoff