Archive for the ‘Fearmongering’ Category

Populist right – the mass appeal of “strict father” framing

George Lakoff’s book, Moral Politics, popularised the idea that ‘rightwing’ politics stem from a particular moral worldview, which Lakoff called “strict father framing”. Lakoff’s work unearthed, as it were, the cognitive root of prototypical “conservative” beliefs on a wide range of issues (from gun control to economics, from sex and abortion to war and the death penalty).

George Lakoff’s book, Moral Politics, popularised the idea that ‘rightwing’ politics stem from a particular moral worldview, which Lakoff called “strict father framing”. Lakoff’s work unearthed, as it were, the cognitive root of prototypical “conservative” beliefs on a wide range of issues (from gun control to economics, from sex and abortion to war and the death penalty).

When I first read Moral Politics, it felt like a series of lightbulbs switching on inside my head. This was partly because I’d spent a lot of time modestly satirising ‘rightwing’ media views (eg for my Anxiety Culture zine), and I’d been particularly interested in tabloid newspaper obsessions with “spiralling crime”, “scroungers” and “red tape” obstructions to free-market “competitiveness” and “efficiency”. I didn’t know what united these particular ‘rightwing’ obsessions, but there seemed to be a common mindset behind them. Simply labelling them ‘rightwing’ or ‘conservative’ didn’t tell you what these views had as a common thread.

Lakoff’s cognitive theory seemed incredibly good at explaining and predicting the ways in which these views form – and how they all fit together – on all kinds of unrelated issues. The other side of the theory (nurturant framing), meanwhile, provided insights into my own ‘progressive’ views.

Why the rise of the populist right?

I’ve explained in a previous piece why I tend not to buy the “standard” explanations for the victories of Trump and Brexit. It’s not that mass hardship, inequality and animosity towards “establishment elites” (etc) aren’t factors. It’s just that they don’t account for the mass appeal specifically of populist right (including hard-right) views. Over 60 million Americans voted for a billionaire who has expressed beliefs ranging from the ominously authoritarian to the violently fascist. This didn’t happen by default.

Before Brexit, in 2015, the Conservatives were voted back into UK government after years of painful economic austerity instituted by… the Conservatives. At the time, the Guardian’s Roy Greenslade documented how the rightwing press had “played a significant role in the Tory victory”. Although never expressed in the following terms, the role they played was to put a nationalist variant of “strict father” framing all over their front pages, regularly, on issues such as immigration, “stolen” jobs/benefits and interfering foreigners (eg EU bureaucrats). Meanwhile, Barack Obama said part of Trump’s success was down to “Fox News in every bar and restaurant in big chunks of the country”.

But beyond documenting mass discontent with the status quo and stating that the ‘rightwing’ media played a role, what else…?

No ‘leftwing’ model to explain ‘rightwing’ mass appeal?

For obvious reasons, most ‘left’/’liberal’ commentators don’t want to talk in terms of the “ignorance” or “stupidity” of the masses. They also don’t want to portray the majority as bigots (or “deplorables”), or patronisingly assert that the gullible public has been “brainwashed”. So what does that leave?

Most of the explanations I’ve read have simply concentrated on blaming “the liberal media”, the greed and aloofness of establishment elites, the failures of the Democratic campaign, the “liberal media”, the unpopularity of Hillary Clinton and the “liberal” media.

Did I mention “the liberal media”? I’m not even sure what that term commonly refers to anymore. Obviously something homogeneous and bad. Trump supporters, the ‘alt-right’, Corbynistas and the ‘radical’ left all seem to agree on the fungible awfulness of “the liberal media”.

But none of this explains the mass appeal of a specifically hard-right alternative (the 60+ million who voted for an Infowars-style bigot presumably counts as “mass appeal”). For that we need something else. Lakoff’s Moral Politics offers the best model that I’ve seen, to date, for understanding this phenomenon – and it has the advantage of being rooted in cognitive science. Even better, it gives us precise keys to understanding political language as well as worldviews. And it doesn’t require any postulating of mass stupidity, immorality or inherent bigotry in order to account for the mass appeal of hardline rightwing views of the type that Trump and his circle espouse.

I think the “strict father” frame thesis provides important clues to what is happening right now – crucial for the ‘progressive’ ‘left’ to understand. If you don’t have time to read Lakoff’s Moral Politics (or his shorter Don’t Think of an Elephant!), here’s my summary of how the “strict father” frame fits together. I’ve kept it non-technical and left out the jargony cognitive linguistics – it just gives an outline, a flavour of the frame itself…

The “strict father” frame

“Fear triggers the strict father model; it tends to make the model active in one’s brain.”

– George Lakoff, ‘Don’t think of an elephant’, p42

Lakoff makes the case that conservative moral values are based on a “strict father” upbringing model, and liberal (or ‘progressive’) values on a “nurturant parent” model. We all seem to have both models in our brains – even the most “liberal” person can understand a John Wayne film (Lakoff uses Arnold Schwarzenegger movies as examples of the ‘strictness’ moral system).

In the ‘strict father’ moral frame, the world is regarded as fundamentally dangerous and competitive. Good and bad are seen as absolutes, but children aren’t born good – they have to be made good through upbringing. This requires that they are obedient to a moral authority. Obedience is taught through punishment, which, according to this belief-system, helps children develop the self-discipline necessary to avoid doing wrong. Self-discipline is also needed for prosperity in a dangerous, competitive world. It follows, in this worldview, that people who prosper financially are self-disciplined and therefore morally good.

This framing complements, in obvious ways, the ideology of “free market” capitalism. For example, in the latter, the successful pursuit of self-interest in a competitive world is seen as a moral good since it benefits all via the “invisible hand” of the market. In both cases do-gooders are viewed as interfering with what is right – their “helpfulness” is seen as something which makes people dependent rather than self-disciplined. It’s also seen as an interference in the market optimisation of the benefits of self-interest.

Strictness Morality & competition

A ‘reward & punishment’ type morality follows from strictness framing. Punishment of disobedience is seen as a moral good – how else will people develop the self-discipline necessary to prosper in a dangerous, competitive environment? Becoming an adult, in this belief-system’s logic, means achieving sufficient self-discipline to free oneself from “dependence” on others (no easy task in a “tough world”). Success is seen as a just reward for the obedience which leads ultimately to self-discipline. Remaining “dependent” is seen as failure.

Competition is an important premise of Strictness Morality. By competing in a tough world, people demonstrate a self-discipline deserving of reward, ie success. Conversely, it’s seen as immoral to reward those who haven’t earned it through competition. By this logic, competition is seen as morally necessary: without it there’s no motivation to become the right kind of person – ie self-disciplined and obedient to authority. Constraints on competition (eg social “hand-outs”) are therefore seen as immoral.

‘Nurturant’ framing doesn’t give competition the same moral priority. ‘Progressive’ morality tends to view economic competition as creating more losers than winners, with the resulting inequality correlating with social ills such as crime, deprivation and all the things you hope won’t happen to you. The nurturant ideal of abundance for all (eg achieved through technological advance) works against the primacy of competition. Economic competition still has an important place, but as a limited (and fallible) means to achieving abundance, rather than as a moral imperative.

While nurturant morality is troubled by the fear of “not enough to go around for all”, strictness morality is haunted by the fear of personal failure, individual weakness. Even the “successful” seem haunted by this fear.

‘Moral strength’

Central to Strictness Morality is the metaphor of moral strength. “Evil” is framed as a force which must be fought. Weakness implies evil in this worldview, since weakness is unable to resist the force of evil.

People are not born strong, the logic goes; strength is built through learning self-discipline and self-denial – these are primary values in the strictness system, so any sign of weakness is a source of anxiety, and fear itself is perceived as a further weakness (one to be denied at all costs). Note that these views are all metaphorically conceived – instead of a force, evil could (outside the strictness frame) be viewed as an effect, eg of ignorance or greed – in which case strength wouldn’t make quite as much sense as a primary moral value.

It’s usually taken for granted that strength is “good” in concrete, physical ways, but we’re talking about metaphor here. Or, rather, we’re thinking metaphorically (mostly without being aware of the fact) – in a way which affects our hierarchy of values. With “strictness” framing, we’ll give higher priority to strength (discipline, control) than to tolerance (fairness, compassion, etc). This may influence everything from our relationships to our politics and how we evaluate our own mental-emotional states.

‘Authoritarian’ moral framing

We’re constrained by ‘social attitudes’ which put moral values in a different order than our own. Moral conflicts aren’t just about “good” vs “bad” – they’re about conflicting hierarchies of values.

For example, you mightn’t regard hard work or self-discipline as the main indicators of a person’s worth – but someone with economic power over you (eg your employer) might. To give an example of how different moral hierarchies lead to conflicting political views, consider welfare. From the ‘progressive’ viewpoint, welfare is generally regarded as morally good – the notion of a social ‘safety net’ appeals to a moral hierarchy in which caring and compassion are primary values. Strict conservatism, on the other hand, tends to view welfare not just as an economic drain, but as immoral. You get a sense of this when it’s framed as “rewarding people for sitting around doing nothing”. Here are the steps in ‘strict’ moral logic which lead to the view that welfare is immoral:

1. “Laziness is bad”. Under ‘strictness’ morality, self-indulgence (eg idleness) is seen as moral weakness, ie emergent evil. It represents a failure to develop the ‘moral strengths’ of self-control and self-discipline (which are primary values in this worldview).

2. “Time-wasting is very bad”. Laziness also implies wasted time according to this viewpoint. So it’s ‘bad’ in the further sense that “time is money”. Inactivity and idleness are seen as inherently costly, a financial loss. People tend to forget that this is metaphorical – there is no literal “loss” – and the frame excludes notions of benefits (or “gains”) resulting from inaction/indolence.

3. “Welfare is very, very bad”. Regarded (by some) as removing the “incentive” to work, welfare is thus seen as promoting moral weakness (ie laziness, time-wasting, “dependency”, etc). That’s bad enough in itself (from the perspective of Strictness Morality) – but, in addition, welfare is usually funded by taxing those who work. In other words, the “moral strength” of holding a job isn’t being rewarded in full – it’s being taxed to reward the “undeserving weak”.

3. “Welfare is very, very bad”. Regarded (by some) as removing the “incentive” to work, welfare is thus seen as promoting moral weakness (ie laziness, time-wasting, “dependency”, etc). That’s bad enough in itself (from the perspective of Strictness Morality) – but, in addition, welfare is usually funded by taxing those who work. In other words, the “moral strength” of holding a job isn’t being rewarded in full – it’s being taxed to reward the “undeserving weak”.

Thus welfare is seen as doubly immoral in this system of moral metaphors. (Donald Trump uses typical ‘strict father’ framing on the issue of welfare. He believes that benefits discourage people from working: “People don’t have an incentive,” he said to Sean Hannity during his campaign. “They make more money by sitting there doing nothing than they make if they have a job.”).

“Might is right”

In ‘strict father’ morality, one must fight evil (and never “understand” or tolerate it). This requires strength and toughness and, perhaps, extreme measures. Merciless enforcement of might is often regarded as ‘morally justified’ in this system. Moral “relativism” is viewed as immoral, since it “appeases” the forces of evil by affording them their own “truth”.

“We don’t negotiate with terrorists… I think you have to destroy them. It’s the only way to deal with them.” (Dick Cheney, former US Vice President)

There’s another sense in which “might” (or power) is seen as not only justified (eg in fighting evil) but also as implicitly good: Strictness Morality regards a “natural” hierarchy of power as moral, and in this conservative moral system, the following hierarchy is (according to Lakoff’s research) regarded as truly “natural”: “God above humans”; “humans above animals”; “men above women”; “adults above children”, etc.

So, the notion of ‘Moral Authority’ arises from a power hierarchy which is believed to be “natural” (as in: “the natural order of things”). Lakoff comments:

“The consequences of the metaphor of Moral Order are enormous, even outside religion. It legitimates a certain class of existing power relations as being natural and therefore moral, and thus makes social movements like feminism appear unnatural and therefore counter to the moral order.” (George Lakoff, Moral Politics, p82)

In this metaphorical reality-tunnel, the rich have “moral authority” over the poor. The reasoning is as follows: Success in a competitive world comes from the “moral strengths” of self-discipline and self-reliance – in working hard at developing your abilities, etc. Lack of success, in this worldview, implies not enough self-discipline, ie moral weakness. Thus, the “successful” (ie the rich) are seen as higher in the moral order – as disciplined and hard-working enough to “succeed”.

‘Erosion of values’ & ‘moral purity’

Media hysteria sometimes calms down a little. But it only takes one horrible crime or indication of ‘Un-American’ behaviour (etc) to set it off again. Then we have: “erosion of values”, “tears in the moral fabric”, a “chipping away” at moral “foundations”, “moral decay”, etc. It shouldn’t be surprising that these metaphors for change-as-destruction tend to accompany ‘conservative’ moral viewpoints rather than ‘progressive’ ones.

Associated with moral ‘decay’ is the metaphor of impurity, ie rot, corruption or filth. This extends further, to the metaphor of morality as health. Thus, immoral ideas are described as “sick“, immoral people are seen to have “diseased minds”, etc. These metaphorical frames have the following consequences in terms of how we think:

1. Even minor immorality is seen as a major threat (since introduction of just a tiny amount of “corrupt” substance can taint the whole supply – think of water reservoir or blood supply. This is applied to the abstract moral realm via conceptual metaphor.)

2. Immorality is regarded as “contagious”. Thus, immoral ideas must be avoided or censored, and immoral people must be isolated or removed, forcibly if necessary. Otherwise they’ll “infect” the morally healthy/strong. Does this way of thinking sound familiar? (This framing has taken scaremongering forms in the Brexit and Trump campaigns).

In Philosophy in the Flesh, Johnson & Lakoff point out that with “health” as metaphor for moral well-being, immorality is framed as sickness and disease, with important consequences for public debate:

“One crucial consequence of this metaphor is that immorality, as moral disease, is a plague that, if left unchecked, can spread throughout society, infecting everyone. This requires strong measures of moral hygiene, such as quarantine and strict observance of measures to ensure moral purity. Since diseases can spread through contact, it follows that immoral people must be kept away from moral people, lest they become immoral, too. This logic often underlies guilt-by-association arguments, and it often plays a role in the logic behind urban flight, segregated neighborhoods, and strong sentencing guidelines even for nonviolent offenders.”

Enemies everywhere, everything a threat

There’s a lot to fear from the perspective of ‘strictness morality’: the world’s a dangerous place, there’s immorality and “evil” lurking everywhere – an ever-present threat from the “foreign” and “alien”. And any weakness that you manifest will be punished. Even the good, decent people are competing ruthlessly with you, judging you for any failure.

In a way, this moral framing logically requires that the world is seen as essentially dangerous. Remove this premise and strictness morality ‘collapses’, since the precedence given (in this scheme) to moral strength, self-discipline and authority (over compassion, fairness, happiness, etc) would no longer make sense.

Rightwing media (tabloid newspapers, Fox News, etc) appear to have the function of reinforcing the fearful premise with daily scaremongering – presumably because it’s more profitable than less dramatic “news”. But this repeated stimulation of our fears affects us at a synaptic level. The fear/alarm framing receives continual reinforcement, triggering the ‘strict father’ worldview, making the model more active, more dominant in our brains.

Update (23/1/2017) – see George Lakoff’s comments on Trump’s inaugural speech. Lakoff says “Trump is a textbook example of Strict Father Morality”, but he also gives some clues on Trump’s weaknesses and how to defeat him (for example, Trump is already a “betrayer of trust” – seen as a big sin in strict father morality).

Media-free zones – avoiding toxic “news”

April 25, 2013

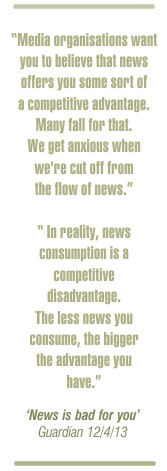

I wrote this in the 1990s (for a magazine). I’m resurrecting it here for two reasons – 1) a recent Guardian article (News is bad for you) makes similar points, and, 2) I’ve had my fill of “news” lately, and plan to practise what I preach here…

“Information anxiety” is caused by the “ever widening gap between what we understand and what we think we should understand”, according to Saul Wurman, who coined the term. But what makes us think we should understand any of it?

“Information anxiety” is caused by the “ever widening gap between what we understand and what we think we should understand”, according to Saul Wurman, who coined the term. But what makes us think we should understand any of it?

There are two common notions about “being informed”: i) it’s irresponsible not to be, and ii) it’s unsafe not to be. In other words, social consensus (which defines “irresponsible”) and basic survival anxieties (which define “unsafe”) lead to information anxiety – so perhaps it shouldn’t be underestimated as a social influence.

Most people probably feel Oprahfied to some extent – ie pressured to have opinions on everything the media defines as important. And they fear falling behind. (According to a report in the Guardian,1 nearly half the population have this fear).

This is partly due to “good marketing” – the advertisers’ and content-providers’ constant drip, drip of things you “should” know about is intended to induce anxiety, so you spend money to relieve it. (A major UK company’s marketing chief once admitted to me that his profession was concerned entirely with stimulating consumer fear and greed).2

As a selling strategy, “fear of being left out” has no limits when applied to media (entertainment/information-based) products. There’s a limit to how many cars you need, but there’s no limit to what you “should” know about.

…

The info-anxiety theory recommends that we find more effective ways to process information, so we can absorb more without being overwhelmed. A better approach, however, might be to simply filter out the 99.9% of information that serves no purpose for you.

The info-anxiety theory recommends that we find more effective ways to process information, so we can absorb more without being overwhelmed. A better approach, however, might be to simply filter out the 99.9% of information that serves no purpose for you.

How much “information” consists of people making noises to avoid listening to themselves think? Media presenters tend not to be quietly reflective. The over-representation of “loud” personalities on TV no doubt contributes to the increasingly accepted notion that “quiet introspection” is a mental illness – peaceful isolation from extroversion and media noise seems like a difficult commodity to find.

Fortunately, you don’t need a cave to escape to – you can take a holiday from info-noise without going anywhere, simply by changing a few parameters of your mental processes. This technique has existed in various forms for centuries – used by “eccentrics” who wanted to revive their faculty of thinking, as opposed to having people’s thoughts (ie reflection rather than verbal loops).

Side effects included improved imagination and weirder dreams. You might enjoy trying it:

→ For a set period (eg 1 or 2 weeks), completely avoid TV, newspapers, magazines, radio, browsing in newsagents, topical chatter, etc [2013 update: add online news & social media to the list]. This is done by refusing such stimuli any admittance to your mind.

Mass-media “information” largely consists of non-useful, vaguely entertaining distraction. Of the non-trivial, non-amusement content (eg some of “the news”), most concerns things you’re powerless to influence. (Conversely, the issues you might influence seem notably absent).

Why clutter your brain with things you can do nothing about? How can it be irresponsible or unsafe to ignore it, if (at best) it’s of no positive use to you, and (at worse) it damages your health?

2013 addition: The recent Guardian piece I mentioned makes pretty much the same points (plus several others). I recommend a good look at it. Here are a few quotes:

“Thinking requires concentration. Concentration requires uninterrupted time. News pieces are specifically engineered to interrupt you. They are like viruses that steal attention for their own purposes. News makes us shallow thinkers. But it’s worse than that. News severely affects memory.”

“Most news consumers – even if they used to be avid book readers – have lost the ability to absorb lengthy articles or books. After four, five pages they get tired, their concentration vanishes, they become restless. It’s not because they got older or their schedules became more onerous. It’s because the physical structure of their brains has changed.”

(‘News is bad for you’, Guardian, 12/4/13)

Sources:

1. The Guardian, 22/10/96

2. M&SFS Head of Marketing, 1990

Graphics by NewsFrames

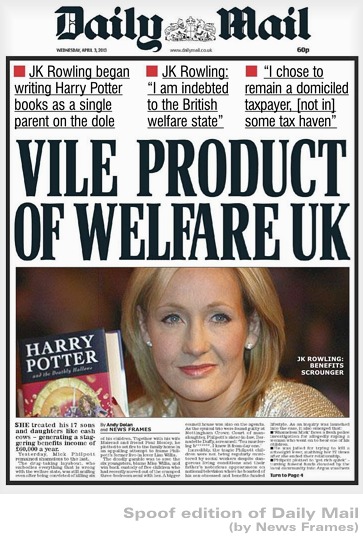

A Daily Mail front page you won’t see…

April 8, 2013 – JK Rowling should perhaps be given a Nobel Prize for getting a generation of kids to read books. As if that wasn’t enough, she’s generated endless amounts of tax revenue. How was this phenomenon nurtured? By a little time and space on the dole.

April 8, 2013 – JK Rowling should perhaps be given a Nobel Prize for getting a generation of kids to read books. As if that wasn’t enough, she’s generated endless amounts of tax revenue. How was this phenomenon nurtured? By a little time and space on the dole.

You’d be surprised how many successful people developed their craft on the dole. In a way, most successful corporations also require a long period on the dole. Do you think Boeing and Microsoft would have achieved commercial success without decades of state-funded research and development in aerospace and computing?

Any true wealth-generating activity requires periods of “social nurturing” which aren’t profitable. They’re not self-funding in the short term; they are dependent. (We realise this for children – we call it “education”. The money spent on it is regarded as social investment).

“Investment” (in human beings) was also one of the ideas – along with “safety net” – behind “social security”. The welfare state was created in the forties, in a post-war economy which was nowhere near as wealthy as now (imagine: computer technology didn’t exist).

But, for decades, the rightwing press, “free market” think-tanks, politicians and pundits (not just of the right) have wanted you to think differently about social security. They want you to think of “welfare” as an unnecessary nuisance which costs more than everything else combined.

To that end, a simple set of claims, accompanied by a certain type of framing, is relentlessly pushed into our brains by newspaper front pages and TV and internet screens. It has two main components:

- Vastly exaggerate the real cost of “welfare” and falsely portray it as “spiralling out of control” (how this is done is explained here and here). Misleadingly include things like pensions in the total cost when you’re talking about unemployment. (This partly explains why people believe unemployment accounts for 41% of the “welfare” bill, when it accounts for only 3% of the total).

- Appeal to the worst aspects of social psychology by repeatedly associating a stereotype (the “benefits scrounger/cheat”) with the concept of “welfare”. One doesn’t have to be a prison psychologist to understand how anger and frustration are channeled towards those perceived as lower in the pecking order: “the scum”. (According to a recent poll, people believe the welfare fraud rate is 27%, whereas the government estimates it as 0.7%).

It’s a potently malign cocktail. When imbibed repeatedly, there’s little defense against its effects. Even those who depend on benefits come to view benefits recipients in a harshly negative light (see Fern Brady’s article for examples). Those politicians who aren’t naturally aligned with rightwing ideology go on the defensive – they talk about “being tough” and “full employment“. It just reinforces the anti-welfare framing.

The strangely puritanical – and deeply irrational – obsession with “jobs”, “hard-working families”, etc, at a time in history when greater leisure for all is more than a utopian promise (due to the maturation of labour-saving technology, etc) seems an integral part of the conservative framing – which is perhaps why many on the “left” find it difficult to provide counter-narratives.

But that would require another article. For now I’ll leave you with a short video explaining Basic Income – a fast-spreading idea which is highly relevant to the above. (Guardian columnist George Monbiot recently championed Basic Income as a “big idea” to unite the left).

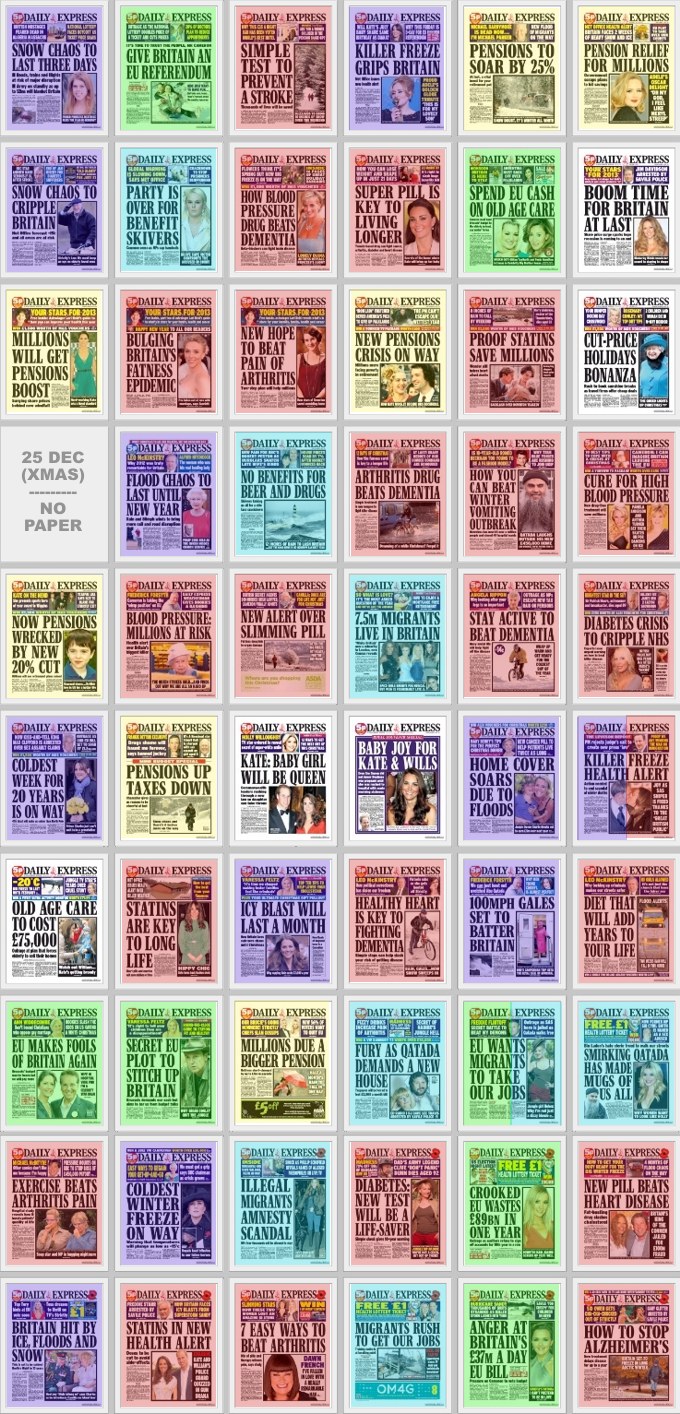

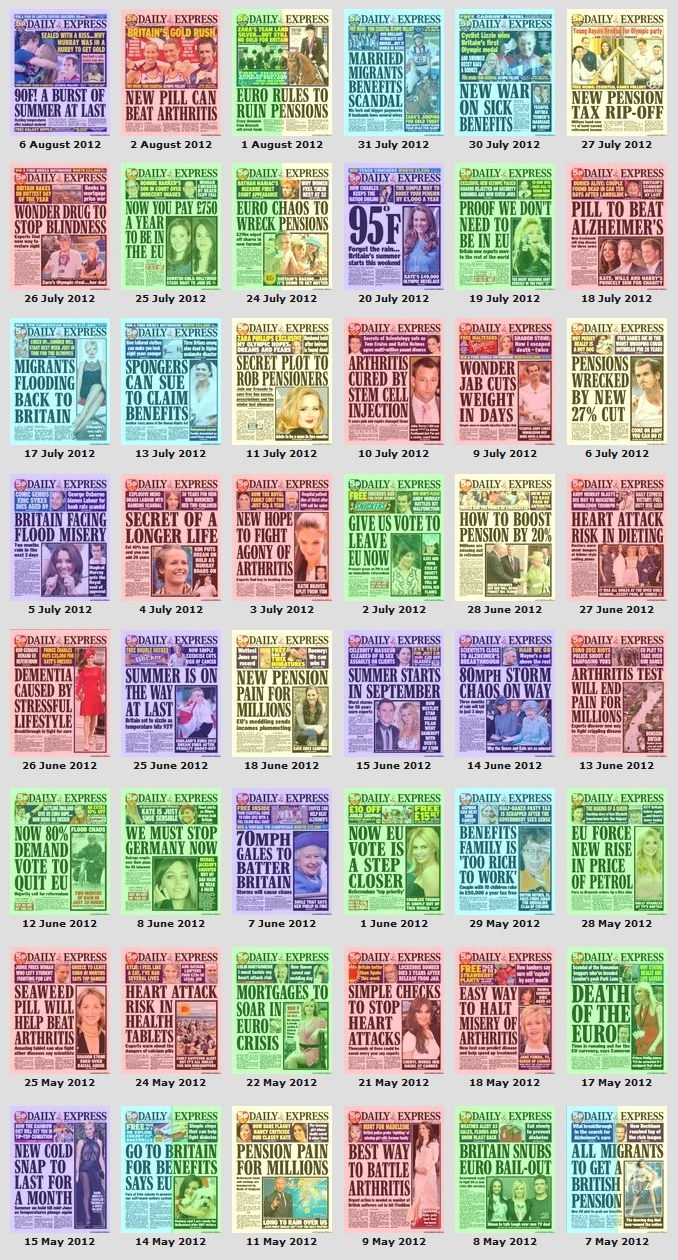

Curious repeating headlines in the Daily Express

Jan 24, 2013 – You’ve probably noticed the Daily Express headlines which feature the weather or some health-related story. It seems that most Express headlines fall into one of these categories:

Jan 24, 2013 – You’ve probably noticed the Daily Express headlines which feature the weather or some health-related story. It seems that most Express headlines fall into one of these categories:

1. Weather/floods

2. Health/illness

3. The EU/Euro

4. Pensions

5. “Migrants”, benefits, “skivers”

Exceptions seem uncommon. Okay, you get the occasional “royals” story, and there was a time when house-price rises/falls could have been added to the list. See for yourself, using the compilations of front pages, below (which I’ve colour-coded to match the above categories).

Occasionally, two of the topics are combined in one headline (see example, above left – “ALL MIGRANTS TO GET A BRITISH PENSION”).

The first collection of front pages shows every Daily Express from 18 January 2013 (top left) back to 29 October 2012 (bottom right), with all exceptions shown (uncoloured):

The latest circulation figures show the Express selling many more copies than the Times, Guardian and Independent (roughly the same number as the Telegraph, and fewer than the Sun and Daily Mail).

The next compilation of Express front pages covers the period from early August 2012 (top left) back to May 2012 (bottom right) – it’s not a complete list, and excludes some exceptions as well as other examples which conform to the above topics:

UPDATE:

Several months after I posted the above article, Press Gazette ran a similar piece titled: ‘Groundhog day: Why Daily Express front pages may leave readers with a sense of deja vu’ (August 7, 2013). It has a different selection of examples of Daily Express front pages than mine (more on the health and weather themes, and some from the period when house prices was a constant headline subject). Here’s the link to it.

Anxiety-inducing frames

This is an updated (& much rewritten) version of an article published by the Guardian in 1999,

which I originally wrote for the Idler magazine.

In every job interview I’ve had, I’ve struggled to give the (false) impression that I was applying out of free choice & enthusiasm (rather than financial dilemma & survival anxiety). Telling the truth rarely helps in these matters, and most interviewers wouldn’t want to hear it.

In every job interview I’ve had, I’ve struggled to give the (false) impression that I was applying out of free choice & enthusiasm (rather than financial dilemma & survival anxiety). Telling the truth rarely helps in these matters, and most interviewers wouldn’t want to hear it.

Financial anxiety turns most of us into useful idiots. In the everyday world of tedious wage slavery, useful idiots can be identified by their claim to like their jobs (I don’t mean the lucky few who really love their jobs). When so many people seem to “enjoy” being economic slaves, or at least pretend to, one suspects something beyond deluded sentimentality – something sinister and pathological.

We’re living in an anxiety culture and we’re driven by fear. For 1 in 7 people, it’s of clinical severity (15% of people in England suffer from an anxiety-related mental disorder). A Mental Health Foundation report (2009) found that 77% of people say they are more frightened than they used to be, and 66% have fear/anxiety about the “current financial situation”.1

The MHF report criticises politicians, public bodies, businesses and the media for what it calls “institutionally-driven fear”, fuelled by scaremongering use of “most calamitous scenarios” on issues such as crime, terrorism, the economy, etc. (Incidentally, I was amused to see that the MHF report cited my 1999 Guardian article* as a source for: “60% of employees suffer from feelings of insecurity and anxiety, with 43 % having difficulty sleeping because of work worries” – a finding I’d quoted from a 1995 ITV documentary, World in Action).

Yuppies-in-adverts redux

The picture that emerges seems at odds with the grinning, self-assured yuppie reality beamed into our living rooms during commercial breaks. It’s a cliché, but advertisers still present a world where “normal” people smile perpetually while driving their expensive new cars. The result is that we feel abnormal and humiliated driving old cars or taking buses. No one is immune from these social-comparison anxieties, not even the marketers themselves (surveys show advertising executives to be “plagued by self-doubt and insecurity”2).

There are strong vested interests in keeping public anxiety at a high level. Anxious people make good consumers – they tend to eat/drink compulsively, need more distractions (newspapers, TV, etc) and more buttressing of their fragile self-image through “lifestyle” products. The financial services industry (insurance, savings, etc) makes billions from our financial insecurities. The unsubtle targeting of our fears is evident in adverts for everything from vehicle recovery services and private health care to chewing gum and mouthwash.

Employers benefit if workers fear losing their jobs – fearful people are less likely to complain, and tend to be more suggestible and compliant. Politicians cite “public fears” as justification for freedom-eroding legislation; insecure populations show a tendency to favour the authoritarian rhetoric of “strong leaders”. In a word, governments and corporations gladly reap the harvests of high public anxiety.

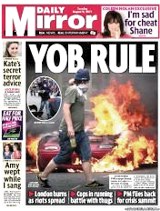

The Daily Scare

According to the Mental Health Foundation report, 60% of those who think that “people are becoming more anxious or frightened” blame it partly on “the impact of the media”. Anxiety can be induced in a population by constantly focusing on the threat of things like crime and terrorism in an exaggerated way. (I wrote the article before the financial collapse; it’s possible that with an emphasis on economic perils, crime isn’t currently hyped so much).

In a MORI poll conducted in the early 1990s, half of those questioned believed that tabloid newspapers have a vested interest in making people more afraid of crime. In 1995, the makers of Frontline, a Channel 4 documentary on crime, requested interviews with the editors of the Daily Mail, Mirror, Sun, Daily and Sunday Express, Today, People and Star, to ask how they justified their sensationalised crime coverage. They all refused to be interviewed.3

In a MORI poll conducted in the early 1990s, half of those questioned believed that tabloid newspapers have a vested interest in making people more afraid of crime. In 1995, the makers of Frontline, a Channel 4 documentary on crime, requested interviews with the editors of the Daily Mail, Mirror, Sun, Daily and Sunday Express, Today, People and Star, to ask how they justified their sensationalised crime coverage. They all refused to be interviewed.3

Unfortunately, many people believe the crime hype (belief seems to correlate with acceptance of the conservative “moral breakdown” framing). A third of elderly women fear going outside their homes, but only one in 4,000 will be assaulted.4 Statistically, the elderly and young children are the groups least at risk from attack – but because newspapers repeatedly cover crimes victimising the vulnerable, they seem more common than they are.

One effect of our over-stimulated fears is widespread paranoia. Consider this news item from the Independent newspaper: “Teachers have been warned not to put sun cream on young pupils because they could be accused of child abuse”. These warnings were then criticised by cancer charities. Skin-cancer risk versus child-abuse accusation risk. Welcome to Anxiety Society.

Most fear/worry results from what we’ve been thinking rather than external events. We’re immersed in anxiety-inducing belief systems which we regard as perfectly normal. Exposure to these fearful worldviews starts in early childhood, before we’ve developed intellectual defences, and it continues in school, where we learn to be obedient, economically-frightened grown-ups.

Anxiety-inducers

“Fear triggers the strict father model; it tends

“Fear triggers the strict father model; it tends

to make the model active in one’s brain”5

— George Lakoff

One of the most insidious anxiety-inducers is a sort of secular equivalent of “original sin” – the belief that, in essence, you’re “lacking” or “not good enough” and must redeem yourself with hard work and suffering. This “no pain, no gain” worldview manifests as the idea that you’re infinitely undeserving – that reward, ie happiness, will always be contingent upon the endurance of unpleasant activity (eg work).

It makes life seem a burden rather than an adventure, it’s exploited to the maximum by big business, and it makes you feel guilty.

This deep-seated mindset can be subverted with psychological gimmicks. For example, try believing that you deserve to be paid for doing nothing. Dismiss the notion that you have to “earn” anything. You earned your life by being born – now you deserve to relax. Quit your job and go on holiday, or call in sick as often as possible. Remove all forms of guilt from your mind. Go to extremes of laziness and indulge yourself deluxe-style every day. (When re-reading this paragraph, it seemed almost “blasphemous” in the current austere climate. I originally intended it as partly serious, partly ironic).

‘False responsibility’ framing

Another insidious anxiety-inducer to watch out for is the belief that you should be responsible. This puts people under tremendous strain. You don’t choose your genetic makeup or the conditions in which you grow up, yet all the unfortunate things that happen are supposed to be your fault.

In most cases, the de facto function of “individual responsibility” is social conformity. Society holds you accountable if you don’t comply with its definition of your responsibilities. The attraction of “responsibility” is that it allows people total conformity without removing the facade of heroic individuality – it’s the kind of concept that advertisers dream about.

This “responsibility” tends to see everything as a problem needing a solution – usually involving endless work. Pushed too far, it undermines progress towards desirable conditions such as increased leisure. Intelligent attempts to drastically cut average working hours, for example, are resisted on the basis that it’s irresponsible. (Similar, perhaps, to the Puritanism that H.L. Mencken described as “The haunting fear that someone, somewhere, may be happy”).

Sometimes it might make more sense to pay people to stay at home – as Buckminster Fuller noted when attempting to quantify the amount of fossil fuel we burn whilst travelling to pointless jobs. But politicians – the experts on responsibility – see joblessness as the ultimate irresponsible lifestyle. It never occurs to them that their idea of responsibility might not be universal.

Sometimes it might make more sense to pay people to stay at home – as Buckminster Fuller noted when attempting to quantify the amount of fossil fuel we burn whilst travelling to pointless jobs. But politicians – the experts on responsibility – see joblessness as the ultimate irresponsible lifestyle. It never occurs to them that their idea of responsibility might not be universal.

Thus, a real and massive problem – how to distribute wealth humanely in a wealthy technological (ie automated) society – becomes as unsolvable as the mythical “moral breakdown” when it’s framed in terms of jobs & joblessness (with all the social anxieties that this framing triggers).

“Fear triggers the strict father model”. In Lakoff’s terminology, the “strict father model” refers to the deep cognitive frames which form the moral worldview of rightwing “conservatives”. In effect he is saying that people tend to think in more conservative (and less progressive) terms to the extent that they are being frightened.

Footnotes

*My original Guardian article was published on 8 October, 1999, in the Guardian’s ‘Editor’ pull-out supplement. The text is available online here.

1. The Mental Health Foundation’s April 2009 report, titled In the Face of Fear, which “reveals a UK society that is increasingly fearful and anxious”.

2. Quoted from The Times, 22 November 1996.

3. Frontline, Channel 4, 4 October 1995.

4. Sunday Times, 6 August 1995.

5. Lakoff, Don’t think of an elephant, page 42.

Stupid economic metaphors

Sept 23, 2011 – Today’s Daily Mail headline uses David Cameron’s ‘economics-as-shotgun’ metaphor. ‘i’ goes with “Global slump” – as if everyone on the planet simultaneously collapsed onto the sofa.

Sept 23, 2011 – Today’s Daily Mail headline uses David Cameron’s ‘economics-as-shotgun’ metaphor. ‘i’ goes with “Global slump” – as if everyone on the planet simultaneously collapsed onto the sofa.

On last night’s Question Time (BBC1), Vince Cable talked about the economy with the phrases “on a tightrope” (twice), and “very dangerous world” (twice). By “world” he meant the abstraction known as the “global economy”.

An audience member on Question Time queried the premise that economic “growth” was necessary. Harriet Harman responded by saying the deficit can’t be cut “if the economy is flatlining”. She didn’t expand on this. So, we have the “growth” metaphor answered with a medical metaphor (for clinical death). Is it surprising that people are confused about economics?

Of course, we need abstractions and metaphors in order to discuss conceptually-complex issues. But what’s evident from last night’s Question Time, and this morning’s newspaper coverage, is that very little but a series of vague, conflicting economic metaphors (representing “conventional wisdom”) gets spoken. Meanwhile, what are we to make of the claim of expert economist, Professor Paul Ormerod, that: “as the twentieth century draws to a close the dominant tendency in economic policy is still governed by a system of analysis inspired by the engineers and scientists of the Victorian era”. (Ormerod, The Death of Economics).

Ormerod explains how a Victorian metaphorical worldview underlies the model of competitive equilibrium which provides much of the rationale for implementing “free-market solutions” to all economic “problems” (an ideological approach which has been dominant in the UK and US since the early 1980s).

One gets the sense that it’s the map, rather than the territory, which is fucked (or “flatlining” or on a tightrope, or staring down a gun-barrel, etc) in the case of economics. And that, in itself, can lead to unfortunate (or even tragic) consequences for the territory.

Meanwhile, the world still has pretty much all the stuff it had last month. And there hasn’t been any sudden global population explosion in the past few weeks. And valid questions on real resources, environmental issues, etc, tend to be framed separately from the “economic crisis” – in “public” (ie media/political) debate at least – compartmentalisation and specialisation.

Alternative headlines:

• ‘ECONOMY HAS BOILS & SMELLS BAD’

• ‘GROWTH LEADS TO OBESE ECONOMY’

• ‘RISING HEMLINES STIMULATE ECONOMY’

“Scrounging families”

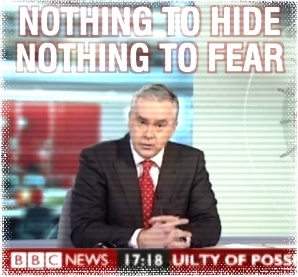

Sept 2, 2011 – The BBC reports this story under the headline, ‘NUMBER OF WORKLESS HOUSEHOLDS FALLS’. The Express goes with “SCROUNGING FAMILIES’, “anger” and “fury” – and again quotes the rightwing pressure group, the TaxPayers’ Alliance (a regular source of framing for the UK press).

Sept 2, 2011 – The BBC reports this story under the headline, ‘NUMBER OF WORKLESS HOUSEHOLDS FALLS’. The Express goes with “SCROUNGING FAMILIES’, “anger” and “fury” – and again quotes the rightwing pressure group, the TaxPayers’ Alliance (a regular source of framing for the UK press).

Here’s the first paragraph on the Express’s front page (2/9/11):

“ANGER at the scale of Britain’s benefits culture erupted last night after official figures showed there are nearly four million households where no one works.”

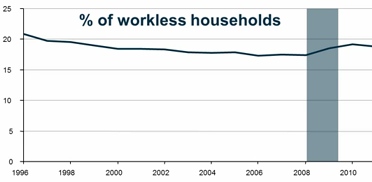

So, “anger erupted” at these official figures (from the Office for National Statistics, ONS). Whose anger erupted? Here’s what the ONS figures actually show (courtesy of an ONS graph):

Note the fall in “workless households” since 1996, followed by an increase coinciding exactly with the recent recession (shaded bar).

Perhaps “anger erupted” over something else. The fourth paragraph on the Express front page says: “The figures yesterday triggered renewed fury at the £180billion annual welfare benefits bill being picked up by taxpayers.”

This is the standard, misleading device of citing the total welfare bill in a story about the unemployed. It’s misleading because only a small fraction of this amount goes on unemployment benefits (£6.6bn directly in 2010; two-thirds of the total welfare figure goes on people over working age, and there are various benefits for those who have jobs, and contribution-based benefits that need to be taken into account, etc).

The welfare-as-crime frame

The Express front page talks of “the culture of benefits dependency that was allowed to spiral out of control under the previous Labour government.” The spiralling “out of control” of an immoral “culture” evokes the crime frame. Politicians and media often use a “criminal offender” type of lexicon to talk about welfare recipients. This tendency seems to go back a few decades at least, although I suspect media analysis would show it to be increasing in recent years (in the same way that use of terms such as “benefit cheats” has increased). Thus, government advisers were quoted by the Times (17/9/99) as saying that “penalties for the persistent unemployed will be harsher”. Terms such as “hardcore” are applied to “persistent” unemployed. Benefits are being framed as a moral issue – this is how “anger” and “fury” are induced, via moral outrage. The implication is that punishment is the cure (and that, therefore, people shouldn’t complain about getting their benefits cut).

(Updates: a later Daily Express headline used a different type of welfare-crime association: “1.2M CRIMINALS GET BENEFITS”. Also, Tony Blair used the odd phrase “hard core of socially excluded families”).

“Spiralling out of control”?

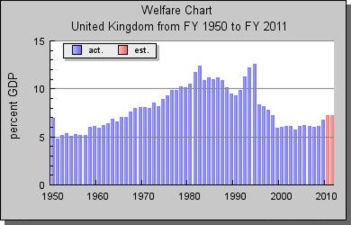

Back to reality (or at least to statistical representations of it). We should be looking at welfare spending as a proportion of GDP, not in “absolute” terms:

This chart is taken from the excellent UK Public Spending website. There doesn’t seem to be any reason for “fury” here. Perhaps the Daily Express editors need to take an anger management course? And perhaps they should stop acting as a propaganda outlet for the rightwing TaxPayers’ Alliance group…

This chart is taken from the excellent UK Public Spending website. There doesn’t seem to be any reason for “fury” here. Perhaps the Daily Express editors need to take an anger management course? And perhaps they should stop acting as a propaganda outlet for the rightwing TaxPayers’ Alliance group…

Alternative headlines:

• ‘ANGRY FOR THE WRONG REASONS’

• ‘TAXPAYERS ALLIANCE PRESS RELEASE No.94’

• ‘LYING BASTARDS WROTE THIS HEADLINE’

This is a longish intro to the topic of framing – based on key themes in the work of cognitive scientist

This is a longish intro to the topic of framing – based on key themes in the work of cognitive scientist  The “time is money” frame has certain negative consequences (stress, insecurity, short-termism, etc) – in addition to the positive things claimed for it by business managers and orthodox economists. In fact, most anxiety seems to result from how we metaphorically conceive of our projected future. More on this later.

The “time is money” frame has certain negative consequences (stress, insecurity, short-termism, etc) – in addition to the positive things claimed for it by business managers and orthodox economists. In fact, most anxiety seems to result from how we metaphorically conceive of our projected future. More on this later. There are two common metaphors for work: as obedience and as exchange. In the work-as-obedience frame, there’s an authority (eg the employer) and there’s obedience to the commands of authority (ie work). This obedience is rewarded (pay). In the work-as-exchange frame, work is conceptualised as an object of value which belongs to the worker. This is exchanged for money.

There are two common metaphors for work: as obedience and as exchange. In the work-as-obedience frame, there’s an authority (eg the employer) and there’s obedience to the commands of authority (ie work). This obedience is rewarded (pay). In the work-as-exchange frame, work is conceptualised as an object of value which belongs to the worker. This is exchanged for money. “Fear triggers the strict father model; it tends

“Fear triggers the strict father model; it tends A ‘reward & punishment’ type morality follows from strictness framing. Punishment of disobedience is seen as a moral good – how else will people develop the self-discipline necessary to prosper in a dangerous, competitive environment? Becoming an adult, in this belief-system’s logic, means achieving sufficient self-discipline to free oneself from “dependence” on others (no easy task in a “tough world”). Success is seen as a just reward for the obedience which leads ultimately to self-discipline. Remaining “dependent” is seen as failure.

A ‘reward & punishment’ type morality follows from strictness framing. Punishment of disobedience is seen as a moral good – how else will people develop the self-discipline necessary to prosper in a dangerous, competitive environment? Becoming an adult, in this belief-system’s logic, means achieving sufficient self-discipline to free oneself from “dependence” on others (no easy task in a “tough world”). Success is seen as a just reward for the obedience which leads ultimately to self-discipline. Remaining “dependent” is seen as failure. Central to Strictness Morality is the metaphor of moral strength. “Evil” is framed as a force which must be fought. Weakness implies evil in this worldview, since weakness is unable to resist the force of evil.

Central to Strictness Morality is the metaphor of moral strength. “Evil” is framed as a force which must be fought. Weakness implies evil in this worldview, since weakness is unable to resist the force of evil.

— George W. Bush

— George W. Bush → “Welfare is very, very bad”

→ “Welfare is very, very bad” “We don’t negotiate with terrorists… I think you have to destroy them. It’s the only way to deal with them.”

“We don’t negotiate with terrorists… I think you have to destroy them. It’s the only way to deal with them.”

Media hysteria sometimes calms down a little (eg when the focus is on the decent, respectable people, rather than the bad people**). But it only takes one horrible crime to set it off again. Then we have: “moral decay”, “erosion of values”, “tears in the moral fabric”, a “chipping away” at moral “foundations”, etc. It shouldn’t be surprising that these metaphors for change-as-destruction tend to accompany ‘conservative’ moral viewpoints rather than ‘progressive’ ones.

Media hysteria sometimes calms down a little (eg when the focus is on the decent, respectable people, rather than the bad people**). But it only takes one horrible crime to set it off again. Then we have: “moral decay”, “erosion of values”, “tears in the moral fabric”, a “chipping away” at moral “foundations”, etc. It shouldn’t be surprising that these metaphors for change-as-destruction tend to accompany ‘conservative’ moral viewpoints rather than ‘progressive’ ones. Associated with moral ‘decay’ is the metaphor of impurity, ie rot, corruption or filth. This extends further, to the metaphor of morality as health. Thus, immoral ideas are described as “

Associated with moral ‘decay’ is the metaphor of impurity, ie rot, corruption or filth. This extends further, to the metaphor of morality as health. Thus, immoral ideas are described as “ So, to conclude, there’s a lot to fear from the perspective of ‘Strictness Morality’: the world’s a dangerous place, there’s immorality (and indeed “evil”) all over the place, lurking everywhere, ready to jump out at you. And any weakness that you manifest will be punished. Even the good, decent people are competing ruthlessly with you, judging you for any failure.

So, to conclude, there’s a lot to fear from the perspective of ‘Strictness Morality’: the world’s a dangerous place, there’s immorality (and indeed “evil”) all over the place, lurking everywhere, ready to jump out at you. And any weakness that you manifest will be punished. Even the good, decent people are competing ruthlessly with you, judging you for any failure.