Archive for the ‘George Lakoff’ Category

December 2023 updates – essential reading

Some essential reading, items of interest & updates for Winter.

FrameLab

FrameLab is a website written by George Lakoff and Gil Duran. It has insightful up-to-date commentaries focusing on the U.S. political situation and its media framing. Recent posts include the misappropriation of Orwell’s ideas by some US Republicans and others, Elon Musk’s attempts to use algorithm warfare to shift political discourse rightwards, various ways journalists can combat Trump’s normalisation of lying, etc.

You can choose to read a free or paid subscription version of FrameLab, and there’s a newsletter. (If you get the standard Substack opening page which asks for your email address, you don’t have to supply it – you can click on “no thanks” and still read the website).

Doppelganger

You probably saw this summer’s announcements for Naomi Klein’s new book, Doppelganger. I got a copy as soon as it came out – I’d been intrigued by the previews, particularly where Klein talked of influencers such as Steve Bannon co-opting some major ‘left’ tropes to create a “Mirror World” of dissent (of sorts). This refers to the new wave of “anti-establishment” messaging flooding social media, which self-represents as neither “left” nor “right”, yet typically detours to radical-right positions, often packaged with conspiriologic (on anti-vaccine, Deep State memes, etc).

Quite early on in the book, Doppelganger digresses from the widely previewed topics, thus not giving them the thorough investigation I’d expected. This isn’t really intended as a criticism (although I felt slightly disappointed), since the topics that Naomi moved onto – long sections on child autism, her views on parenting, Zionism, etc – have importance in their own right, and she integrates them into her main theme convincingly.

As it happens, the Guardian published an extended extract of Doppelganger prior to the book’s publication (it’s the preview that led to me getting the book). This is the part of the book that interested me most, and which I wrongly assumed would be investigated in greater detail in the rest of the book. In any case, I rate it as essential reading in its own right, as a long-read article:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/aug/26/naomi-klein-naomi-wolf-conspiracy-theories

2023 book on media framing

I’d already written, back in 2016/17, about the appropriation of “anti-establishment” tropes of dissent by radical ‘rightwing’ commentators in both UK and US (eg here and here, on Brexit and Trump).

My much extended and updated 2023 book, Lazy Person’s Guide to Framing, brings these topics up-to-date, including an analysis of how and why Steve Bannon utilised these old ‘left’ frames for his own far-right political project. (This pre-dates Naomi Klein’s book and uses a slightly different approach – semantic framing and Marshall McLuhan’s tetrad – but draws pretty much the same conclusions as Naomi on the question of what Bannon & Co. seem to be up to).

If you missed the plug for my book (I posted it back in February), check it out!

Btw, old news-frames never die! They just get re-animated like corpses in horror films, or re-heated like yesterday’s food. A recent re-heated example of the economic flatlining frame.

The Coming Wave

A lot has been written about the potentials and threats of AI, of course. The Coming Wave, a new book by Mustafa Suleyman, stands out, for me, for a few reasons. Firstly, the author, a genuine ‘AI insider’ (previously co-founder of DeepMind, and Google’s AI policy & product management VP), considers the possible (and in many cases likely or even inevitable) social and political ramifications of the new wave of technology. How these technologies will radically transform societies at virtually every level – a somewhat more interesting (and urgent) issue than whether the latest chatbot seems human enough to flirt with.

Secondly, he presents the scenarios with wide-ranging knowledge, depth of insight and concern at many of the implications. It all seems very vivid, more-than-plausible and in several cases absolutely terrifying. Which is why the author strongly advocates action now to mitigate and regulate some of these real-dystopian trajectories. Thankfully, it doesn’t all look bleak – the positive potentials of the new wave seem truly marvelous and astounding (as you might expect), and the book takes you there as well.

If you think you already know enough about it – you don’t! This book seems like a good start, and I felt encouraged by the remarkable long list of important and prominent people in multiple fields who have provided an endorsement in the book’s blurb pages. It tells me that at least they seem aware of some of these social/political issues – as we all should be.

Noise

Daniel Kahneman is one of those eminent folks who endorses The Coming Wave. A Nobel-prize winner, famous for his book, Thinking, Fast and Slow (which I’m currently in the middle of re-reading), Kahneman has a new book out, which previously escaped my notice (it was published in 2021): Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment (co-written with Olivier Sibony and Cass Sunstein).

Like dreams and jokes, what we loosely call “cognitive biases” tend to easily get forgotten – unless we make a conscious effort to remember them. I mean, how many heuristics (cognitive shortcuts) from the behavioral science literature can you list off the top of your head? How many common logical fallacies? This is one of the reasons I’m re-reading Thinking, Fast and Slow. The experience seems very much: “Oh, gosh, I’d forgotten all about that!”.

Kahneman also co-edited and abundantly contributed to (with his late colleague Amos Tversky) a book titled Choices, Values, and Frames, which I’ve recently obtained a digital copy of (it’s a collection of somewhat technical articles on decision making, ‘Prospect Theory’, behavioral economics, consumer psychology, etc).

Reading these books, particularly Thinking, Fast and Slow, it strikes me how relevant the ideas – the various cognitive biases described – seem to the everyday presentation (framing) and digestion of “news”. Not only in the ways documented by popular authors such as Rolf Dobelli (and of course George Lakoff), but in the “Mirror World”, where fact-checks get shrugged off as part of The Conspiracy, audience stats trump all other stats, and what Kahneman and Tversky call “System 2” routinely gets its crutches kicked out from under it.

Cost of fixing Britain

This Guardian article, from George Monbiot, makes a good attempt at quantifying the money that needs to be spent to repair Britain’s infrastructure and public services after decades of chronic underfunding and political neglect. Here’s the section on the NHS:

‘Some estimates are well-established. The NHS funding deficit – the cumulative difference between the 4% annual increase a modern health system needs to cope with ageing populations and technological change, and what it has received since 2010 – is £200bn. The current annual increase is 0.1%. Restoring the proper funding increase would start at £7bn a year, while addressing the historic shortfall would be an additional £10bn per year.’

Britain is Broken. What will Fix it? – George Monbiot

Populist right – the mass appeal of “strict father” framing

George Lakoff’s book, Moral Politics, popularised the idea that ‘rightwing’ politics stem from a particular moral worldview, which Lakoff called “strict father framing”. Lakoff’s work unearthed, as it were, the cognitive root of prototypical “conservative” beliefs on a wide range of issues (from gun control to economics, from sex and abortion to war and the death penalty).

George Lakoff’s book, Moral Politics, popularised the idea that ‘rightwing’ politics stem from a particular moral worldview, which Lakoff called “strict father framing”. Lakoff’s work unearthed, as it were, the cognitive root of prototypical “conservative” beliefs on a wide range of issues (from gun control to economics, from sex and abortion to war and the death penalty).

When I first read Moral Politics, it felt like a series of lightbulbs switching on inside my head. This was partly because I’d spent a lot of time modestly satirising ‘rightwing’ media views (eg for my Anxiety Culture zine), and I’d been particularly interested in tabloid newspaper obsessions with “spiralling crime”, “scroungers” and “red tape” obstructions to free-market “competitiveness” and “efficiency”. I didn’t know what united these particular ‘rightwing’ obsessions, but there seemed to be a common mindset behind them. Simply labelling them ‘rightwing’ or ‘conservative’ didn’t tell you what these views had as a common thread.

Lakoff’s cognitive theory seemed incredibly good at explaining and predicting the ways in which these views form – and how they all fit together – on all kinds of unrelated issues. The other side of the theory (nurturant framing), meanwhile, provided insights into my own ‘progressive’ views.

Why the rise of the populist right?

I’ve explained in a previous piece why I tend not to buy the “standard” explanations for the victories of Trump and Brexit. It’s not that mass hardship, inequality and animosity towards “establishment elites” (etc) aren’t factors. It’s just that they don’t account for the mass appeal specifically of populist right (including hard-right) views. Over 60 million Americans voted for a billionaire who has expressed beliefs ranging from the ominously authoritarian to the violently fascist. This didn’t happen by default.

Before Brexit, in 2015, the Conservatives were voted back into UK government after years of painful economic austerity instituted by… the Conservatives. At the time, the Guardian’s Roy Greenslade documented how the rightwing press had “played a significant role in the Tory victory”. Although never expressed in the following terms, the role they played was to put a nationalist variant of “strict father” framing all over their front pages, regularly, on issues such as immigration, “stolen” jobs/benefits and interfering foreigners (eg EU bureaucrats). Meanwhile, Barack Obama said part of Trump’s success was down to “Fox News in every bar and restaurant in big chunks of the country”.

But beyond documenting mass discontent with the status quo and stating that the ‘rightwing’ media played a role, what else…?

No ‘leftwing’ model to explain ‘rightwing’ mass appeal?

For obvious reasons, most ‘left’/’liberal’ commentators don’t want to talk in terms of the “ignorance” or “stupidity” of the masses. They also don’t want to portray the majority as bigots (or “deplorables”), or patronisingly assert that the gullible public has been “brainwashed”. So what does that leave?

Most of the explanations I’ve read have simply concentrated on blaming “the liberal media”, the greed and aloofness of establishment elites, the failures of the Democratic campaign, the “liberal media”, the unpopularity of Hillary Clinton and the “liberal” media.

Did I mention “the liberal media”? I’m not even sure what that term commonly refers to anymore. Obviously something homogeneous and bad. Trump supporters, the ‘alt-right’, Corbynistas and the ‘radical’ left all seem to agree on the fungible awfulness of “the liberal media”.

But none of this explains the mass appeal of a specifically hard-right alternative (the 60+ million who voted for an Infowars-style bigot presumably counts as “mass appeal”). For that we need something else. Lakoff’s Moral Politics offers the best model that I’ve seen, to date, for understanding this phenomenon – and it has the advantage of being rooted in cognitive science. Even better, it gives us precise keys to understanding political language as well as worldviews. And it doesn’t require any postulating of mass stupidity, immorality or inherent bigotry in order to account for the mass appeal of hardline rightwing views of the type that Trump and his circle espouse.

I think the “strict father” frame thesis provides important clues to what is happening right now – crucial for the ‘progressive’ ‘left’ to understand. If you don’t have time to read Lakoff’s Moral Politics (or his shorter Don’t Think of an Elephant!), here’s my summary of how the “strict father” frame fits together. I’ve kept it non-technical and left out the jargony cognitive linguistics – it just gives an outline, a flavour of the frame itself…

The “strict father” frame

“Fear triggers the strict father model; it tends to make the model active in one’s brain.”

– George Lakoff, ‘Don’t think of an elephant’, p42

Lakoff makes the case that conservative moral values are based on a “strict father” upbringing model, and liberal (or ‘progressive’) values on a “nurturant parent” model. We all seem to have both models in our brains – even the most “liberal” person can understand a John Wayne film (Lakoff uses Arnold Schwarzenegger movies as examples of the ‘strictness’ moral system).

In the ‘strict father’ moral frame, the world is regarded as fundamentally dangerous and competitive. Good and bad are seen as absolutes, but children aren’t born good – they have to be made good through upbringing. This requires that they are obedient to a moral authority. Obedience is taught through punishment, which, according to this belief-system, helps children develop the self-discipline necessary to avoid doing wrong. Self-discipline is also needed for prosperity in a dangerous, competitive world. It follows, in this worldview, that people who prosper financially are self-disciplined and therefore morally good.

This framing complements, in obvious ways, the ideology of “free market” capitalism. For example, in the latter, the successful pursuit of self-interest in a competitive world is seen as a moral good since it benefits all via the “invisible hand” of the market. In both cases do-gooders are viewed as interfering with what is right – their “helpfulness” is seen as something which makes people dependent rather than self-disciplined. It’s also seen as an interference in the market optimisation of the benefits of self-interest.

Strictness Morality & competition

A ‘reward & punishment’ type morality follows from strictness framing. Punishment of disobedience is seen as a moral good – how else will people develop the self-discipline necessary to prosper in a dangerous, competitive environment? Becoming an adult, in this belief-system’s logic, means achieving sufficient self-discipline to free oneself from “dependence” on others (no easy task in a “tough world”). Success is seen as a just reward for the obedience which leads ultimately to self-discipline. Remaining “dependent” is seen as failure.

Competition is an important premise of Strictness Morality. By competing in a tough world, people demonstrate a self-discipline deserving of reward, ie success. Conversely, it’s seen as immoral to reward those who haven’t earned it through competition. By this logic, competition is seen as morally necessary: without it there’s no motivation to become the right kind of person – ie self-disciplined and obedient to authority. Constraints on competition (eg social “hand-outs”) are therefore seen as immoral.

‘Nurturant’ framing doesn’t give competition the same moral priority. ‘Progressive’ morality tends to view economic competition as creating more losers than winners, with the resulting inequality correlating with social ills such as crime, deprivation and all the things you hope won’t happen to you. The nurturant ideal of abundance for all (eg achieved through technological advance) works against the primacy of competition. Economic competition still has an important place, but as a limited (and fallible) means to achieving abundance, rather than as a moral imperative.

While nurturant morality is troubled by the fear of “not enough to go around for all”, strictness morality is haunted by the fear of personal failure, individual weakness. Even the “successful” seem haunted by this fear.

‘Moral strength’

Central to Strictness Morality is the metaphor of moral strength. “Evil” is framed as a force which must be fought. Weakness implies evil in this worldview, since weakness is unable to resist the force of evil.

People are not born strong, the logic goes; strength is built through learning self-discipline and self-denial – these are primary values in the strictness system, so any sign of weakness is a source of anxiety, and fear itself is perceived as a further weakness (one to be denied at all costs). Note that these views are all metaphorically conceived – instead of a force, evil could (outside the strictness frame) be viewed as an effect, eg of ignorance or greed – in which case strength wouldn’t make quite as much sense as a primary moral value.

It’s usually taken for granted that strength is “good” in concrete, physical ways, but we’re talking about metaphor here. Or, rather, we’re thinking metaphorically (mostly without being aware of the fact) – in a way which affects our hierarchy of values. With “strictness” framing, we’ll give higher priority to strength (discipline, control) than to tolerance (fairness, compassion, etc). This may influence everything from our relationships to our politics and how we evaluate our own mental-emotional states.

‘Authoritarian’ moral framing

We’re constrained by ‘social attitudes’ which put moral values in a different order than our own. Moral conflicts aren’t just about “good” vs “bad” – they’re about conflicting hierarchies of values.

For example, you mightn’t regard hard work or self-discipline as the main indicators of a person’s worth – but someone with economic power over you (eg your employer) might. To give an example of how different moral hierarchies lead to conflicting political views, consider welfare. From the ‘progressive’ viewpoint, welfare is generally regarded as morally good – the notion of a social ‘safety net’ appeals to a moral hierarchy in which caring and compassion are primary values. Strict conservatism, on the other hand, tends to view welfare not just as an economic drain, but as immoral. You get a sense of this when it’s framed as “rewarding people for sitting around doing nothing”. Here are the steps in ‘strict’ moral logic which lead to the view that welfare is immoral:

1. “Laziness is bad”. Under ‘strictness’ morality, self-indulgence (eg idleness) is seen as moral weakness, ie emergent evil. It represents a failure to develop the ‘moral strengths’ of self-control and self-discipline (which are primary values in this worldview).

2. “Time-wasting is very bad”. Laziness also implies wasted time according to this viewpoint. So it’s ‘bad’ in the further sense that “time is money”. Inactivity and idleness are seen as inherently costly, a financial loss. People tend to forget that this is metaphorical – there is no literal “loss” – and the frame excludes notions of benefits (or “gains”) resulting from inaction/indolence.

3. “Welfare is very, very bad”. Regarded (by some) as removing the “incentive” to work, welfare is thus seen as promoting moral weakness (ie laziness, time-wasting, “dependency”, etc). That’s bad enough in itself (from the perspective of Strictness Morality) – but, in addition, welfare is usually funded by taxing those who work. In other words, the “moral strength” of holding a job isn’t being rewarded in full – it’s being taxed to reward the “undeserving weak”.

3. “Welfare is very, very bad”. Regarded (by some) as removing the “incentive” to work, welfare is thus seen as promoting moral weakness (ie laziness, time-wasting, “dependency”, etc). That’s bad enough in itself (from the perspective of Strictness Morality) – but, in addition, welfare is usually funded by taxing those who work. In other words, the “moral strength” of holding a job isn’t being rewarded in full – it’s being taxed to reward the “undeserving weak”.

Thus welfare is seen as doubly immoral in this system of moral metaphors. (Donald Trump uses typical ‘strict father’ framing on the issue of welfare. He believes that benefits discourage people from working: “People don’t have an incentive,” he said to Sean Hannity during his campaign. “They make more money by sitting there doing nothing than they make if they have a job.”).

“Might is right”

In ‘strict father’ morality, one must fight evil (and never “understand” or tolerate it). This requires strength and toughness and, perhaps, extreme measures. Merciless enforcement of might is often regarded as ‘morally justified’ in this system. Moral “relativism” is viewed as immoral, since it “appeases” the forces of evil by affording them their own “truth”.

“We don’t negotiate with terrorists… I think you have to destroy them. It’s the only way to deal with them.” (Dick Cheney, former US Vice President)

There’s another sense in which “might” (or power) is seen as not only justified (eg in fighting evil) but also as implicitly good: Strictness Morality regards a “natural” hierarchy of power as moral, and in this conservative moral system, the following hierarchy is (according to Lakoff’s research) regarded as truly “natural”: “God above humans”; “humans above animals”; “men above women”; “adults above children”, etc.

So, the notion of ‘Moral Authority’ arises from a power hierarchy which is believed to be “natural” (as in: “the natural order of things”). Lakoff comments:

“The consequences of the metaphor of Moral Order are enormous, even outside religion. It legitimates a certain class of existing power relations as being natural and therefore moral, and thus makes social movements like feminism appear unnatural and therefore counter to the moral order.” (George Lakoff, Moral Politics, p82)

In this metaphorical reality-tunnel, the rich have “moral authority” over the poor. The reasoning is as follows: Success in a competitive world comes from the “moral strengths” of self-discipline and self-reliance – in working hard at developing your abilities, etc. Lack of success, in this worldview, implies not enough self-discipline, ie moral weakness. Thus, the “successful” (ie the rich) are seen as higher in the moral order – as disciplined and hard-working enough to “succeed”.

‘Erosion of values’ & ‘moral purity’

Media hysteria sometimes calms down a little. But it only takes one horrible crime or indication of ‘Un-American’ behaviour (etc) to set it off again. Then we have: “erosion of values”, “tears in the moral fabric”, a “chipping away” at moral “foundations”, “moral decay”, etc. It shouldn’t be surprising that these metaphors for change-as-destruction tend to accompany ‘conservative’ moral viewpoints rather than ‘progressive’ ones.

Associated with moral ‘decay’ is the metaphor of impurity, ie rot, corruption or filth. This extends further, to the metaphor of morality as health. Thus, immoral ideas are described as “sick“, immoral people are seen to have “diseased minds”, etc. These metaphorical frames have the following consequences in terms of how we think:

1. Even minor immorality is seen as a major threat (since introduction of just a tiny amount of “corrupt” substance can taint the whole supply – think of water reservoir or blood supply. This is applied to the abstract moral realm via conceptual metaphor.)

2. Immorality is regarded as “contagious”. Thus, immoral ideas must be avoided or censored, and immoral people must be isolated or removed, forcibly if necessary. Otherwise they’ll “infect” the morally healthy/strong. Does this way of thinking sound familiar? (This framing has taken scaremongering forms in the Brexit and Trump campaigns).

In Philosophy in the Flesh, Johnson & Lakoff point out that with “health” as metaphor for moral well-being, immorality is framed as sickness and disease, with important consequences for public debate:

“One crucial consequence of this metaphor is that immorality, as moral disease, is a plague that, if left unchecked, can spread throughout society, infecting everyone. This requires strong measures of moral hygiene, such as quarantine and strict observance of measures to ensure moral purity. Since diseases can spread through contact, it follows that immoral people must be kept away from moral people, lest they become immoral, too. This logic often underlies guilt-by-association arguments, and it often plays a role in the logic behind urban flight, segregated neighborhoods, and strong sentencing guidelines even for nonviolent offenders.”

Enemies everywhere, everything a threat

There’s a lot to fear from the perspective of ‘strictness morality’: the world’s a dangerous place, there’s immorality and “evil” lurking everywhere – an ever-present threat from the “foreign” and “alien”. And any weakness that you manifest will be punished. Even the good, decent people are competing ruthlessly with you, judging you for any failure.

In a way, this moral framing logically requires that the world is seen as essentially dangerous. Remove this premise and strictness morality ‘collapses’, since the precedence given (in this scheme) to moral strength, self-discipline and authority (over compassion, fairness, happiness, etc) would no longer make sense.

Rightwing media (tabloid newspapers, Fox News, etc) appear to have the function of reinforcing the fearful premise with daily scaremongering – presumably because it’s more profitable than less dramatic “news”. But this repeated stimulation of our fears affects us at a synaptic level. The fear/alarm framing receives continual reinforcement, triggering the ‘strict father’ worldview, making the model more active, more dominant in our brains.

Update (23/1/2017) – see George Lakoff’s comments on Trump’s inaugural speech. Lakoff says “Trump is a textbook example of Strict Father Morality”, but he also gives some clues on Trump’s weaknesses and how to defeat him (for example, Trump is already a “betrayer of trust” – seen as a big sin in strict father morality).

Facts, frames & “post-truth” politics

Some pointers on how frames fit into the debate about “post-truth”, “post-factual” politics, etc.

Some pointers on how frames fit into the debate about “post-truth”, “post-factual” politics, etc.

Frames vs “facts”

We think and reason using frames and metaphors. The consequence is that arguing simply in terms of facts—how many people have no health insurance, how many degrees Earth has warmed in the last decade, how long it’s been since the last raise in the minimum wage—will likely fall on deaf ears. That’s not to say the facts aren’t important. They are extremely important. But they make sense only given a context. (George Lakoff, Thinking Points; my bold emphasis)

Cognitive science tells us that when facts contradict a person’s worldview (their conceptual “framing” of various issues), the facts will probably be ignored and the frames/worldview kept. Knowing that frames typically trump facts doesn’t devalue facts. The knowledge just makes us more aware of what’s going on.

When a person’s conceptual frames don’t mesh well with evidential “reality”, the evidence that doesn’t fit the frame will likely be ignored, overlooked or dismissed. This way of “thinking” differs fundamentally from the classical view of “reason” as applied empirically (eg in scientific method) – in which factual evidence is allowed to challenge, refute and ultimately transform our beliefs about the world.

The lesson from this is that publicising the facts about any issue may not be sufficient to change people’s minds. And no political viewpoint has a monopoly on “objectivity”. Everyone tends to ignore or dismiss the facts which are inconvenient to their worldviews. And everyone tends to find an abundance of “evidence” or “proof” which supports their worldviews. These processes occur because of the way our brains conceptualise with metaphors and frames – resulting in the creation of our personal reality-tunnels, to which we become “attached” (in a physical sense, neurologically).

What can we do about this? We can attempt to become more aware of the process, and thereby make allowances for it – both in our own thinking, and in “reading” the messages we’re subjected to on a daily basis from the mass media.

“News” as story – not facts

No “newsworthy” event (or non-event) has “meaning” without a conceptual frame. We need frames to make sense of anything. As Lakoff et al point out, we don’t think in terms of neutral “facts” – our thoughts aren’t strung-together facts. We require frames to provide “meaning” to facts. Journalists instinctively know this; much of the “news” is presented as narrative frames – taking the form of a story (often with simplistic attribution of causes, heroes and villains, crisis, drama, etc).

How we tend to frame events will depend on our worldviews, our hierarchies of values, etc. Inevitably this will bring into play the “deep” moral frame structures in our psyches. When we read a newspaper story, however, a frame has already been selected for us in advance. If it’s a common news frame (ie one reinforced through repetition over many years), it may seem entirely normal, appropriate and “true” with respect to the “hard facts” (if any) reported. But at the same time it may induce a “tunneling” – or cognitive blinkering – effect, in which crucial “aspects” of the newsworthy event are excluded from our consciousness.

Example frame: “corporation”

This occurs not just with news “events”, but with political and social institutions and abstractions – and indeed any players, roles, entities, etc, involved in the news story. Consider, for example, the notion of a corporation or big firm. It’s an entity that features often in stories on jobs, in which the frame is perhaps “job creation” or “job loss”, etc. The corporation is the creator of jobs, the “engine of productivity”, etc, within that frame.

Now consider the frame favoured by, say, Noam Chomsky: corporations as unaccountable private tyrannies. Both of these frames (corporations as job-creators and corporations as private tyrannies) might be more or less “supported by the facts” – they’re both “true” in that sense. But, of course, they evoke (or invoke) two very different sets of ideas in our minds regarding the reality or “meaning” of corporations.

The way the “news” is often framed, through repetition, means that one set of “meanings” takes prominence over others. This isn’t “bias” in the usual, narrow sense in which media critics use that term. Neither is it primarily about battles between different sets of opposing “facts”. It’s more fundamental than that, and requires that we understand the new cognitive fields of frame semantics, conceptual metaphor and moral-values systems.

Media metaphors

Political frames are communicated by the seemingly everyday language of newspaper headlines and editorial copy. Metaphors activate (in our brains) the frames to which they belong, and this mostly occurs without us noticing.

Media metaphors structure our experience of “the news” and “public mood”, etc – but not just in the sense of “spin” or “propaganda”. Conceptual metaphor isn’t something that’s extraneous to “straightforward factual thinking”. Rather, it’s central to thought – without such metaphors, we couldn’t reason about complex social issues at all.

Newspaper headlines often use metaphors of direct causation to frame complex social issues. All such metaphors have their own logic, which is transferred from the physical realm of force to the more abstract social realms of institutions, politics, beliefs, etc. The effect is inescapably “reductive”, but not necessarily illegitimate (some metaphors – and their imported logics – are more appropriate than others). Here are some examples of such metaphorical causal expressions:

- Public generosity hit by immigrant wave

- 72% believe Iraq on path to democracy

- Obama’s leadership brought the country out of despair

- Majority fear Vietnam will fall to communism

Each of the causal logics here is different – for example, the notion that one country “falls” to communism, while another takes the right “path” (to democracy). Of “falling to communism”, Lakoff & Johnson remark (Philosophy in the Flesh, p172) that the ‘domino effect’ theory was used to justify going to war with Vietnam: when one country “falls”, the next will, and the next – unless force (military might) is applied to stop the “falling”. The metaphor of taking a “path” has very different political entailments. A nation might not even resemble a democracy, but if it chooses the “right path”, it “deserves” US military and economic “aid”, to help overcome any obstacles put in its “way”. (Incidentally, many rightwing ideologues regard any “move” towards “free market” economics as taking the “path” to democracy).

The discovery of frames requires a reevaluation of rationalism, a 350-year-old theory of mind that arose during the Enlightenment. We say this with great admiration for the rationalist tradition. It is rationalism, after all, that provided the foundation for our democratic system. […] But rationalism also comes with several false theories of mind. […]

If you believed in rationalism, you would believe that the facts will set you free, that you just need to give people hard information, independent of any framing, and they will reason their way to the right conclusion. We know this is false, that if the facts don’t fit the frames people have, they will keep the frames (which are, after all, physically in their brains) and ignore, forget, or explain away the facts. (George Lakoff, Thinking Points; my bold emphasis)

UPDATES – Overweening Generalist, ‘Degrowth’, RAW, ‘ego depletion’

I’ve combined a couple of “Updates” posts into one here (as the menu was getting a bit messy).

April 18, 2016:-

1. A new piece from one of my favourite websites, the Overweening Generalist blog, which comments on (among other things) an article I wrote about Robert Anton Wilson and George Lakoff (the longer version of the piece published at Disinfo.com).

It contains some brilliant observations and comments – give it a read: George Lakoff and Robert Anton Wilson and the Primacy of Metaphors (Overweening Generalist)

2. I’ve just seen a new paper from Ecological Economics journal (April 2016), from Stefan Drews and Miklós Antal, titled Degrowth: A “missile word” that backfires? It discusses the “degrowth” campaign/slogan from the perspective of cognitive framing, and references a piece that I wrote on the subject. Full text (PDF) here.

April 8, 2016:-

1. My Disinfo.com article about Robert Anton Wilson was originally much longer than the one I submitted to Disinfo. I’ve posted the original, longer piece (over 2,000 words) right here, along with a much bigger image.

2. I’ve previously written about “ego depletion”, a seemingly well-supported phenomenon in psychological studies (Daniel Kahnemen cites the work in his book, Thinking, Fast and Slow). But as this fascinating new article claims, “An influential psychological theory, borne out in hundreds of experiments, may have just been debunked”.

Nassim Taleb commented on Twitter, ‘Fortune tellers are about 50% right. With psychology it seems worse. Hypocritical to call this “science”‘. That seems an interesting debate in its own right. Input/feedback welcome, as always…

Rather than leave you hanging on that question of whether psychology should be considered science, I’ll give you a few links with some quality input:

- A discussion on BBC Radio 3 between Rupert Read and Keith Laws, which tackles this question. Starts 35 minutes in, and I found it fascinating (the debate continued on Twitter, and Rupert made some interesting comments on that debate here).

- Since this debate brings up figures such as Popper and Kuhn, why not invite the whole party, to get an idea of what’s going on – Feyerabend, Lakatos and others are here at this Overweening Generalist piece. (It even includes a reference to Robert Anton Wilson, making it more topical with regard to my other update, above. Not bad, considering.)

RAW: new article for Disinfo

22 March 2016 – I’ve written an article for disinfo.com about the resurgence of interest in Robert Anton Wilson’s ideas. As well as looking at a couple of new RAW-related books, it continues the theme I’ve already written (briefly) about – on the harmoniousness between RAW’s mutiple-model neurosemantics and Lakoff’s Frame Semantics.

I shortened it from my original 2,000 words to 1,200 (which is Disinfo’s preferred maximum article length), but I’m pleased with the result, and think you’ll enjoy it. (The accompanying photo is of my Robert Anton Wilson “stash”). Here is the article:

http://disinfo.com/2016/03/raw-resurgence/ (Link is now dead – see below*)

*Web Archive copy of above disinfo.com page here.

*UPDATE (Aug 2019): Disinfo.com seems to have closed down, so the original link above is now dead. There’s a longer version of the article here.

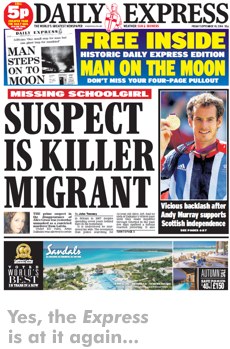

Tabloid stereotypes – typifying classes by worst-cases

Sept 19, 2014 –Today’s Daily Express headline is a particularly nasty example of an irresponsible tabloid practice. Most people would probably (and rightly) think of it as demonisation of a class of people – by constant publication of nightmare cases whose attributes are in no way typical of the class (“migrants”, “benefit claimants”, etc) assigned by the newspaper.

Sept 19, 2014 –Today’s Daily Express headline is a particularly nasty example of an irresponsible tabloid practice. Most people would probably (and rightly) think of it as demonisation of a class of people – by constant publication of nightmare cases whose attributes are in no way typical of the class (“migrants”, “benefit claimants”, etc) assigned by the newspaper.

Apologists for the Express might argue that the headline is factually correct (assuming the details have been reported correctly). But the point is how “facts” and “news” about sensational single cases can be framed in a way that distorts probability judgments, warps logic and incites hatred/fear regarding the class of people referred to.

Prototype Theory: distorting our judgments

Prototype Theory, in cognitive science, looks at the internal structure of categories/classes, and how single class members can stand for the class itself. It offers a useful explanation of what’s going on here (ie how the Express is fucking with our heads, precisely).

Our minds create various kinds of prototype for a given category/class. For example, a typical case, an ideal case and a nightmare case. We tend to use the “typical case” prototype in our inferences about what we consider “normal” (eg statistically, probabilistically) for a category, or class, of people.

Problems arise with something called a “salient exemplar” (a well-known case that stands out for us, for various reasons – including sensationalist media coverage. The tabloids are full of them). The salient exemplar tends to distort our probability judgments about a given class of people if it’s conflated with, or affects our perceptions of, the “typical case”. This can happen quickly, and without much conscious awareness – eg as a result of the repeated media coverage (of the salient exemplar), we have “reflex” associations and responses to the “migrant” frame.

The Express (and it’s not just the Express) knows it would get into trouble with a “KILLER BLACK”, “KILLER GAY” or “KILLER JEW” headline. But it knows it can get away with “KILLER MIGRANT”, just as it knows that it can get away with portraying the class of “welfare recipients” in terms of the “vile” “cheat” salient exemplar. The examples are endless – see my Curious repeating headlines in the Daily Express for a selection).

It isn’t new, of course. Lakoff (in The Political Mind) discusses the uproar that started in 1976, when Ronald Reagan referred to a “Welfare Queen” who had supposedly received $150,000 in government handouts and was driving a “Welfare Cadillac”. As it turned out, nobody could find this person – it appeared to be a made-up stereotype. As Lakoff puts it, “Reagan made the invented Welfare Queen into a salient exemplar, and used the example in discourse as if it were the typical case.” (The Political Mind, p160)

Misleading Vividness fallacy

I mentioned, above, how sensationalist tabloid framing warps logic regarding classes of people. There’s a fallacy in logic known as “Misleading Vividness“, eg the belief that the occurrence of a particularly vivid event (eg a terrorist bombing) makes such events more likely, despite statistical evidence indicating otherwise. Misleading Vividness has strong psychological effects because of a cognitive heuristic called the availability heuristic. There’s a lot of material already available on cognitive heuristics (as a result of the popularity of the work of Daniel Kahneman and others). I think it would be a fruitful area of research to combine this field with that studied by Lakoff et al, particularly with emphasis on media coverage and its effects. In the words of Nassim Taleb (quoted by New Scientist some time ago), media coverage is “destroying our probabilistic mapping of the world”.

Framing vs “Orwellian language”

April 24, 2014 – Orwell’s fiction ‘memes’ – Newspeak, doublethink, Big Brother, etc – still sound resonant to me, but his famous essay, Politics and the English Language, seems outdated (and wrong) in important respects. Of course, you can’t blame Orwell for not knowing what cognitive science and neuroscience would discover after his death – most living people still have no idea how those fields have changed our understanding of language and the mind over the last 35 years.

April 24, 2014 – Orwell’s fiction ‘memes’ – Newspeak, doublethink, Big Brother, etc – still sound resonant to me, but his famous essay, Politics and the English Language, seems outdated (and wrong) in important respects. Of course, you can’t blame Orwell for not knowing what cognitive science and neuroscience would discover after his death – most living people still have no idea how those fields have changed our understanding of language and the mind over the last 35 years.

Orwell’s essay is premised on a view of reason that comes from the Enlightenment. It’s a widespread view that’s “reflexively” still promoted not just by the “liberal-left” media and commentariat, but also by the Chomskyan “radical left”. And, as George Lakoff and others have been at pains to point out, it’s a view of reason which now seems totally wrong – given what the cognitive/neuroscience findings tell us.

I’ll return to Orwell in a moment, but, first: Why does the Enlightenment view of reason seem wrong? Well, it’s an 18th-Century outlook which takes reason to be conscious, universal, logical, literal (ie fits the world directly), unemotional, disembodied and interest-based (Enlightenment rationalism assumes that everyone is rational and that rationality serves self-interest). It follows from this viewpoint that you only need to tell people the facts in clear language, and they’ll reason to the right, true conclusions. As Lakoff puts it, “The cognitive and brain sciences have shown this is false… it’s false in every single detail.”

From the discoveries promoted by the cog/neuro-scientists, we find that reason is mostly unconscious (around 98% unconscious, apparently). We don’t know our own system of concepts. Much of what we regard as conceptual inference (or “logic”) arises, unconsciously, from basic metaphors whose source is the sensory and motor activities of our nervous systems. Also, rationality requires emotion, which itself can be unconscious. We always think using frames, and every word is understood in relation to a cognitive frame. The neural basis of reasoning is not literal or logical computation; it entails frames, metaphors, narratives and images.

So, of course: we have different worldviews – not universal reason. It seems obvious, but needs repeating: We don’t all think the same – only a part of our conceptual systems can be considered universal. So-called “conservatives” and “progressives” don’t see the world in the same way; they have different forms of reason on moral issues. But they both see themselves as right, in a moral sense (with perhaps a few “amoral” exceptions).

Many on the left apparently find this difficult to comprehend. Given the Enlightenment premise of universal reason, they think everyone should be able to reason to the conclusion that conservative (or “Capitalist”) positions are immoral. All that’s needed, they believe, is to tell people the unadorned facts, the “truth”. And if people won’t reason to the correct moral conclusions after being presented with the facts, that must imply they are either immoral or “brainwashed”, hopelessly confused or “pathological”.

Few people have exclusively “conservative” or exclusively “progressive” views on everything. We all seem to have both modes of moral reasoning in our brains. (The words “conservative” and “progressive” may seem somewhat arbitrary, inadequate categories, but the distinct “moral” cognitive systems which they point to seem far from arbitrary – see Lakoff’s Moral Politics). You can think “progressively” in one subject area and “conservatively” in others, and vice-versa. And you might not be aware that you’re switching back and forth. It’s called “mutual inhibition” – where two structures in the brain neurally inhibit each other. If one is active, it will deactivate the other, and vice-versa. To give a crude example, constant activation of “conservative” framing on, say, the issue of welfare (eg the “benefit cheats” frame) will tend to inhibit the more “progressive” mode of thought in that whole subject area.

It’s a fairly common experience for me to chat with someone who seems rational, decent, friendly, etc; and then they suddenly come out with what I regard as a “shocking” rightwing view – something straight out of, say, UKIP – a view which they obviously believe in sincerely. This shouldn’t be surprising given the statistical popularity of the Daily Mail, Express, UKIP, etc, but it always conveys to me – in a ‘visceral’ way – the inadequacy of certain left/liberal assumptions about how reasonable, “ordinary” (as opposed to “elite”) people are “supposed” to think.

Orwell’s ‘Politics and the English Language’

To return to Orwell and his essay – he writes that certain misuses of language promote a nefarious status quo in politics. For example, he argues that “pretentious diction” is used to “dignify the sordid process of international politics”. He says that “meaningless words” such as “democracy” and “patriotic” are often used in a consciously dishonest way with “intent to deceive”. The business of political writing is one of “swindles and perversions”; it is the “debasement of language”. For Orwell, it is “broadly true that political writing is bad writing”, and political language “has to consist largely of euphemism, question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness”.

Much of this still seems valid (nearly 70 years after Orwell wrote it) – and some of the examples of official gibberish that Orwell cites are as amusing as what you might see in today’s political/bureaucratic gobbledygook. But it’s the cure that Orwell proposes which embodies the Enlightenment fallacy (and which Lakoff, for example, has described as “naive and dangerous”):

What is above all needed is to let the meaning choose the word, and not the other way around. In prose, the worst thing one can do with words is surrender to them… Probably it is better to put off using words as long as possible and get one’s meaning as clear as one can through pictures and sensations. Afterward one can choose — not simply accept — the phrases that will best cover the meaning… (George Orwell, Politics and the English Language)

Orwell then provides a list of simple rules to help in removing the “humbug and vagueness” from political language (such as: “Never use a long word where a short one will do”). He states that “one ought to recognize that the present political chaos is connected with the decay of language”, and that, “If you simplify your English, you are freed from the worst follies of [political] orthodoxy”.

What are the fallacies here? Well, most obvious is the notion that political propaganda can be resisted with language which simply fits the right words to true meanings, without concealing or dressing anything up. Anyone who has studied effective political propaganda will tell you that it already does precisely that. The most convincing, persuasive propaganda, rhetoric or political speech seems to be that which strikes the reader or listener as plain-speaking “truth”. In many ways, the right seems to have mastered this art.

The fallacy comes from the Enlightenment notion that because people are rational, you only need to tell them the “plain facts” for them to reason to the truth. We know, however, that facts are interpreted according to frames. Every fact, and every word, is understood in relation to a frame. To borrow an example from my previous article, you can state that “corporations are job creators”, and you can state that “corporations are unaccountable private tyrannies”. Two different frames, neither of which consists of “debasement” of language or factual deception. Rather, it’s a question of activating different worldviews.

Orwell’s notion of letting “the meaning choose the word” seems to imply that our “meanings” exist independently of the semantic grids and cognitive-conceptual systems in our brains. Again, this comes from the Enlightenment fallacy – that there’s a disembodied reason or “meaning” which is literal (or “truth”), and which we can fit the right words to, in order to convey literal truth. It seems more accurate to say that we need conceptual frames to make sense of anything – or, as the cognitive scientists tell us, we require frames, prototypes, metaphors, narratives and emotions to provide “meaning”.

A lot of political/media rhetoric does seem to conform to Orwell’s diagnosis, and its language can probably be clarified by his rules and recommendations. But it’s not this “vague”, “pretentious”, “deceptive” type of rhetoric or propaganda that worries me most. What worries me is the rightwing message-machine’s success (if we believe the polls/surveys) in communicating “plain truths” to millions by framing issues in ways which resonate with people’s fears and insecurities – and which tend to activate the more “intolerant”, or “strict-authoritarian” aspects of cognition, en masse.

Lakoff in Guardian

Feb 5, 2014 – Just a brief post to: a) point to a smart Guardian piece on George Lakoff’s ideas, and b) express my frustration (ranty prose ahead) at the level of ignorance/idiocy on the topic of framing that I see in feedback on newspaper comments sections, Twitter etc.

Feb 5, 2014 – Just a brief post to: a) point to a smart Guardian piece on George Lakoff’s ideas, and b) express my frustration (ranty prose ahead) at the level of ignorance/idiocy on the topic of framing that I see in feedback on newspaper comments sections, Twitter etc.

I’ve found Twitter useful for searches. For example, a search on “lakoff” brought up tweets linking to Zoe Williams’s new Guardian article (well worth taking the time to read). Unfortunately, the same search brings up an assortment of not-so-knowledgeable reactions to the article, and to Lakoff’s ideas in general.

It’s the same with the “post a response” sections underneath online newspaper articles. Tom Hodgkinson (editor of The Idler) recently put it this way:

“At the foot of the article sat a collection of ‘comments’ by the usual collection of morons. Anyone who believes in the democratization of journalism should check out the dimwits who gather ‘below the line’. The Telegraph ones seemed even more big-headed and stupid than the Guardian ones, if that’s possible.” *

Zoe Williams’s article states that Lakoff prescribes “the abandonment of argument by evidence in favour of argument by moral cause”, which is understandable within the context of Lakoff’s cognitive-linguistics work on how we think (eg in political frames). But to someone who isn’t familiar with Lakoff’s academic books, and the emphasis he places on empirical research, the notion of abandoning “argument by evidence” (and the notion that “facts” “weaken” political beliefs) probably confirms their ignorance-derived suspicions that framing subverts “reason” in a bad way. Indeed, the first response to Williams’s article was this:

Interestingly, the Guardian article attracted less than 50 comments – low compared to the number Zoe William’s articles usually get. That’s probably because it was hidden away in the ‘Philosophy’ section of the Guardian site, rather than in the more-publicised ‘Comment is Free’ area – a strange decision by whoever was responsible (it’s happened before with Lakoff-themed pieces) given that the article seems more topical and comment-worthy than much of the frivolous space-filler published in CiF. Williams’s article was also posted (pirated? stolen?) at the “independent” media sites, AlterNet and The Raw Story, where, in both cases, it attracted several hundred comments (many of them as stupid and/or ignorant as the ones you get at online corporate media). I hope those sites pay Zoe something for her work, or at least asked her permission to publish.

Moving back to Twitter. One of my “lakoff” searches brought up the following:

It turns out that both of these Tweeters write for the Guardian and New Left Project (and one of them follows me on Twitter). So I can’t quickly dismiss such remarks as ignorant Twitterish. But I find it a tad frustrating: you don’t have to read the complete Lakoff oeuvre to see that he doesn’t “ignore” those things mentioned in the tweet. Probably just one of his books is sufficient to show that. To dig deeper, there’s a rich treatment of the “libertarian-authoritarian axis” in his work on moral politics. The academic work on conceptual metaphor, prototype and narrative will likely give you more new insights into the “difference between sales pitch and product” than you’ll find in 99.9% of political commentary (including the “radical left” variety).

As for “ignoring” “big money”, the irony is that Lakoff’s political books (Whose Freedom, Don’t Think of an Elephant, etc) seem motivated by his concern precisely at the way “big money” – via the giant, massively-funded rightwing messaging machine, acting through the mass media – has managed to shape our thinking for decades, at the level of what we think of as “common sense”. This is a constantly recurring theme in Lakoff’s books, together with his treatment of “free market” ideology and what he calls the ‘Economic Liberty Myth’.

Note: If you were perplexed by the notion of making evidence and facts less prominent in political argument, I’d recommend the following passages from Lakoff’s Thinking Points, to give a flavour of what he is saying:

We think and reason using frames and metaphors. The consequence is that arguing simply in terms of facts—how many people have no health insurance, how many degrees Earth has warmed in the last decade, how long it’s been since the last raise in the minimum wage—will likely fall on deaf ears. That’s not to say the facts aren’t important. They are extremely important. But they make sense only given a context. […]

We were not brought up to think in terms of frames and metaphors and moral worldviews. We were brought up to believe that there is only one common sense and that it is the same for everyone. Not true. Our common sense is determined by the frames we unconsciously acquire […] The discovery of frames requires a reevaluation of rationalism, a 350-year-old theory of mind that arose during the Enlightenment. We say this with great admiration for the rationalist tradition. It is rationalism, after all, that provided the foundation for our democratic system. […] But rationalism also comes with several false theories of mind.

We know that we think using mechanisms like frames and metaphors. Yet rationalism claims that all thought is literal, that it can directly fit the world; this rules out any effects of framing, metaphors, and worldviews. We know that people with different worldviews think differently and may reach completely different conclusions given the same facts. But rationalism claims that we all have the same universal reason. Some aspects of reason are universal, but many others are not—they differ from person to person based on their worldview and deep frames.

We know that people reason using the logic of frames and metaphors, which falls outside of classical logic. But rationalism assumes that thought is logical and fits classical logic.

If you believed in rationalism, you would believe that the facts will set you free, that you just need to give people hard information, independent of any framing, and they will reason their way to the right conclusion. We know this is false, that if the facts don’t fit the frames people have, they will keep the frames (which are, after all, physically in their brains) and ignore, forget, or explain away the facts.

If you were a rationalist policy maker, you would believe that frames, metaphors, and moral worldviews played no role in characterizing problems or solutions to problems. You would believe that all problems and solutions were objective and in no way worldview dependent. You would believe that solutions were rational, and that the tools to be used in arriving at them included classical logic, probability theory, game theory, cost-benefit analysis, and other aspects of the theory of rational action.

Rationalism pervades the progressive world. It is one of the reasons progressives have lately been losing to conservatives. Rationalist-based political campaigns miss the symbolic, metaphorical, moral, emotional, and frame-based aspects of political campaigns.

* From Hodgkinson’s Register, mailed on 29/10/13.

Both “growth” and “the economy” are what Lakoff calls ontological metaphors. They enable us to think about unthinkably multifarious phenomena (eg all the things “of value” that people do) in terms of “discrete entities or substances of a uniform kind”. This isn’t about “mere language”, but about how people think. The “price we pay” is to be stuck with crude, reductive (eg two-valued) logics, eg growth/no-growth. And it doesn’t help much to change the definition of “Gross Domestic Product” (GDP), or to divide “the economy” into sectors – it simply applies the same binary logic to slightly different, or smaller, entities.

Both “growth” and “the economy” are what Lakoff calls ontological metaphors. They enable us to think about unthinkably multifarious phenomena (eg all the things “of value” that people do) in terms of “discrete entities or substances of a uniform kind”. This isn’t about “mere language”, but about how people think. The “price we pay” is to be stuck with crude, reductive (eg two-valued) logics, eg growth/no-growth. And it doesn’t help much to change the definition of “Gross Domestic Product” (GDP), or to divide “the economy” into sectors – it simply applies the same binary logic to slightly different, or smaller, entities. Another aspect of market ideology reinforced by the “growth” frame is the heroic individualist entrepreneur fairy tale. “Growth” as a personal or individual-business metaphor seems unproblematic, but when we reflexively conceive of “the economy” as an object with an attribute of “growth”, the entrepreneur idea extends to it “naturally” because of the “good growth” frame. This is the myth that practically all wealth/”growth” derives from entrepreneurial enterprise, which is heroically fighting against “unnatural” interference to growth (eg from governments, “do-gooders”, Green activists, etc).

Another aspect of market ideology reinforced by the “growth” frame is the heroic individualist entrepreneur fairy tale. “Growth” as a personal or individual-business metaphor seems unproblematic, but when we reflexively conceive of “the economy” as an object with an attribute of “growth”, the entrepreneur idea extends to it “naturally” because of the “good growth” frame. This is the myth that practically all wealth/”growth” derives from entrepreneurial enterprise, which is heroically fighting against “unnatural” interference to growth (eg from governments, “do-gooders”, Green activists, etc).